Okay, kids — before we get back to the story of how “Beastly Kingdom” ended up on Disney Animal Kingdom’s (DAK) endangered species list — you need to understand what the Mouse’s original expectations were for its fourth Walt Disney World (WDW) theme park. Here’s what Disney CEO Michael Eisner had hoped would happen when DAK opened on April 1998:

Attendance levels would go through the roof at the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios, as a record number of visitors rushed down to Florida to check out WDW’s fourth theme park.

Guests who had previously stayed on property at Walt Disney World hotels for four days would now book five day vacation packages — just to be sure that they didn’t miss any of the new shows and attractions that had recently been added to the resort.

All this extra guest traffic would result in increased revenues for WDW’s hotels, shops and restaurants — which would have an immediate positive impact on the Walt Disney Company’s bottom line.

Eisner and his staff would bask in the glow of the unparalleled success of Disney’s Animal Kingdom for a moment … then get right back to work, brain-storming ideas for WDW’s fifth theme park.

That what Uncle Michael had hoped would happen, anyway. Reality proved to be infinitely harsher.

In spite of the Mouse’s rosy projections, Disney’s Animal Kingdom — in its first year of operation:

Actually drove down attendance levels at the other three WDW theme parks: In 1998, 8% fewer guests visited the Magic Kingdom; 9% fewer went to the Disney-MGM Studios; while Epcot’s attendance levels dipped a startling 11%.

What happened? In a word — cannibalism.

“Cannibalism” is the term Disney Company executives use to describe what happens when a brand new theme park opens and begins eating into the attendance levels of the older, more established parks at the same resort.

In 1982, when Epcot opened, that park initially cut significantly into the number of guests that annually visited the Magic Kingdom. However — over time — attendance levels at Magic Kingdom bounced back to what they once were after the newness of Epcot had worn off. Meanwhile, Epcot Center began drawing guests all on its own to WDW. In the end, it all worked out just fine.

A similar thing happened in May 1989, when the Disney-MGM Studio theme park threw open its gates. For almost a year, attendance levels at the Magic Kingdom and Epcot slumped while guests opted to go to the new WDW theme park rather than visiting their old favorites. But — once again, over time — the situation sorted itself out. Attendance levels at the older WDW parks slowly rose back up to where they once were, as the Disney-MGM Studios began luring millions of new tourists to come see Disney’s Florida resort.

The Mouse had been anticipating that — when Disney’s Animal Kingdom opened — that it too would initially bleed guests away from the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios. That’s why Eisner had had the Imagineers add new attractions and/or complete major rehabs to each of the older WDW parks in the 18 months prior to DAK’s opening.

This was Uncle Michael’s brilliant scheme. He honestly believed that — if the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios each had new rides and shows for visitors to see — guests who had come down to WDW just to see Disney’s Animal Kingdom during its first year of operation would still end up of staying on property an extra day or so just to check out all the new stuff at the other parks.

On paper, that really did seem like a brilliant plan. Too bad reality got in the way.

What happened to ruin Eisner’s plan? For starters, Epcot’s heavily hyped new thrill ride — GM Test Track — was beset with horrible technical problems and ended up opening a full 18 months behind schedule. So that park really had nothing new to offer to returning WDW guests the year DAK opened.

Over at the Disney-MGM Studios, a much anticipated addition to the park — “David Copperfield’s Magic Underground” restaurant — never made it off the drawing board because the magician’s outside financing for the project disappeared. It would now be months after DAK’s opening before the studio theme park’s next big attraction — an East Coast version of Disneyland’s “Fantasmic” — would be ready to start entertaining WDW visitors.

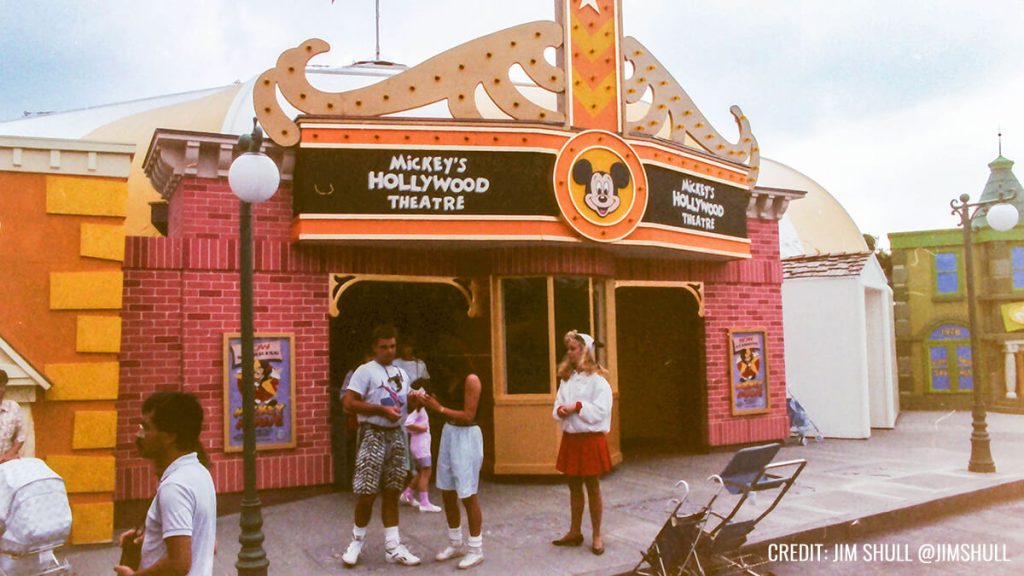

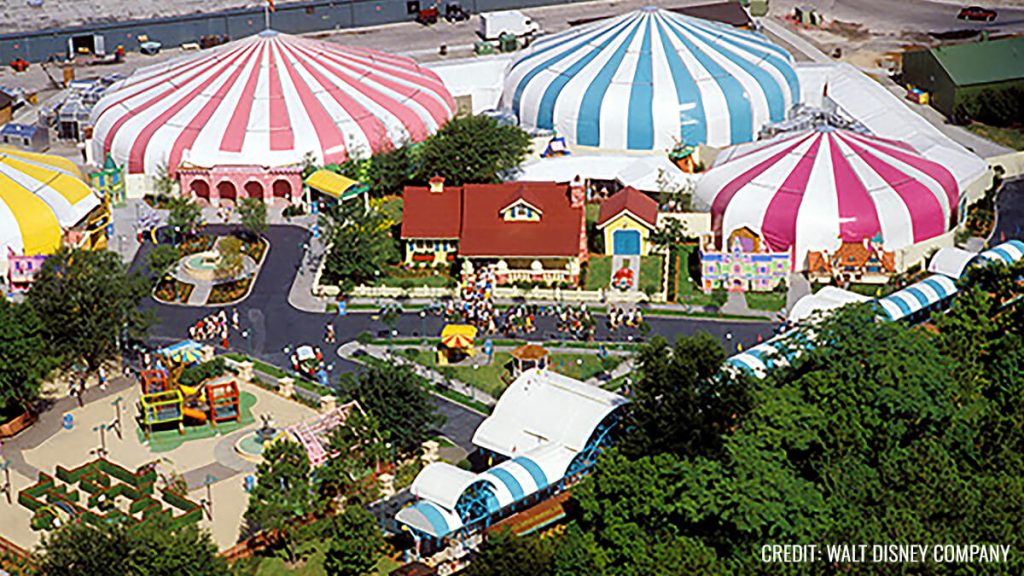

As for the Magic Kingdom … truth be told, very little thought was put into to adding new shows and attractions to WDW’s first theme park. The Magic Kingdom had always been the favorite with Disney World visitors. Eisner and WDI felt that — what with the recent “Mickey’s Toontown Faire” redo as well as the 25th anniversary parade that was still running daily at the park — there was still plenty of semi-new stuff to entice people into making a return trip to the Magic Kingdom.

So — given all the money the Walt Disney Company had pumped into the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios to counter-act the effects of DAK’s opening — Eisner had anticipated that the attendance levels at WDW’s older parks would only dip by 5% in 1998. He was said to be furious when — almost across the board — attendance fell by almost twice that amount at all three of the other WDW theme parks.

This news immediately put WDW’s management team into crisis mode. The big boys in Burbank wanted attendance levels at each of the older WDW parks driven back up immediately. The managers of the Magic Kingdom, Epcot, and the Disney-MGM Studios reminded Eisner and Company that — in order to do that — they’d need money fast for new shows, parades and attractions. Eisner immediately agreed to free up some funds for the Florida park.

And where did Eisner get the money to create these new WDW shows? You guessed it, kids. He snagged the funds that had been previously earmarked for expansion of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Specifically, the money that would have been set aside for construction of “Beastly Kingdom.”

Again, Rohde and his Imagineers began complaining about the short-sightedness of Disney management’s fiscal planning. With that money gone, it would now be five years or more before there’d be any money in the budget to create any new significant attractions for DAK.

WDW managers admitted that this was true. But — given all the problems that Disney’s Animal Kingdom was having during its initial year of operation — it didn’t seem too wise right now to complain about the park’s future. Unless these problems got resolved quickly, it didn’t look like DAK would have much of a future.

What sort of problems was Disney’s Animal Kingdom having back then? You name it, the park was having problems with it. For example: Due to the twisty, turny nature of the park’s walkways as well as all the lush vegetation, guests were constantly getting lost as they walked through the park. Disney had to spend thousands on new, bigger signage for the theme park to help guests find their way around the place.

Then there was all the troubles with DAK’s shops and restaurants. Particularly during the first eight months Disney’s Animal Kingdom was open (when only the African safari adventure was up and running), the Mouse had an awful time getting guests to stay inside the theme park past 4 p.m.

What was the problem? Due to the horrible heat in Florida, most of the animals along the African safari route would go lie down in the shade — disappearing entirely from view — by about 10 a.m. each morning. Once DAK management learned that its African menagerie had begun dropping from sight most days before noon, it quickly put the word out to WDW’s hotels to encourage their guests to visit DAK as early in the day as possible.

This resulted in a completely unworkable traffic flow situation at DAK. By 7:30 a.m. most mornings during that first summer of operation, the park would already be full. By 8 a.m., there’d be a two hour long line in the queue for the African safari ride as well as guests waiting for over an hour to get in to see “It’s Tough to Be a Bug.” Given that so few of Disney Animal Kingdom’s restaurants had been designed to serve breakfast, there were never enough places open at that hour to handle all those sleepy, cranky people looking for food. That first summer at DAK was a complete disaster.

But — as bad as the early morning hours at DAK were — the late afternoon was even worse. Why for? Because the crowds — having blown through Disney’s Animal Kingdom minimal number of shows and attractions in just a few hours — had already left the park for the day. By 4 p.m. most afternoons, you could have fired a cannon down the middle of the street in Safari Village and not have wounded a single soul.

Having the park virtually empty by late afternoon played hell with DAK’s projections for food and merchandise sales. All the managers of the park’s stores and restaurants were begging WDW management for help in turning around their depressed sales. (The folks running the giant “Rainforest Cafe” at the entrance of Disney’s Animal Kingdom were particularly desperate. They had paid big bucks for the right to build this branch of their restaurant chain right outside the entrance to WDW’s newest theme park. But most evenings, barely a third of the cavernous cafe had any guests in it.)

WDW management tried to come up with a solution to DAK’s traffic flow problems. But it quickly became obvious that there’d be no quick fixes for this situation. After all, it wasn’t like Disney could do here what they did at Epcot and the Disney-MGM Studios to keep guests in the park at night. Since the lights in the skies and all the noise was sure to frighten the animals, a nightly fireworks display was out of the question.

There was also some talk of creating a special night-time parade to roll through the streets of Disney’s Animal Kingdom and entertain guests after dark. For a time, WDW management even considered bringing Disneyland’s much maligned “Light Magic” streetacular to Florida to provide after-hours entertainment at DAK.

But Rohde and his team of WDI designers quickly killed any talk about night-time streetaculars at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. They pointed out that the park’s streets and trails were just too tight and narrow to allow even the smallest floats easy passage. The Imagineers reminded WDW management how much trouble DAK’s small day-time parade — “The March of the Art-imals” — was having making its way around the park in broad daylight. Imagine how much trouble a similar parade would have making its way around DAK in the dark.

Rohde’s team insisted that the solution to the traffic flow problems at Disney’s Animal Kingdom was obvious: beef up the parts of the park that didn’t rely on real animals. That meant adding new shows to Dinoland USA as well as finally building Beastly Kingdom. By adding these additional shows and attractions, WDW management would give guests a real reason to stay at DAK after dark — rather than trying to trick visitors into staying with a lame after-hours parade and/or a smallish fireworks display.

Privately, officials in WDW management agreed with the Imagineers that this was the logical, reasonable way to fix Disney’s Animal Kingdom. The trouble was that the folks back in Burbank weren’t acting reasonably or logically right now. Disney Company management had panicked when they had seen the drastic dip in attendance at WDW’s three other theme parks. Now they were running scared.

And Eisner had already okayed WDW management’s decision to grab the money that had been earmarked for DAK expansion and use it for bolstering sagging attendance at the other three WDW theme parks. That meant that Imagineering had next to no money left to fix all the glaring problems at Disney’s Animal Kingdom. More ominously, it now looked like it would be five years — or more — before WDI could afford to add any significant new attractions to DAK.

It was a very depressing time for the Disney’s Animal Kingdom design team. But — again — Rohde told his Imagineers not to lose heart. He told them that DAK — in particular “Beastly Kingdom” — might still be saved yet.

For Joe knew that Seagrams / MCA was spending two billion dollars to expand its Universal Studios Florida theme park complex — which was just down the road from WDW. And the centerpiece to this ambitious expansion project was a brand new theme park: Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure.

Rumors were flying around the theme park community that Seagrams / MCA was spending hundreds of millions of dollars on their new Florida park because they were out to top Disney. Universal wanted “Islands of Adventure” to have such amazing state-of-the-art attractions that this park would top any ride that could be found at Walt Disney World.

Secretly, Rohde and his Imagineers were hoping that Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure would be a huge success. Why for? Because the Walt Disney Company would then be embarrassed that it didn’t have the best rides in Florida anymore. And then maybe the Mouse would get worried that they were starting to lose guests to the new Universal park.

If that happened … well, then Eisner would finally have to open up his wallet then, wouldn’t he? Just as a matter of pride, he’d have to insist that WDI install the greatest rides that they could come up with at each of the WDW parks. For Disney’s Animal Kingdom, that could only mean that the Imagineers would finally get the chance to build “Beastly Kingdom.”

That was how Joe Rohde hoped things would play out, anyway.

Well, in the spring of 1999, Universal Studios’ Islands of Adventure did finally open up. Unfortunately, it was not quite the roaring success Joe had hoped for.

Worse still, some of the attractions to be found in the new park looked awfully familiar …

History

The Evolution and History of Mickey’s ToonTown

Disneyland in Anaheim, California, holds a special place in the hearts of Disney fans worldwide, I mean heck, it’s where the magic began after all. Over the years it’s become a place that people visit in search of memorable experiences. One fan favorite area of the park is Mickey’s Toontown, a unique land that lets guests step right into the colorful, “Toony” world of Disney animation. With the recent reimagining of the land and the introduction of Micky and Minnies Runaway Railway, have you ever wondered how this land came to be?

There is a fascinating backstory of how Mickey’s Toontown came into existence. It’s a tale of strategic vision, the influence of Disney executives, and a commitment to meeting the needs of Disney’s valued guests.

The Beginning: Mickey’s Birthdayland

The story of Mickey’s Toontown starts with Mickey’s Birthdayland at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom. Opened in 1988 to celebrate Mickey Mouse’s 60th birthday, this temporary attraction was met with such overwhelming popularity that it inspired Disney executives to think bigger. The idea was to create a permanent, immersive land where guests could step into the animated world of Mickey Mouse and his friends.

In the early ’90s, Disneyland was in need of a refresh. Michael Eisner, the visionary leader of The Walt Disney Company at the time, had an audacious idea: create a brand-new land in Disneyland that would celebrate Disney characters in a whole new way. This was the birth of Mickey’s Toontown.

Initially, Disney’s creative minds toyed with various concepts, including the idea of crafting a 100-Acre Woods or a land inspired by the Muppets. However, the turning point came when they considered the success of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” This film’s popularity and the desire to capitalize on contemporary trends set the stage for Toontown’s creation.

From Concept to Reality: The Birth of Toontown

In 1993, Mickey’s Toontown opened its gates at Disneyland, marking the first time in Disney Park history where guests could experience a fully realized, three-dimensional world of animation. This new land was not just a collection of attractions but a living, breathing community where Disney characters “lived,” worked, and played.

Building Challenges: Innovative Solutions

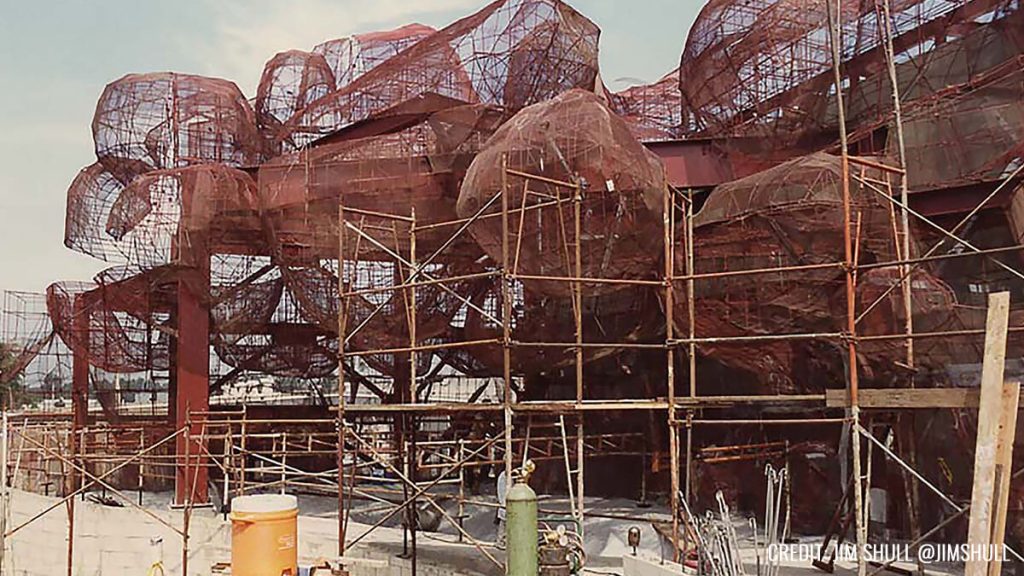

The design of Mickey’s Toontown broke new ground in theme park aesthetics. Imagineers were tasked with bringing the two-dimensional world of cartoons into a three-dimensional space. This led to the creation of over 2000 custom-built props and structures that embodied the ‘squash and stretch’ principle of animation, giving Toontown its distinctiveness.

And then there was also the challenge of hiding the Team Disney Anaheim building, which bore a striking resemblance to a giant hotdog. The Imagineers had to think creatively, using balloon tests and imaginative landscaping to seamlessly integrate Toontown into the larger park.

Key Attractions: Bringing Animation to Life

Mickey’s Toontown featured several groundbreaking attractions. “Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin,” inspired by the movie “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” became a staple of Toontown, offering an innovative ride experience. Gadget’s Go-Coaster, though initially conceived as a Rescue Rangers-themed ride, became a hit with younger visitors, proving that innovative design could create memorable experiences for all ages.

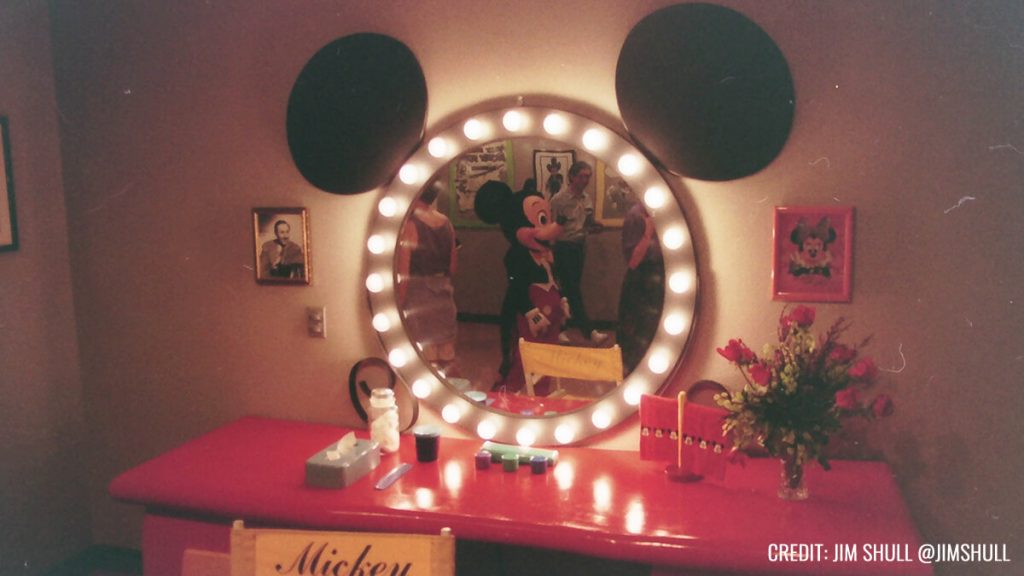

Another crown jewel of Toontown is Mickey’s House, a walkthrough attraction that allowed guests to explore the home of Mickey Mouse himself. This attraction was more than just a house; it was a carefully crafted piece of Disney lore. The house was designed in the American Craftsman style, reflecting the era when Mickey would have theoretically purchased his first home in Hollywood. The attention to detail was meticulous, with over 2000 hand-crafted, custom-built props, ensuring that every corner of the house was brimming with character and charm. Interestingly, the design of Mickey’s House was inspired by a real home in Wichita Falls, making it a unique blend of real-world inspiration and Disney magic.

Mickey’s House also showcased Disney’s commitment to creating interactive and engaging experiences. Guests could make themselves at home, sitting in Mickey’s chair, listening to the radio, and exploring the many mementos and references to Mickey’s animated adventures throughout the years. This approach to attraction design – where storytelling and interactivity merged seamlessly – was a defining characteristic of ToonTown’s success.

Executive Decisions: Shaping ToonTown’s Unique Attractions

The development of Mickey’s Toontown wasn’t just about creative imagination; it was significantly influenced by strategic decisions from Disney executives. One notable input came from Jeffrey Katzenberg, who suggested incorporating a Rescue Rangers-themed ride. This idea was a reflection of the broader Disney strategy to integrate popular contemporary characters and themes into the park, ensuring that the attractions remained relevant and engaging for visitors.

In addition to Katzenberg’s influence, Frank Wells, the then-President of The Walt Disney Company, played a key role in the strategic launch of Toontown’s attractions. His decision to delay the opening of “Roger Rabbit’s Car Toon Spin” until a year after Toontown’s debut was a calculated move. It was designed to maintain public interest in the park by offering new experiences over time, thereby giving guests more reasons to return to Disneyland.

These executive decisions highlight the careful planning and foresight that went into making Toontown a dynamic and continuously appealing part of Disneyland. By integrating current trends and strategically planning the rollout of attractions, Disney executives ensured that Toontown would not only capture the hearts of visitors upon its opening but would continue to draw them back for new experiences in the years to follow.

Global Influence: Toontown’s Worldwide Appeal

The concept of Mickey’s Toontown resonated so strongly that it was replicated at Tokyo Disneyland and influenced elements in Disneyland Paris and Hong Kong Disneyland. Each park’s version of Toontown maintained the core essence of the original while adapting to its cultural and logistical environment.

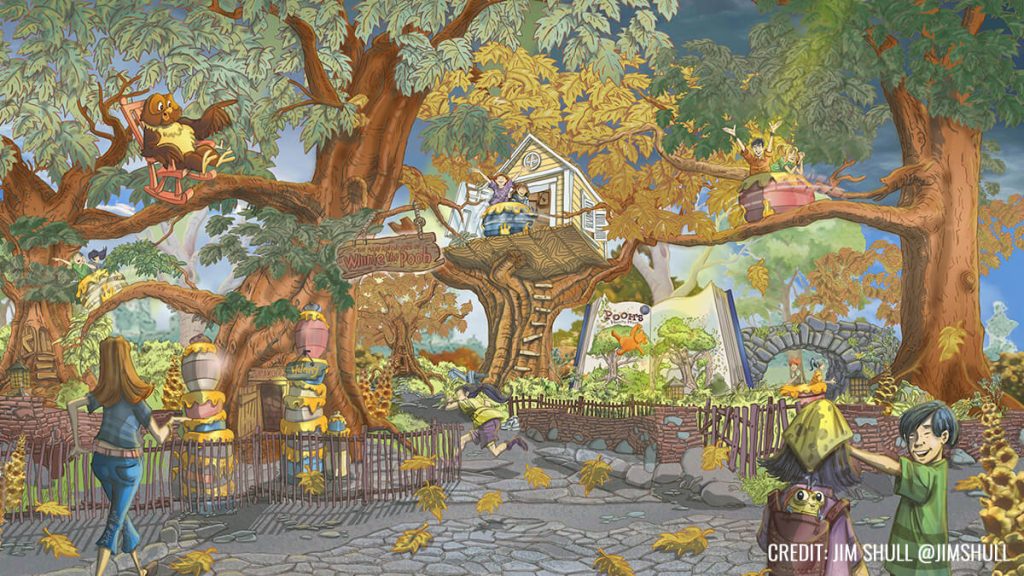

Evolution and Reimagining: Toontown Today

As we approach the present day, Mickey’s Toontown has recently undergone a significant reimagining to welcome “Mickey & Minnie’s Runaway Railway” in 2023. This refurbishment aimed to enhance the land’s interactivity and appeal to a new generation of Disney fans, all while retaining the charm that has made ToonTown a beloved destination for nearly three decades.

Dive Deeper into ToonTown’s Story

Want to know more about Mickey’s Toontown and hear some fascinating behind-the-scenes stories, then check out the latest episode of Disney Unpacked on Patreon @JimHillMedia. In this episode, the main Imagineer who worked on the Toontown project shares lots of interesting stories and details that you can’t find anywhere else. It’s full of great information and fun facts, so be sure to give it a listen!

History

Unpacking the History of the Pixar Place Hotel

Pixar Place Hotel, the newly unveiled 15-story tower at the Disneyland Resort, has been making waves in the Disney community. With its unique Pixar-themed design, it promises to be a favorite among visitors.

However, before we delve into this exciting addition to the Disneyland Resort, let’s take a look at the fascinating history of this remarkable hotel.

The Emergence of the Disneyland Hotel

To truly appreciate the story of the Pixar Place Hotel, we must turn back the clock to the early days of Disneyland. While Walt Disney had the visionary ideas and funding to create the iconic theme park, he faced a challenge when it came to providing accommodations for the park’s visitors. This is where his friend Jack Wrather enters the picture.

Jack Wrather, a fellow pioneer in the television industry, stepped in to assist Walt Disney in realizing his dream. Thanks to the success of the “Lassie” TV show produced by Wrather’s company, he had the financial means to build a hotel right across from Disneyland.

The result was the Disneyland Hotel, which opened its doors in October 1955. Interestingly, the early incarnation of this hotel had more of a motel feel than a hotel, with two-story buildings reminiscent of the roadside motels popular during the 1950s. The initial Disneyland Hotel consisted of modest structures that catered to visitors looking for affordable lodging close to the park. While the rooms were basic, it marked the beginning of something extraordinary.

The Evolution: From Emerald of Anaheim to Paradise Pier

As Disneyland’s popularity continued to soar, so did the demand for expansion and improved accommodations. In 1962, the addition of an 11-story tower transformed the Disneyland Hotel, marking a significant transition from a motel to a full-fledged hotel.

The addition of the 11-story tower elevated the Disneyland Hotel into a more prominent presence on the Anaheim skyline. At the time, it was the tallest structure in all of Orange County. The hotel’s prime location across from Disneyland made it an ideal choice for visitors. With the introduction of the monorail linking the park and the hotel, accessibility became even more convenient. Unique features like the Japanese-themed reflecting pools added to the hotel’s charm, reflecting a cultural influence that extended beyond Disney’s borders.

Japanese Tourism and Its Impact

During the 1960s and 1970s, Disneyland was attracting visitors from all corners of the world, including Japan. A significant number of Japanese tourists flocked to Anaheim to experience Walt Disney’s creation. To cater to this growing market, it wasn’t just the Disneyland Hotel that aimed to capture the attention of Japanese tourists. The Japanese Village in Buena Park, inspired by a similar attraction in Nara, Japan, was another significant spot.

These attractions sought to provide a taste of Japanese culture and hospitality, showcasing elements like tea ceremonies and beautiful ponds with rare carp and black swans. However, the Japanese Village closed its doors in 1975, likely due to the highly competitive nature of the Southern California tourist market.

The Emergence of the Emerald of Anaheim

With the surge in Japanese tourism, an opportunity arose—the construction of the Emerald of Anaheim, later known as the Disneyland Pacific Hotel. In May 1984, this 15-story hotel opened its doors.

What made the Emerald unique was its ownership. It was built not by The Walt Disney Company or the Oriental Land Company (which operated Tokyo Disneyland) but by the Tokyu Group. This group of Japanese businessmen already had a pair of hotels in Hawaii and saw potential in Anaheim’s proximity to Disneyland. Thus, they decided to embark on this new venture, specifically designed to cater to Japanese tourists looking to experience Southern California.

Financial Challenges and a Changing Landscape

The late 1980s brought about two significant financial crises in Japan—the crash of the NIKKEI stock market and the collapse of the Japanese real estate market. These crises had far-reaching effects, causing Japanese tourists to postpone or cancel their trips to the United States. As a result, reservations at the Emerald of Anaheim dwindled.

To adapt to these challenging times, the Tokyu Group merged the Emerald brand with its Pacific hotel chain, attempting to weather the storm. However, the financial turmoil took its toll on the Emerald, and changes were imminent.

The Transition to the Disneyland Pacific Hotel

In 1995, The Walt Disney Company took a significant step by purchasing the hotel formerly known as the Emerald of Anaheim for $35 million. This acquisition marked a change in the hotel’s fortunes. With Disney now in control, the hotel underwent a name change, becoming the Disneyland Pacific Hotel.

Transformation to Paradise Pier

The next phase of transformation occurred when Disney decided to rebrand the hotel as Paradise Pier Hotel. This decision aligned with Disney’s broader vision for the Disneyland Resort.

While the structural changes were limited, the hotel underwent a significant cosmetic makeover. Its exterior was painted to complement the color scheme of Paradise Pier, and wave-shaped crenellations adorned the rooftop, creating an illusion of seaside charm. This transformation was Disney’s attempt to seamlessly integrate the hotel into the Paradise Pier theme of Disney’s California Adventure Park.

Looking Beyond Paradise Pier: The Shift to Pixar Place

In 2018, Disneyland Resort rebranded Paradise Pier as Pixar Pier, a thematic area dedicated to celebrating the beloved characters and stories from Pixar Animation Studios. As a part of this transition, it became evident that the hotel formally known as the Disneyland Pacific Hotel could no longer maintain its Paradise Pier theme.

With Pixar Pier in full swing and two successful Pixar-themed hotels (Toy Story Hotels in Shanghai Disneyland and Tokyo Disneyland), Disney decided to embark on a new venture—a hotel that would celebrate the vast world of Pixar. The result is Pixar Place Hotel, a 15-story tower that embraces the characters and stories from multiple Pixar movies and shorts. This fully Pixar-themed hotel is a first of its kind in the United States.

The Future of Pixar Place and Disneyland Resort

As we look ahead to the future, the Disneyland Resort continues to evolve. The recent news of a proposed $1.9 billion expansion as part of the Disneyland Forward project indicates that the area surrounding Pixar Place is expected to see further changes. Disneyland’s rich history and innovative spirit continue to shape its destiny.

In conclusion, the history of the Pixar Place Hotel is a testament to the ever-changing landscape of Disneyland Resort. From its humble beginnings as the Disneyland Hotel to its transformation into the fully Pixar-themed Pixar Place Hotel, this establishment has undergone several iterations. As Disneyland Resort continues to grow and adapt, we can only imagine what exciting developments lie ahead for this iconic destination.

If you want to hear more stories about the History of the Pixar Place hotel, check our special edition of Disney Unpacked over on YouTube.

Stay tuned for more updates and developments as we continue to explore the fascinating world of Disney, one story at a time.

History

From Birthday Wishes to Toontown Dreams: How Toontown Came to Be

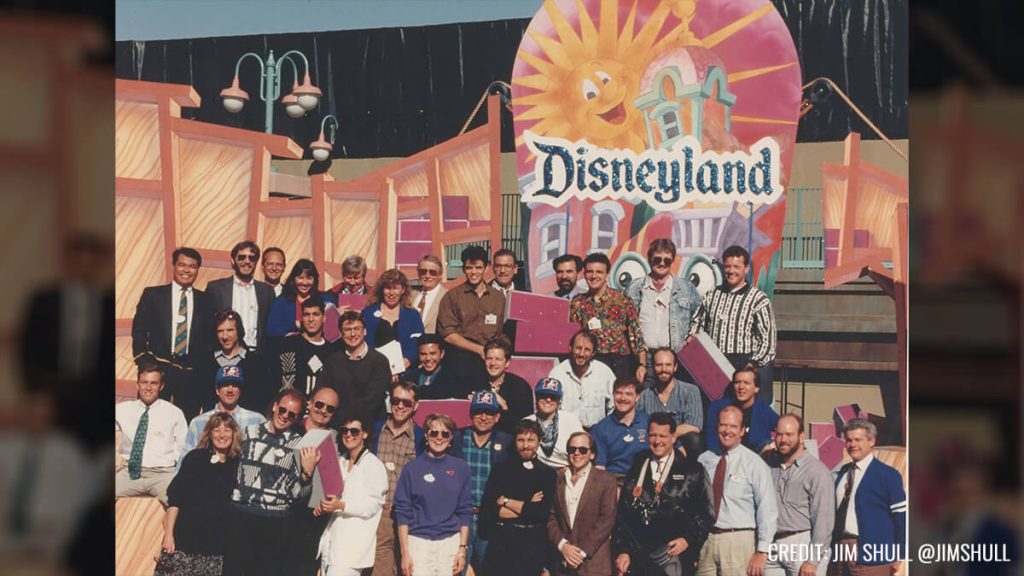

In the latest release of Episode 4 of Disney Unpacked, Len and I return, joined as always by Disney Imagineering legend, Jim Shull . This two-part episode covers all things Mickey’s Birthday Land and how it ultimately led to the inspiration behind Disneyland’s fan-favorite land, “Toontown”. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. It all starts in the early days at Disneyland.

Early Challenges in Meeting Mickey

Picture this: it’s the late 1970s and early 1980s, and you’re at Disneyland. You want to meet the one and only Mickey Mouse, but there’s no clear way to make it happen. You rely on Character Guides, those daily printed sheets that point you in Mickey’s general direction. But let’s be honest, it was like finding a needle in a haystack. Sometimes, you got lucky; other times, not so much.

Mickey’s Birthdayland: A Birthday Wish that Came True

Fast forward to the late 1980s. Disney World faced a big challenge. The Disney-MGM Studios Theme Park was under construction, with the company’s marketing machine in full swing, hyping up the opening of Walt Disney World’s third theme park, MGM Studios, in the Spring of 1989. This extensive marketing meant that many people were opting to postpone their family’s next trip to Walt Disney World until the following year. Walt Disney World needed something compelling to motivate guests to visit Florida in 1988, the year before Disney MGM Studios opened.

Enter stage left, Mickey’s Birthdayland. For the first time ever, an entire land was dedicated to a single character – and not just any character, but the mouse who started it all. Meeting Mickey was no longer a game of chance; it was practically guaranteed.

The Birth of Birthdayland: Creative Brilliance Meets Practicality

In this episode, we dissect the birth of Mickey’s Birthdayland, an initiative that went beyond celebrating a birthday. It was a calculated move, driven by guest feedback and a need to address issues dating back to 1971. Imagineers faced the monumental task of designing an experience that honored Mickey while efficiently managing the crowds. This required the perfect blend of creative flair and logistical prowess – a hallmark of Disney’s approach to theme park design.

Evolution: From Birthdayland to Toontown

The success of Mickey’s Birthdayland was a real game-changer, setting the stage for the birth of Toontown – an entire land that elevated character-centric areas to monumental new heights. Toontown wasn’t merely a spot to meet characters; it was an immersive experience that brought Disney animation to life. In the episode, we explore its innovative designs, playful architecture, and how every nook and cranny tells a story.

Impact on Disney Parks and Guests

Mickey’s Birthdayland and Toontown didn’t just reshape the physical landscape of Disney parks; they transformed the very essence of the guest experience. These lands introduced groundbreaking ways for visitors to connect with their beloved characters, making their Disney vacations even more unforgettable.

Beyond Attractions: A Cultural Influence

But the influence of these lands goes beyond mere attractions. Our episode delves into how Mickey’s Birthdayland and Toontown left an indelible mark on Disney’s culture, reflecting the company’s relentless dedication to innovation and guest satisfaction. It’s a journey into how a single idea can grow into a cherished cornerstone of the Disney Park experience.

Unwrapping the Full Story of Mickey’s Birthdayland

Our two-part episode of Disney Unpacked is available for your viewing pleasure on our Patreon page. And for those seeking a quicker Disney fix, we’ve got a condensed version waiting for you on our YouTube channel . Thank you for being a part of our Disney Unpacked community. Stay tuned for more episodes as we continue to “Unpack” the fascinating world of Disney, one story at a time.