Health Care

Recommended Practices in Caring for Alpacas:

(Sources: Camelid Community Standards of Care Working Group*, the Merck Vet Manual, and general farm experience. PLEASE NOTE: In all cases, please consult with your local vetrinarian to determine the best care for your alpaca.)

Click on the subject or scroll down to learn more!

- BIRTHING: Dystocia, IgG

- BR E ED ING

- FI BER/SHEARING

- G ELDING

- IN JURY/SAFE KEEPING: Hyperthermia - Hypothermia

- AN ESTHESIA

- COMMON INTERNAL PARASITES: Whip Worm - Tape Worm - Stomach Worm - Nematodes - Coccidia - Menengeal Worm

Introduction:

Alpacas are domesticated South American members of the camelid family. These animals differ significantly from other species. Beyond the minimums required to sustain any life, the specifications for their care are unique. Alpacas can thrive in a wide range of environments, from ranches with vast open ranges to small suburban properties, and in almost every type of climate and geography. Some live in dry lot conditions and exist entirely on nutrition provided by their owners, while others live on properties with abundant pasture. These animals thrive in an environment where the relationship with humans and other animals is peaceful, basic security is provided, and life activities that fit their nature are included. With proper care from responsible stewards, alpacas and llamas typically enjoy good health, with an average lifespan of 15 to 20+ years.

This information was gathered prepared with addition and assistance of a number of experienced llama and alpaca owners, including practices from our own farm, most of which has been reviewed by veterinarians and representatives of various recognized llama and alpaca organizations. It contains recommended practices based on up-to-date scientific knowledge and community-wide husbandry expertise. It is intended as an educational foundation for recommended camelid care and, as such, to provide the basis for continuity and consistency in that care. In all cases, please consult with your local veterinarian for your specific need.

In addition to the general practice recommendations, region-specific conditions may exist, necessitating additional or differing measures in those locales to insure the health and well-being of the animals. Where available, a camelid-experienced veterinarian should be consulted for local or regional needs. Additionally, consider joining one or more llama and/or alpaca organizations for continuing education, networking and local owner support. The references provided at the end of this document give more detailed and extensive coverage for various aspects of camelid care.

All animals deserve the best possible environment in which to thrive. There are many ways to assure this. The purpose of "Recommended Practices" is to provide basic and important information on providing that environment for llamas and alpacas, beyond minimum requirements. Each camelid caregiver will have his or her practices to assure animal well-being, based on knowledge of the herd individuals, as well as sound husbandry.

Getting Started: The Basics

* A commitment to care for animals 365 days a year in good weather and bad (unless you plan to board them with another breeder). A budget for expenses of management (and marketing if applicable)

* A rudimentary business plan outlining your objectives for conducting and growing your business (unless you just want alpacas as pets)

* A fenced pasture area for your alpacas, adequate to keep out most predators. A smaller enclosure for catching/ feeding/ handling alpacas and/or Some type of shelter a ppropriate for your weather (barn, loafing shed, large sturdy tent, etc.)

ppropriate for your weather (barn, loafing shed, large sturdy tent, etc.)

* Forage and/or good grass hay (we suggest a mix that has orchard grass as the base)

* Shredded Beet (* with or without molasses ) for extra nutrition - we used daily to supplement our additives

* Whole Flax seed ( and grinder-- ground just seconds before breakfast)

* Garlic Powder (pre-mixed in shredded beet for natural fly prevention and promotes friendly bacteria aiding digestion.)

* Rake, shovel and wheel-barrow/cart for cleaning up poop.

* A mineral/salt, we use Stillwater Minerals

free choice.* Feed supplement suitable for your type of pasture/hay and area soil - Some that we use are: Healthy Coat Fiber Supplement, and Iron Power - Iron/B Complex Supplement.

* Fresh water supply

* Well-fitted halters and leads for each alpaca

* Toenail clippers for alpacas/llamas

* Wormers such as Panacur or Safeguard 10% Suspension paste/liquid drench (We use the liquid), Ivermectin (injectable) Quest Paste, and Corid for treatment of coccidiosis (consult a local vet to determine the requirements for your region)

liquid), Ivermectin (injectable) Quest Paste, and Corid for treatment of coccidiosis (consult a local vet to determine the requirements for your region)

* A First-Aid kit containing vet wrap, antiseptic for cleaning wounds, animal thermometer, antibiotic cream (non-steroid), eye ointment.

* Vet who knows something about camelids or is willing to learn

* A mentor, hopefully the breeder from whom you are buying your alpacas

* A book about basic care, such as Caring for Llamas and Alpacas, by Claire Hoffman; (about $24) and as much information as you can gather from the Internet, libraries, etc. If you have joined AOA (Alpaca Owners Assoc.), they also have an excellent library.

* A list of phone numbers for suppliers, including a professional shearer in your area

* If you know how to give injections or are willing to learn, your vet can give you a list of supplies needed: syringes, needles, injectable wormer, vaccines, epinephrine, dyprone for dire emergencies, etc. (see also, list below)

First Aid Basics:

* Vet wrap

* Ace bandage

* Thermometer

* Lubricant

* Gauze rolls and pads

* Bandaging tape

* Various size syringes, generally 3 cc to 20 cc

* Needles of varying sizes, generally 18 to 22 gauge

* Charcoal (or other poisoning mediator such as Toxiban Suspension)

* Mineral Oil

* Pepto Bismal / Carafate / Immodium D

* Alcohol

* Antibiotics (such as LA 200, Penicillin G, Naxel, Agrimycin)

* Hydrogen Peroxide

* Betadine Solution and/or disposable Sponges

* Anti-bacterial Spray such as Well-Horse

* Antibiotic Ointment and Skin Ointments (such as bag balm, zinc oxide)

* Saline Eyewash Solution and cleanser

* Nitrofurazone Ointment

* Blood-stop powder, keep handy when trimming toenails

* Epinephrine

* Dyprone

* Penicillin

* Thiamine

* Banamine

* Tweezers

* Scissors

* Disposable Gloves

* Disposable Razors

* Heat Pad

* Emergency phone numbers

General Supplies:

General Supplies:

* Clean Stainless Steel Bucket(s)

* Feeders (for grain/mineral salts)

* Scoops / measuring cups for grain

* Heat Pad for Animals

* Worming Medicines (see above)

* Vitamins (such as B Complex, A&D, Vita-charge paste)

* Oxytocin

* Fly Repellent

* Electrolyte Replacement (We use Apple-Dex)

* Shears

* Nail Trimmers

* Halters

* Leads

* Scale

* Flashlight and Batteries

* Basic Care Books

* Woodchips (for absorption in barn)

* Rubber Mats (for barn flooring)

* Micro Chips (we use the bio-therm)

Addional items for Breeders and Cria Care:

* Note pad for health care records

* Blanket/pad for ground to keep cria clean

* Charged iPhone/Camera!

* Blood Sample vials and cards (as needed for progesterone or DNA testing)

* Surgical Scrub Such as Betadine or Disposable Betadine Surgical Scrub Pads

* Ziploc Baggies

* Enema bottle

* Nolvasan or other naval dip solution

* Film or pill canister (to hold dipping solution)

* Feeding tube

* Feeding bottle

* Pritchard nipple or other

* Long Disposable Gloves & Latex Gloves

* Digital 10-Second thermometer

* Lubricant (OB Lube)

* Bulb Syringe

* Dental Floss (for tying off umbilical if necessary)

* Stethoscope

* Weight Scale

* Milk Replacement Formula (Sav-A-Lamb) is what we use.

* Cloth Towels

* Hair Blower/dryer

* Cria coats

* Emergency Phone Numbers

*

IGg Test Kit

* Bo-Se Injectable

* Jump-Start Gel (Microbial Gel)

* Light Kayro Corn Syrup

* Pro-biotic Plus

* Frozen colostrum

* Frozen plasma

*Colostrum and Plasma must remain frozen and does have a shelf life -- typically one year. It's expensive to have shipped over night, but I strongly recommend having on hand if needed. If you have other farms close to you, you can pool resources and have one farm store these and split the costs. You will know within a few hours of birth if you need to have the colostrum, so make sure if someone else is storing this, then make sure you can get to it within a few hours.

Plasma you won't know if you need it until the following day. I recommend running an IgG 24 hours after the cria starts to nurse to test cria if it is a poor doer. When you get those results, you'll know if you need a plasma transfer. So, you'll need to have a plan for these BEFORE cria birth.

NOTE: Powdered colostrum does not contain antibodies needed for the new cria. It's a source of nutrition and calories, but it is best for the cria to have actual mom's colostrum or frozen colostrum with antibodies within 12 hours of birth.

A few valuable resource for medical supplies and equipment:

Light Livestock Equipment

Valley Vet

PBS Animal Health

Useful Llama Items

Stillwater Minerals

Kent Labs Triple J Farms (for plasma)

These lists are a general list of items and is not intended to be all-inclusive. Store all items appropriately and be mindful of expiration dates. For a list of items most appropriate for your area, consult your veterinarian.

Jump to top of page

Nutrition:

Questions we need to ask ourselves:

1. What do they need?Simply to survive, not very much. On the Altiplano, of Chile, Peru, and Bolivia they subsist on anything from lush grass during the rainy season to very little ground coverage for a good portion of the year. They have to breed for cria births during the rainy season so that the females will have enough milk to keep the cria alive.

Because of the value of these animals in North America, we are not content to have the mortality rates of South America, I learned while visiting Peru with Dr. Purdy, and Dr. Dewitt, that 30% of the cria do not live beyond one month of age. The fertility rates, are also quite high, reportedly anywhere from 30% to 50%. There are those who believe that, when it comes to alpacas, because they are hardy animals, that less is better. A well known Veterinarian from Kentucky, completed a study of 22,000 Llamas and 3,000 Alpacas across 27 states. He concluded that 80% of Lama medical problems are nutrition related. He noted, that breeders with 10 to 15 years experience were losing animals due to malnutrition.

We must however not get carried away with the thought of feeding our animals well, to the point of overfeeding. Some alpacas will over eat and become fat if given the opportunity, Overfed alpaca can also reduce greatly the quality of their fiber.

The best information we have to date, has been published by Dr. LaRue Johnson DVM. of Veterinary Clinics of North America. Added to this information are levels published by Dr. Murray Fowler and Dr. Brian Evans. The levels of key elements in total diet are:

| Recommended: | Sample Results | |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | 10% - 16%

|

10%

|

| Calcium | .6% - .75%

|

.46%

|

| Phosphorus | .3% - .5%

|

.35%

|

| Potassium | 1% - 1.5% (Evans)

|

2%

|

| Magnesium | .34% - .4% (Evans)

|

.13%

|

| Fibre | 25% +

|

%

|

| TDN | 55% - 65%

|

57%

|

| Vitamin E | up to 400 iu/day

|

/day

|

| Selenium | up to 2mg/day

|

mg/day

|

| Zinc | 60 - 70 ppm

|

ppm

|

| Copper | 5 - 10 ppm (Fowler)

|

ppm

|

| Vitamin A | 15000 iu/day (Fowler)

|

iu/day

|

| Vitamin D | 1500 to 3000 iu/day (Fowler)

|

iu/day

|

Fat Soluble Vitamins

Vitamin Adeficiency may result in reduced resistance to infection, impaired growth and improper tooth and bone formation. Zinc is necessary for the mobilization of Vitamin A.

Vitamin Dplays a dual role as both a vitamin and a hormone. It functions to increase absorption of calcium and phosphorus. Vitamin D conversion in the skin is restricted by lack of sunlight due to our North American northern latitudes as compared to the camelids native to South America. The fiber of both llamas and alpacas decreases the amount of sunlight reaching the skin. In addition, in the warmer parts of the United Stated States, llamas and alpacas are encouraged to spend the daylight hours in the shade. A deficiency of Vitamin D is responsible for rickets. In its milder form it may be blamed on poor conformation in the show ring.

Vitamin Eis an antioxidant and is enhanced by other antioxidants, such as selenium. Its function is to stabilize membranes and protect them against free radical damage and to protect tissues of the skin, eye, and liver. In addition, Vitamin E protects and vitalizes the testicles for improved virility.

The Vitamin B Story:

Everyone knows B-Vitamins are essential for good health. In fact, they're a critical component in the metabolism of all species of animals and plants. They're also a well-recognized requirement for normal growth and other physiological functions. But, in healthy adult llamas or alpacas, sufficient levels of B-Vitamins are already produced by microorganisms within the rumen. And, with the exception of young or stressed animals, "B" supplements may not be needed at all.

Previously known as a single vitamin, "B" actually consists of several distinct water-soluble vitamins with different functions. That's why they're typically referred to as B-complex Vitamins. And while only very small amounts of B-Vitamins are needed, they're vital to the health and vigor of your alpacas. B12, for example, contributes to growth and normal appetite. Niacin is needed for hair and skin health. Riboflavin is critical for a variety of growth and reproductive functions. Thiamine aids in growth, heart function and temperature regulation. Pantothenic acid promotes proper muscle and nerve function. And pyridoxine is necessary for normal growth and development.

The following list includes the major water-soluble B-Vitamins.

B-Complex Vitamins:

THIAMIN - B1

RIBOFLAVIN - B2

NIACIN - B3

PANTOTHENIC ACID - B5

PYRIDOXINE - B6

COBALAMIN – B12

Why The Rumen Is The Best Source Of "B": The fact is, B-Vitamins are generally not needed by ruminants like llamas and alpacas. Even when there's a lack of "B" in the feed itself, the rumen synthesizes and produces an ample supply of various B-Vitamins needed by the animal. This is why deficiencies are relatively uncommon in most alpacas-especially once they've matured and the rumen is well-developed.

However, deficiencies can occur as a result of poor health or improperly balanced rations (low-protein levels or mineral deficiencies). These factors can lower the number of microorganisms in the rumen, or drastically alter its synthesis process. If normal bacterial action doesn't take place in the rumen, B-Vitamin production may be too low for the animal's healthy growth and development.

Until the age of 6 weeks to 3 months, crias don't yet have a fully functioning rumen. Therefore, to ensure effective rumen function for adult llamas and sufficient levels of "B" for crias, it's essential to provide both with a properly balanced diet.

Water Soluble Vitamins

Vitamin B1deficiency may result in gastrointestinal disturbances, constipation and intestinal inflammation. 90-96% of B1 is produced in the rumen by microbial action, it is questionable as to whether this synthesis is adequate for an animal's needs, particularly when hay is fed.

Vitamin B2functions with coenzymes and is important in energy production and essential for normal fatty acid and amino acid synthesis. Deficiency may result in dermatitis, dryness of skin and fiber and also, malformations and retarded growth in young llamas and alpacas.

Vitamin B3deficiencies affect every cell, but most critically the tissues with rapid cell turnover, such as the skin. Classic symptoms are dermatitis and diarrhea.

Vitamin B12plays a role in the activation of amino acids during protein formation. Proper DNA replication is dependent on the function of coenzymes and Vitamin B12 as a methyl group carrier. The need for Vitamin B12 is increased by pregnancy. "Ill Thrift" may in part be a result of cobalt or vitamin B12 deficiency, possibly coupled with a toxic plant.

Biotinfunctions to aid the incorporation of amino acids into protein and reducing the symptoms of zinc deficiency. Biotin play a major role in the production of fiber.

Jump to top of page

Minerals are components of body tissues and fluids that work in combination with enzymes, hormones and Vitamins. They work either in combination with each other or compete with each other for absorption. Some minerals actually enhance the absorption of other minerals. That is why it is important to balance the minerals specifically for llamas and alpacas.

Calciumis the most abundant mineral. 98% of the calcium in the llama or alpaca is in bone tissue and is therefore critical to structure and strength. Calcium absorption is Vitamin D dependent and a lack of either one will result in retarded bone growth. The ratio of Calcium to Phosphorus in the overall diet is critical. Diets high in phosphorus and low in calcium have been linked to soft tissue calcification and bone loss.

Phosphorusis the second most abundant mineral in the llama and alpaca. Many enzymes and the B Vitamins are activated only in the presence of Phosphorus. Calcium and Phosphorus are closely related. Fluctuations in one mineral will be reflected by subsequent fluctuations in the other. The natural ratio of Calcium to Phosphorus in bones and teeth is 2:1, this is an ideal ratio in the overall diet. Alfalfa and grains are higher in Calcium than the ideal 2:1 ratio; therefore, the supplementation of higher levels of Phosphorus are necessary.

Potassiumis used in intracellular fluid transmission. Potassium functions to maintain cellular integrity and water balance and is involved in muscle contraction and protein metabolism. Hot weather or stress may deplete potassium.

Irondeficiency may be evident in a low red blood cell count. The condition of anemia will be aggravated by parasites.

Magnesiumis associated with tissue breakdown and cell destruction. Also helps in the formation of urea and as such is important in removing excess ammonia for the body. This helps the llama or alpaca to deal with hot weather and stress.

Manganesedeficiency may be caused by large amounts of calcium and phosphorus in the intestine. Signs of a deficiency are sterility and testicular degeneration, weak offspring and poor survival rates.

Cobaltcan replace zinc in some enzymes and participates in the biotin dependent oxalaxetate. Deficiency shows up as emaciated and anemic animals.

Iodinedeficiencies may include impaired physical development of the fetus, a lower basal metabolic rate and poorly formed bones.

Coppercompetes with zinc for entry from the intestines and an increase in zinc might precipitate a copper deficiency. During growth, the largest concentrations of copper occur in developing tissues. Deficiency may result in a low white blood cell count, kinky or poor quality fiber and impaired growth. Impaired immunity and increased risk of prolonged duration of infections are all indications of a copper deficiency. *CAUTION: Copper should not exceed 60 mg. per head per day, or 20 ppm in the total feeding program. Levels of Copper considered normal for other species may be toxic to lamas. Research has indicated that alpacas and llamas should have 10 to 20 ppm in the total feeding program and may become toxic in the 60 ppm range over time. If you are in doubt, please contact your Veterinarian.

Seleniumis a trace mineral that functions either alone or as a part of enzyme systems. Selenium parallels the antioxidant and free radical scavenging action of Vitamin E. In general Vitamin E and selenium do not replace each other but are involved in overlapping systems. In llamas and alpacas selenium plays a major role in the normal development of the fetus during pregnancy and vitality of newborn. Llamas and alpacas require higher levels of selenium than most other species.

Zincfunctions indirectly as an antioxidant and is used in bone metabolism and plays a major role in necessary skin oil gland function. Zinc also functions in DNA synthesis, wound healing, the immune system, and reducing infant morbidity. Chelated form of zinc is preferred and is less effected by competitions for absorption from other minerals.

A mineral panel includes:

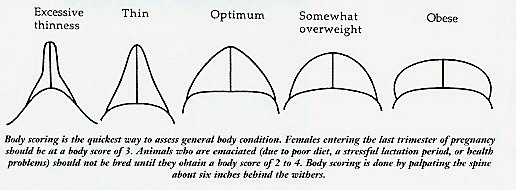

Under basal conditions, an alpaca will eat 1.5% to 2% of their body weight per day. At 2% a 150 lb. alpaca will eat about 1.4 kg or 3 pounds of food per day on a dry-matter basis. Legumes are usually not needed and may result in obesity. Body condition can best be assessed by palpating the amount of tissue over the lumbar vertebrae , typically referred to as body scoring. See 3) Physical Assessment below for further details.

Most mature males, and females during mid-gestation, will maintain appropriate body condition on 10-14/16% crude protein grass hay with total digestible nutrients (TDN) of 50-60%. Late gestation and heavily lactating females require a slightly higher percentage of crude protein and TDN of 65-70%.

Jump to top of page

2. What are they getting from pastures and hay?We need to analyze the grass/pasture and hay to determine the need for and types of supplements that are required for our alpacas. With this information and the above information we can do the calculations necessary. Results from a sample forage analysis coming soon.

3. Supplementation:If you ask people if they feed their alpacas a supplement about 95% will say "yes", and of those about 60% will say "in the winter". If you ask what they supplement you will hear all kinds of answers, but mostly you will hear grain, Alpaca/Llama Pellets, our own grain mixture, Free choice minerals, mineral blocks.

If you want to feed grain, first of all make sure that it is cracked or preferably rolled, Alpacas don't digest whole grain very well, and secondly know why you are feeding it. When feeding grain, you are adding a carbohydrate for extra energy or heat (in winter) and with some grains a small amount of protein. Grains are deficient in Calcium, Phosphorus and trace minerals.

If you wish to use free choice minerals you must understand that you are going to get a very wide range of results in your animals. There are some alpacas that will eat up to 50 grams of a mineral powder or more, per day, and many will eat none at all. If the aim is to supplement say 2 mg of selenium/alpaca/day and your free choice mineral supplement has 125mg/kg you better hope the largest consumer of that product does not eat more than 15 to 20 grams a day, and if the product has a low of 30 mg/kg you have to hope that the one that consumes the least amount of the product eats at least 60 grams/day. In reality it is hard to determine exactly what your animals are getting on an individual basis.

The trick to uniform supplementation is to provide the required elements, in the right concentrations, in a prepared feed, such as pellets, that the alpacas want to eat so that they will get their share.

4. To determine if the supplementation is effective, you may do periodic blood sampling.Routinely sample alpacas that are either on the low or high end of the scale, for any particular elements, compared to other alpacas, along with random samples from other alpacas. We do a mineral panel of seven elements, with occasional add ons such as zinc. When making a change to the diet with specific results in mind, allow about 2 or 3 months before doing the next set of blood samples to see if the change has given us the desired result. Clinical Pathology:Hematology and clinical chemistries are similar to those in other species with a few significant differences. Camelid RBC are relatively small and may produce anomalous results when evaluated using an automated cell counter. Therefore, instrument adjustment or manual determination is needed for accurate estimations of RBC numbers and the RBC indices.

Normal PCV is 27-45%, and normal RBC numbers are 10.1-17.3 × 106/µL. Normal WBC counts are 8,000-21,400/µL.

Reasons that nutrition is so important:

Viable birth weights - Proper growth rates - Proper development of all body parts, eg. Straight legs etc. - Disease resistance - May eliminate the need for injections re: selenium, vitamins E, A,& D - Healthy skin, thus proper follicle and fibre alignment. Gives the animals genes the ability to live up to their full potential. Geneticists tell us that genes are responsible for about 60% of the animals makeup, the remainder is environmental.

Seasonal Hypovitaminosis D:

Characterized by diminished growth, angular limb deformities, kyphosis, and a reluctance to move, can be a problem in heavily fibered animals raised in regions with poor sun exposure during winter months. The problem is most severe in rapidly growing, fall-born crias. Serum phosphorus of <3.0 mg/dL, a calcium:phosphorus ratio of >3:1, and vitamin D concentrations of <15 nmol/L in crias <6 mo old are diagnostic. Normal phosphorus and vitamin D concentrations in this age group are 6.5-9.0 mg/dL and >50 nMol/L, respectively.

Other Practices to follow:

1. Provide continuous access to potable water. The animals should not be required to break through ice or eat snow for their water. In extreme heat, water that is cool to the touch encourages consumption and helps avoid dehydration. In extreme cold, lukewarm water does the same. Consider periodic water quality testing.

2. Provide daily access to quality, mold-free hay and/or nutritious pasture. In general for adult maintenance, total feed should contain 10-12% crude protein, dry matter basis, offered at the rate of 1.5%-3% of body weight. Growing youngsters and late term pregnant or early lactating females may need 12-16% crude protein, dry matter basis. This may be obtained by using forage with higher protein content and/or a high-protein supplement. Because of subtle differences, llamas require the lower levels of protein while alpacas requirements are higher. However, individual animals can require more or less feed. Use Body Condition Scoring (BCS) (see reference below) and consult with a veterinarian or animal nutritionist to determine

individual needs.

3. If not pre-mixed into a supplemental feed being offered, provide free choice access to minerals appropriate for the species and the region. (A loose form is preferred.) Take any known mineral toxicities into consideration (e.g., copper, selenium).

4. To feed a cria that requires human intervention, by utilizing a feeding tube or bottle regimen that minimizes human bonding. Supplemental feeding by humans should be done only when medically necessary and the cria should continue to reside with its mother and/or the herd to ensure appropriate behavioral development. Inappropriate animal-human bonding may result in severe behavior problems.

Jump to top of page

Physical Environment:

1. Provide natural or man-made shelter with sufficient ventilation and space to allow each llama and alpaca to find relief from environmental conditions (e.g., extreme cold, heat, humidity, precipitation, wind chill, waterlogged ground/standing water during periods of wet weather).

2. Provide a heating source or cooling measures when temperatures reach extremes, whether at home or traveling. Heat stress (hyperthermia) and hypothermia are life-threatening conditions. (See "Safe-keeping" section for more information.)

3. In enclosed areas, manure should be routinely disposed of, mud prevented, and any urine build-up treated to prevent parasite problems and disease.

4. Provide fencing of sufficient height and strength to safely contain alpacas in designated areas. Fencing design should prevent animals from becoming entangled. Barbed wire is not recommended.

5. House only the number of animals per enclosure that allows free and independent movement of each animal when not at work with a human, as well as the ability to exercise each day. Physical location and conditions (i.e., terrain, vegetation, availability of pasture, etc.), as well as herd composition (males, weanlings, females, etc.) will dictate the appropriate number of animals that can live within a defined area. As a general rule of thumb, an area of 15 square feet per alpaca would be a minimum.

6. Alpacas are browsing and grazing animals. Where possible, provide them the opportunity to browse and graze daily.

7. In temporary situations such as at shows, or in case of health problems, alpacas may be kept in small spaces for a limited period of time. For longer periods (e.g., animals that are in quarantine), they should be exercised each day.

Jump to top of page

Social Environment:

1. Alpacas need to live in association with other herd animals, preferably at least one other alpaca. Without appropriate companionship, most will fail to thrive. Therefore, it is recommended that alpacas never live alone. An alpaca should not be raised as a single baby away from any other camelids.

2. Alpha or highly territorial males may need to be corralled separately, but should be within sight of other alpacas.

3. Crias should remain with their dams until at least four months of age. (Six months or seventy pounds is recommended to promote normal behavior and to assure good nutrition (allow for maturation of the fore-stomach)). When deprived of this herd environment during their growth and development, they can develop severely abnormal ways of relating

to humans at sexual maturity or earlier.

4. Crias should never be sold as pets to be intentionally bottle-fed. Bottle-feeding should take place in a herd environment and only when medically necessary to ensure the health of the dam and/or the cria.

Jump to top of page

Routine Husbandry:

What is A Parasite?

A parasite is an organism that grows, feeds, and is sheltered on or in another type of organism while contributing nothing to the survival of its host. In this instance, the host is our alpacas although all other livestock become the hosts for parasites too. There are two classifications of parasites that affect our alpacas. The first one is Internal parasites, parasites that live and feed inside the alpacas body. These are most often different varieties of worms that live and multiply in the small intestine or the stomach of the alpaca. The second classification is External parasites, those that live and feed off the outside of the alpacas body. Some examples of external parasites are ticks, flies, mosquitoes, lice, and mites.

Affects of Internal Parasites:

There are many types of internal parasites known that infect alpacas and keeping our alpacas safe from these parasites is a year-round job for the alpaca owner. If parasites are not controlled, the alpaca can become unhealthy and unthrifty. A heavy load of parasites can cause the alpaca to become sickly and lose weight since the worms living in the alpaca steal a lot of the nutrition that is needed by the alpaca. Internal parasites can be a severe problem to alpacas sometimes even causing death.

Preventive Measures:

Herd Management, Pasture Management, Soil Management

Good herd management is the primary prevention of parasite problems. A good nutritional program and awareness of the overall health of your animals is the first basic, but very important, step. Parasites are more likely to seek out and attack weak or failing animals. Good sanitation, pasture rotation, and the weather also play a big part in the control of parasites on your farm. The weather can make a big difference in parasites on your farm. Many think the winter's cold temperatures kill the parasites, but in fact the summer heat is more effective in killing parasites.

The Life Cycle Of Parasites:

Without proper management, the internal parasites become a constant cycle. The worms live inside the alpaca getting nutrition from the alpaca's body. When the worms are adult, they lay eggs. The eggs get passed out of the alpaca in their feces, or manure, and end up in the pasture. Then the eggs either hatch into larva in the manure or on the ground. Rain then washes the manure off of the larva and the larva is left to live on the blades of grass. Then alpaca may swallow the larva while grazing. Once inside the nice environment of a warm alpaca, the eggs and larva will mature into adults in about three weeks. These adults now lay more eggs and the cycle starts all over again. So if the alpaca owner does not practice good de-worming herd management, the animals will eventually have a very heavy load of adult parasites. Carrying a heavy load of internal parasites also means a alpaca is getting only partial value from his food.

What about the alpacas that are wild in the mountains of South America and don't have owners to de-worm them? Why don't they get sickly from parasites? alpacas that are out in the wild travel a large area while grazing and browsing. So, since they are moving from area to area, most of the time they are in new, clean grasses that do not contain eggs and larvae so they are not ingesting eggs. Our alpaca herds here are often in smaller confined areas and if there are too many alpacas for the area (over crowded pastures), then the chance of having parasites is much greater.

Jump to top of page

Common Internal Parasites

A useful reference for Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Parasites in Camelids and Small Ruminants is a link here. (Dr. Stephen R. Purdy, DVM)

The most common signs of internal parasites are generally diarrhea and weight loss. These are some of the most common internal parasites that we encounter here in the Midwest area.

Trichuris

- Commonly known as Whipworms in the Intestine; The eggs of this species may survive for years. This worm lives in the large intestine of the alpaca. The eggs are passed in the feces and the larva develops inside of the eggs. When eaten by the alpaca or the host, the eggs hatch in the small intestine and then migrate into the large intestine and develop into adults. The adults then lay eggs to continue the life cycle.

Moniezia

-

Commonly known as Tapeworm. A long tapeworm passed in a soft stool. The head of a tapeworm. The adult is a long, white, flat worm that is in segments. A small single segment of the tapeworm. This is what you will normally see in the alpaca poop that looks like a grain or rice. The flat tapeworm stretched out. This is not the complete worm as some segments have come off. The adult tapeworm is a white flat worm that is in segments. The tapeworm attaches to the wall of the alpaca's small intestine. Segments, or pieces of the tapeworm, which contain eggs, are passes into the feces and may be seen in the alpaca's manure. They will look like small grains of rice. The eggs are then eaten by the oribatid mite, an intermediate host. This mite lives on the grass or on the feces and contains the tapeworm larvae. Now the mite is eaten by the alpaca while eating pasture grasses. The larvae attach to the alpaca's intestinal wall, mature into adults, and continue the life cycle.

Trichostrongylus

- Commonly known as stomach worm. Strongyle Egg. These eggs develop rapidly, hatching in less than twenty hours in summer temperatures (70 - 80 degrees F.) If the eggs dry out before they hatch they become dormant and can survive for as long as 15 months. It is not often possible to identify strongyle eggs to genus level as the eggs of most strongylid and trichostrongylid species are similar in appearance and overlapping in size. If identification is necessary the fecal sample must be cultured to provide L3 larvae for further examination. These are very small stomach worms that live in the small intestine of the alpaca. The eggs are passed in the feces. They hatch and develop into larvae in the soil and in the feces. The alpaca may then eat these larvae from the soil or from their feed or water. The larvae grow to adulthood in the stomach and small intestine.

Nematodirus

-

(thread-necked strongyle) These eggs hatch very rapidly in wet weather. Cool, wet weather and lush, moist pastures are ideal conditions for eggs to live. The eggs of this parasite are very large and are distinctive under the microscope. They are very sturdy eggs and may even survive the winter in the feces or the soil. The larvae develop inside of the egg and may survive for several months in the soil or in vegetation. The alpaca then eats the larvae on the pasture grasses which then mature into adults in the alpaca's small intestine.

Jump to top of page

Coccidia

- Summary: Eimeria (Coccidia)

- Coccidia are tiny one-celled organisms which multiply in the intestinal tract of many animals. The resulting disease, called coccidiosis, is most common in young animals or animals that are stressed - possibly from moving to a new farm. The disease is more common in the fall and winter months. Coccidia are spread in the feces of an infected animal and most commonly exists when animals are overcrowded into small areas or where unsanitary conditions exist. However an animal must ingest a large number of coccidia organisms in order to get sick. If an animal ingests only a small amount, he probably will not get sick and it will produce immunity to this disease. The main sign of coccidiosis is diarrhea. Depending on the level of infection, the diarrhea may become severe and blood may be present. Then the animal becomes depressed, loses weight, becomes dehydrated, and may become very sick. Death can occur. Corid is the most common treatment for coccidiosis and can be given by mouth or in the drinking water.Coccidia is very species specific. There are four species known to be found in lamas, eimeria alpacae, lamae, macusanienis, and punoensis.

Identification: It is difficult to distinguish between e. alpacae and e. lamae as they only differ in size by ~ 10 microns and both are treated effectively with Corid. E. macusanienis is easily identified by its avocado shape and is quite large and is best treated with Albon. There have not yet been any e. punensis in an alpaca.

Treatment: The recommended dosage for amprolium (the active ingredient in Corid) is 10mg/# of BW for 5 days. The preventative dose is 2.5mg/# for 21 days. The administration directions on the 9.6% solution is for cattle and is calculated assuming that cattle will drink 1 gallon of water per 100#'s of BW. Alpacas will consume ~ .5 to .75 gallons of water per 100#'s of BW. Consumption can vary depending on the ambient conditions and the available forage. It may be wise to estimate the daily water intake slightly and use the rate of .5 gal per 100# BW. The 9.6% (.096) solution means that a liter of the solution will contain 96g of Amprolium and 1ml will contain 96mg. A one gallon container of Corid contains 363.36g of Amprolium (96g x 3.785).

First you should know the total weight of the animals that you are treating. You will also need to know the weight to calculate the estimated water consumption.

Example: Total BW = 2,200#. Treatment dosage 10mg/#, 2,200 x 10mg/# = 22,000mg or 2.2g needed to treat the herd 22,000mg divided by 96mg/ml = 229ml needed to treat the herd or 229ml divided by 30ml/fl oz = 7.6fl oz needed to treat the herd for one day. Make your calculations for every group of animals.

Now you need to get the Amprolium in the alpaca. There have not been many published numbers on the water consumption of alpacas, but consumption can vary depending on the ambient conditions and the available forage. It may be best to under estimate the daily water intake slightly and use the rate of .5 gal per 100# BW. In this example, the herd is estimated to consume 11 gal per day (2,200/100 x .5). The more buckets of water that are offered; the greater the chance that everyone will get the required dosage.

Amprolium is a thiamine analog and competitively inhibits the active transport of thiamine. The coccidia are 50 times as sensitive to this inhibition as is the host.

Should you choose to supplement B vitamins during treatment it is not recommended to give orally as it will offset the the oral coccidial treatment. Many probiotics contain B vitamins.

Dr. Evans recommends 20-25 mg/lb of body weight of Amprolium for the treatment of coccidia. It is most commonly dosed at a rate of 10mg/# which has been the recommended dosage. With 96mg/ml, an alpaca weighing 100#'s would require ~10ml of 9.6% Corid solution for a daily dose (100# x 10mg/# divided by 9.6mg/ml).

Vets have also recommended the 5mg/lb, but may not be afraid to go with 10mg/lb for heavy infestation. Alpacas also don't drink as much water as cattle so treating a herd with treated water could lead to under dosing if all the water is not consumed when given at the cattle rate of 1gal/100lbs. Sample guideline: alpacas drink 1/2 - 3/4 gal/100lbs of BW.

Albon. also used to treat coccidia, is available in a 12.5% solution. Each ml contains 125mg of sulfadimethoxine. I have always used this product at the recommended label dosage of 25mg/# on day 1 and 12.5mg/# for 4 days. An alpaca weighing 75#'s would require 15ml for the first day and half that amount on the next 4 days (75# x 25mg/# divided by 125mg/ml). It has been noted that Albon may be the preffered treatment for cria.

Meningeal Worm in Alpaca: Parelaphostrongylus

Meningeal worm is a parasite that affects alpacas. A parasite whose natural host is the white-tailed deer. This is a natural parasite which lives in, but does not affect, white-tailed deer. Read the questions and answers below to become informed about this parasite.

What is meningeal worm?Meningeal worm is a great concern to alpaca owners in areas, particularly in the North Eastern states, where white-tailed deer have a heavy population. Although we have white-tailed deer in Massachusetts, luckily this doesn't seem to be a very large problem here. There has been no evidence of Meningeal Worm on the island of Martha's Vineyard.

How does my alpaca get m. worm?First, you must reside in an area where white-tailed deer exist. Eggs hatch in a deers lungs. The larvae are coughed up and swallowed by the deer. The larvae are then passed to the feces and excreted onto the ground. The alpaca then may inadvertently ingest the snail when browsing and become infected. The larvae find an intermediate host in snails and slugs. Your alpaca ingests the infected snail or slug. Once the larvae are in the stomach, they penetrate the stomach wall and enter spinal nerves. Then they travel to the spinal cord or brain, migrating into the central nervous system causing neurological abnormalities in the alpaca. The disease cannot be passed without the ingestion of an infected snail or slug.

What are the symptoms of meningeal worm infection?Some of the symptoms seen might be: Staggering, rear leg weakness, lameness, uncoordinated gait, stiffness, paraplegia, paralysis, circling, abnormal head tilt, blindness, gradual weight loss, inability to eat.

Can m. worm kill my alpaca?Yes. Damage to the central nervous system can be severe enough to cause death, if aggressive treatment is not begun immediately.

How is the parasite detected?There is no definitive way to detect it in a live animal. Symptoms and lab values are used to diagnose m. worm.

How is m. worm treated once an alpaca is infected?Usually, some type of dewormer is used to kill the parasite. Steroids and anti-inflammatories are used to prevent inflammation and swelling from damaging the spinal cord. Supportive care is, also, used in the form of physical therapy. Keeping blood flow to muscles by massaging helps keep them healthy and allows the animal to recover better.

Will my alpaca recover completely?Depends on how much damage was done. Once the larvae migrate into the nervous tissue, any damage that occurs is usually irreversible.

Can an infected alpaca pass the meningeal worm to other alpacas?Your alpaca must ingest an infected snail or slug to get m. worm. Alpacas are considered a dead-end host. The larvae in alpacas do not mature and produce eggs that mature into larvae that pass out of the animal. They stay in the central nervous system.

How do I prevent meningeal worm in my alpacas?Prevention is the key. The current practice has been to give a dose of Ivermectin every 30 days to alpacas in areas with white-tailed deer. However, overuse of Ivermectin has resulted in increasing drug resistance among parasites in alpacas. Work with your vet. Your worming program should be tailored to your individual farm and geographic area. You can put up a deer-proof fence with a gravel or paved area along the outside of the fence to attempt to keep snails and slugs out of your pastures. This is expensive. You can use a molluscicide, but it might be poisonous to your alpacas, so be careful. Your vet should have up-to-date information to prevent meningeal worm infections.

Jump to top of page

Controlling The Parasite Problem :

As part of preventive health maintenance for alpacas, owners de-worm them with various medications on a proper deworming schedule. Controlling the number of eggs and infective larva that a alpaca consumes is the starting point of any effective de-worming program. The de-worming schedule is important as well as the type and dosage of medication administered.

We are increasingly diagnosing resistance among intestinal parasites in llamas and alpacas. We recommend doing a follow-up fecal exam 2 weeks after treatment to confirm that the treatment has worked. A fecal egg count reduction test (checking the parasite egg count before and 14 to 21 days after de-worming medication is given) allows evaluation of de-worming efficacy. We expect to see >90 % egg reduction if successful. These tests can be done using the Modified Stoll's Fecal Test. This is the only test available sensitive enough to detect the low egg counts expected after de-worming.

When de-worming, the entire herd could receive the medication - except for those females that are within 30 days of birthing or within 30 days of breeding. (Females in this stage should not receive any medications.) Then after approximately three days the pastures should be cleaned of the manure on the ground to prevent the alpacas from re-infecting themselves with parasite eggs in the pasture. The eggs take 3-4 days to mature so you have that length of time to remove manure from the contaminated pastures. This will greatly decrease the chances of new infections. Or, another good method is pasture rotation: put the animals into a new, clean pasture until the first pasture is cleaned and sun dried.

However de-worming is not the only effective way to help control parasites. Managing your alpaca's environment is one of the best strategies for parasite control. Since the major objective is preventing pastures from being contaminated with worm eggs, manure removal from their barn areas and pastures will greatly help in breaking up the parasite life cycles. When cleaning pastures, although not all the manure may be able to be removed, the manure is getting raked and broken up, so on hot, dry days, the sun dries out the eggs and larvae and they die. Parasitic larva in manure in the sunlight dries out whereas larva in manure in moist, damp, dark areas survive for months. Cool, wet weather and lush, moist pastures are ideal conditions for eggs to live.

Hay racks, feed dishes, water buckets, and automatic waterers should be regularly cleaned to prevent any possibility of parasites living there. alpacas should not be fed on the ground, as this would increase the likelihood of alpacas infecting themselves with parasites that may be living on ground vegetation. To check how effective your parasite management program is you can have your veterinarian check your alpaca’s feces for parasite eggs.

Some infective larva, such as Nematodirus and Trichurs, can even become dormant over the winter and survive temperatures to 20 below zero. Then they can become infective again about one month after pastures begin new growth in April and May. For this reason, only third generation wormers that are larvacidal are recommended for treatment. Examples are Ivermectin, Oxbendazole (Synanthic), and Albendazole (Valbazen). A third generation wormer attacks the eggs, the larva, and the adults. Panacur or Safeguard is only effective for adult worms and does not affect the larva. Ivermectin or Dectomax is mainly effective on Brown Stomach Worms and Meningeal Worm. Both Valbazen and Synanthic address Nematodirus and Trichurs. Strongyles normally will respond to Fenbendalzole (Panacue or Safeguard) or Ivermectin.

General Recommendations:

Every worming program should be tailored specifically to the individual farm: no one policy is going to be appropriate for every situation. These are best worked out in conjunction with your local veterinarian and we would be happy to consult with them should further advice be required. In general though, we need to be concerned about the potential for parasite drug resistance in our animals since indiscriminate use of anthelmintics (these are drugs to treat internal parasites, e.g. Panacur, Safeguard, Ivermectin, etc) can lead to "problem parasites" and we only have a limited number of drugs at our disposal. For this reason, periodic fecal exams and judicious use of anthelmintic drugs is the responsible way to ensure that your farm remains disease-free.

Some farms may only require dosing for gastrointestinal parasites twice a year and others may need to worm every 2 months. The frequency of worming depends a lot on your stocking density and management practices. Also, always dose animals individually based on weights: I strongly encourage you to purchase a set of scales for your farm. Under-dosing is another easy way to induce drug resistant parasites. In 2003, we have seen the emergence of "dual-resistance" herds. These herds have intestinal parasites resistant to BOTH ivermectin AND fenbendazole. This is a very grave concern and we have seen many llama and alpaca deaths from this problem. You need to keep vigilant with herd monitoring.

Jump to top of page

Article: Gastrointestinal Parasites in Camelids

Pamela G. Walker, DVM, MS, DipACVIM-LA

Farm Veterinarian, Alpaca Jack's Suri Farm

Assistant Professor, The Ohio State University

Internal parasites can be a problem in Camelids without appropriate monitoring. There are many different parasites that need to be considered. Parasites that we consider to be the most important in older crias through adult camelids are Strongyles (which includes Nematodirus), Trichuris (Whipworms), Capillaria, Tapeworms, Coccidians and in some parts of the country Liver flukes and Lungworms. In crias, we are concerned about Cryptosporidium, Giardia and Coccidians. This article will concentrate on adult type parasites.

There are many different Strongyle parasites and in a regular fecal floatation, the many different types can not be differentiated (with a few exceptions) and are referred to as Strongyle type of parasites. The major parasites found in the third compartment (C3 or true stomach) are Haemonchus, Trichostrongylus, Ostertagia, and three that are like Ostertagia: Camelostrongylus, Teladorsagia and Marshallagia. Small intestinal worms are Cooperia, Nematodirus, Trichostrongylus, Lamanema and Tapeworms. These parasites do not cause diarrhea, but rather weight loss, ill thrift and low protein. Many parasites are variable egg shedders; one egg found in a fecal exam may represent a significant problem. Haemonchus is known for causing severe anemia and protein loss if the infection is significant.

Whipworms, Capillaria, and Oesophagostomum are found in the cecum and large intestine. Whipwormsand Capillaria are not commonly found in fecal analysis due in part to adult parasites shedding eggs intermittently and the eggs do not float very well unless saturated sugar solution is used. Both are clinically important and resistant to treatment. The larvae initially penetrates the small intestine where they mature, then the larvae migrates to the cecum and large intestine and become adults. The adults tunnel into the intestinal mucosa traumatizing vessels causing enteritis and diarrhea.

Camelids are susceptible to several species of liver flukes with Fasciola hepatica and F. magna being the most important in the U.S., particularly in the Pacific Northwest. These parasites can cause an ill-thrift syndrome characterized by low protein and changes in blood work that indicates liver disease with specific increases in GGT concentration and Bilirubin.

Whether or not Tapeworms can cause significant disease is controversial in some circles. They also are a parasite egg not frequently found in a routine fecal float. With increasing parasite load the eggs can be found more readily, especially when using saturated sugar solution and centrifugation method. What most owners notice are those pesky looking pieces of "rice" in the dung pile - or even on occasion some very long strands of white "string". The Tapeworm (Moniezia) of ruminants is a very long worm (2 meters or more) and are passed to alpacas when they ingest contaminated forage mites. Infection tends to be one of young alpacas (weanling to yearlings) taking 6 weeks to develop to adult parasites within the alpaca with the adult worm living for approximately 3 months. Although rare, I have seen them cause clinical disease, even death from impaction in one instance.

Jump to top of page

There are several types of Eimeria species or Coccidia that can infect Camelids. These are species specific parasites with differing degree of pathogenicity. Eimeria lamae is considered to be the most pathogenic of the smaller coccidia, with Eimeria alpacae being the least pathogenic. Eimeria macusaniensis (E. mac)is the largest, slowest maturing and most significant of the coccidian parasites. For simplicity I refer to E. alpacae as small coccidia, E. lamae as medium coccidia and E. mac as large coccidia.E. mac was first reported in the United States in 1988. Like other Coccidian type parasites, it is species specific infecting alpacas as well as llamas (guanacos and vicunas). There are many differences from "regular" (small and medium) coccidia. E. mac takes longer than other coccidia for the infection to mature in the animal (time until you can find the oocyst in a fecal analysis). It also sheds for longer in the feces, greater than 45 days. The youngest it can be seen is about 45 days of age verses 21 days of age for "regular" coccidia. Although we do not currently know how prevalent E. mac is in the U.S., we do know there is widespread concern by camelid owners across the country. E. mac can be seen in all ages, with clinical disease seen more frequently in younger crias and breeding age females traveling to a new farm. If E. mac is present on a farm, herd immunity will develop in adults; leaving the younger animals the most susceptible to infection and disease. It will also expose naive animals (never exposed to E. mac before) that are new to the farm to infection with E. mac. These naïve animals should be monitored closely as serious disease (even fatalities) can occur before any clinical signs are seen. This is the primary (justified) cause of concern of camelid owners. Further complications are that clinical signs can range from no signs to severe diarrhea. Any animal that shows signs of ill thrift, weight loss, and/or diarrhea should be evaluated by your veterinarian. The first step is to run a proper fecal analysis (centrifugation using saturated sugar solution) and to determine if the protein and albumin concentrations are decreased. If you are suspicious of E. mac infection and the fecal is negative, but the protein and albumin concentration is low it is advisable to treat with Ponazuril anyway. Several factors however are encouraging, one is that immunity does appear to develop in both individuals and the herd and another is that like other coccidian parasites, healthy adults can have incidental findings of E. mac oocysts in their feces without ill effects (in my experience).

Jump to top of page

Although no formal research has been done on the best way to treat E. mac we know that Sulfas and Amprolium (Corid) only are only effective in the earliest stages of the infection. These stages are generally already past when the oocysts are found in feces. Another drug, Ponazuril (Marquis), used to treat an equine protozoal spinal parasite, has also been used to treat E. mac. The advantage of this drug is that it is effective in the later stages of the infection. Because Ponazuril is made for horses, it is too concentrated to use on alpacas as it is made. It is very water soluble and can easily be diluted. Measure out 40 grams of Ponazuril paste, using a gram scale, and then add distill water till the total weight is 60 grams and mix well; this results in a concentration of 100 mg/mL. Of this dilution, give 9 mg/lb (which equals 9 mL per 100 lbs), orally for 3 days. Since the equine paste has carrier as well as drug, this regimen should allow enough of the drug to given to be effective. Regardless of what drug is used, it is important to keep in mind that nothing stops shedding of the final stage of the parasite in feces. The importance of treating animals with clinical disease is to reduce survival of the multiplying stages of the parasite and resultant damage to the intestines.Proper monitoring of internal parasites in Camelids can be challenging, especially in larger herds. Ideally a fecal exam should be done on each animal before any de-worming drugs are administered; this can be impractical in a large herd. In small herds (equal to or less than 10 animals) all animals should be tested, in a large herd 10% of the animals or at least 10 animals should be tested. If there are several Barns, then choose 2 to 3 from each Barn with the total equaling 10 (or more if feasible). When deciding which animals to choose, pick from a variety of ages and target the ones with the lowest Body Condition Score (BCS). This should be done a minimum of two times a year. In addition, it is a good idea to perform a fecal exam on every female immediately after giving birth as her immune system is at its lowest. Another opportune time would be to test crias a few weeks after weaning. Using this information a tailored de-worming program can be designed for any size herd.

For this information to be meaningful, the correct procedure should be used. There are many different techniques and variations written about. A recent article1 compared several techniques and floatation times. The conclusion was that the centrifugation-floatation technique, using concentrated sugar (specific gravity = 1.27) and a 60 minute floatation time was superior in detecting the parasites that have the potential for causing problems in Camelids.

Jump to top of page

In addition there are techniques to give a general idea of number of parasite eggs present or a specific number of eggs present per volume of feces. The latter is preferred and this technique is called eggs per gram (EPG). Please request this method when discussing the type of fecal exam needed with your veterinarian.When discussing the results of fecal analysis, it is important to know how the numbers were obtained and what they mean. After proper preparation of the sample, each parasite egg seen on the slide is counted. As indicated previous, almost all Strongyle type parasites look very similar and are counted as a group. Nematodirus (a type of Strongyle) is a very unique egg and can and should be counted separately, especially as in some cases very low numbers of this parasite can represent a problem. Other distinctive eggs that should be counted separately are Whipworms, Capillaria, Tapeworms, and most Coccidians (especially the medium and large).

A frequently asked question is at what EPG should I de-worm my alpaca? There is not a simple answer to that question, even veterinarians cannot agree on the number! Two factors need to be taken into consideration. The first is which types of parasite eggs are found and the second is the BCS of the alpaca being tested. What is agreed upon is that if a fecal analysis reveals a significant EPG count, and the animal in question has a poor BCS, then the animal should be de-wormed. Conversely if a routine fecal analysis shows a "normal" amount of Strongyle type eggs in an alpaca that has a good BCS, de-worming is not needed or even desired. The big question is what is "normal" and what is "significant"? Truly it is a question without a definitive answer and you should work with your veterinarian to determine what is important for your herd. General guidelines for individual farms can be made after a series of fecal analysis over a period of time. If most of the time the results on your farm are less than 200 EPG of Strongyle type eggs then the de-wormer being used is still effective. If that number starts to climb, then you may have the start of a problem. The EPG number is lower when considering parasites such asWhipworms, Capillaria, Nematodirus and E. mac. It is very important to keep in mind treating the herd verses an individual animal. If you have an alpaca with a poor BCS, diarrhea, anemia and/or low protein, finding even 200 EPG of Strongyle type or 5 to 10 EPG (or less) of Whipworm, Capillaria, Nematodirus and/or E. mac will warrant treatment.

Many thought processes will need to be changed in the face of information learned by parasitologist and veterinarians over the last few years. One of the more major concepts to be changed is that alpaca owners are notorious for wanting to always have a negative fecal result in the animal being tested. Another is the desire to "rotate" drugs with each treatment.

Jump to top of page

Always having a negative fecal is a dangerous concept as it encourages the development of resistant parasites and it lowers the individual animals' immunity to parasite infection. Due to the development of resistance to current drugs used to de-worm, the strategies used to treat our animals must change. For many years parasitologist and veterinarians have recommended that all animals in a herd should be treated with a de-worming drug at the same time. This concept has proven unsustainable year after year. We are seeing that despite the supposed "cleaning" up of all the animals on a farm, there is still development of resistant parasites. The current approach is to selectively choose to treat only animals in need of treatment. This will leave a population of parasites that have not been exposed to specific drugs and will help prevent selection for resistance (term used by parasitologist is refugia). This will also take into consideration that 20-30% of animal's harbor 80% of the worms.What does this mean for the alpaca owner? Using the guidelines presented earlier, test your animals. As it is not practical to test everyone, you will have to use BCS to decide which animals to treat. The whole herd should be evaluated (preferably by the same person each time) and a chart of BCS kept. Initially treat the animals with low BCS or any alpaca that seems to be underweight for age and size. As this process continues, any animal that has a negative change in BCS should be treated (and tested). A list should be kept of those treated and if a positive weight/BCS gain in thin animals is not seen, an individual fecal in those animals should be done. It is important to also check mucous membrane color (gums, sclera, vulva) when checking BCS to determine if anemic (pale mucous membranes). Keeping in mind that thin animals with parasites may have other concurrent problems so additional testing may be necessary. Specifically, have your veterinarian perform a Complete Blood Count (CBC + PCV) to check for anemia and a Chemistry analysis to assess liver and kidney function. Further testing may be necessary in certain situations.

Rotation of drugs unfortunately does not include the use of Avermectins (Ivermectin, Dectomax) due to the presence of Parelaphostrongylus tenuis (Meningeal worm) in the Eastern United States (anywhere white tail deer are found). These drugs are still the mainstay we must use to prevent infection. Also unfortunately due to the overuse of these drugs, many of the parasites (not the Meningeal worm) have developed irreversible resistance to these drugs. In the Southern United States, this problem is very severe. De-wormers with new mechanisms of action are 5 to 7 years away from being developed in the US, so it is important to change our way of thinking.

Jump to top of page

There are 3 classes of anthelmintics in use today with small ruminants: 1) Benzimidazoles (Panacur, Valbazen), 2) Cholinergic agonists (Levamisole), and 3) Avermectins, Milbemycins (Cydectin). None of these drugs are labeled for use in camelids, so the specific doses and frequency of administration are unknown. Several of these drugs have very narrow ranges of safety. Panacur has a very wide margin of safety, whereas Valbazen and Levamisole have a very narrow safety margin. The choice of which product to use is the big question. The best choice is to use the oldest class of drugs that still results in a 90% reduction of parasite eggs found in a fecal floatation. The only way to test this is to have a fecal analysis done before any de-worming is done and to repeat (on the same animal) the fecal analysis in 14 days. If you have the room to change pastures after de-worming, wait for 4 to 5 days after the last dose of drug is given. It is also recommended that when using oral products to withhold food overnight. This slows the flow of gastrointestinal contents and allows an increase in the time the drug is in contact with the parasite. Another way to increase the efficacy of a drug that seems to be losing its potency is to repeat dosing 12 hours apart, this will also increases the duration of contact between drug and parasite (works best with Benzimidazoles). The dosing information provided should be reviewed with your veterinarian when you are considering which de-worming product to use. These are the drugs most commonly used as dewormers, other drugs may have been used in camelids, check with your veterinarian for safety..jpg)

It must be remembered that use of chemicals to control parasites is only one step in an attempt to limit parasite infection in our alpacas. Other factors such as herd density, feeding practices (always feed hay off the ground), climate, age of animal, overall health of the herd, type of soil and the actual parasites already present in the animal/environment must be taken into consideration. With so many variables, developing a proper de-worming program for your herd will not happen over night. It will take some careful thought by you and your veterinarian and a willingness to make decisions that at first seem contrary to what "you have always done".

1. Comparison of methods to detect gastrointestinal parasites in llamas and alpacas. Cebra C, Stang B. JAVMA 2008; 232 (5):733-741.

2. Anthelmintic Resistance of Gastrointestinal Parasites in Small Ruminants. Fleming S, Craig T, Kaplan R, et al. J Vet Intern Med 2006;20:435-444.

Jump to top of page

Fecal Exams:

These, ideally, should be taken from individual animals and not from a communal pooping area. This is important because it allows you to identify particular animals with problems and may show up patterns if you have a herd parasite problem. Take a latex examination glove with a little lubrication and take the feces directly from the rectum. Try to collect a good size sample - about 6-10 beans should be enough, though labs can work with less. Put it in a clean ziplock bag and clearly label with the animal's identification and the date. Take samples fresh and send away or give to your veterinarian the same day as soon as possible to prevent deterioration of the sample.

How many samples should I collect? We recommend collecting from 10% or 10 animals in your herd, whichever is the greater number. If you have fewer than 10 animals, then test them all.

Which animals? If you need to choose between animals, select those that may be a little on the skinny side and from a variety of ages. [While we're on the subject, routine body condition scoring in these heavily-fleeced animals will help you keep track of how good your feeding strategy is and also if there may be a parasite problem lurking in your herd.]

It is important that the correct procedure is performed for identifying parasites in camelid feces. Generally, camelids are a lot more susceptible to parasite problems than other species. Therefore, make sure that whoever is going to be doing your faecals knows the correct method to use. At OSU, we recommend doing a Stoll's test which involves a 1:5 dilution with a sugar solution. This is a lot more sensitive than a McMaster's which uses a 1:100 dilution and is therefore only able to pick up faecal egg counts down to 100 epg (eggs per gram). You may also conduct your own fecal tests. Please visit this site in the future to learn how.

Jump to top of page

Drugs and Doses:

Fenbendazole [eg. Panacur, Safeguard]:

Available in paste and liquid formulations generally to serve the equine and food animal markets respectively which is usually reflected in the price. Generally safe, can be used in pregnant dams and crias from a young age if required. Routine dosage: 15 to 20 mg/kg.

To figure out how much to give using the paste formulation, the weight scale on the plunger is usually based on a 5 mg/kg dosage. Therefore, multiply the animal's weight by 2 to 4 and use the dosing scale based on this. E.g. a 150 lb alpaca would receive the dose marked for a 300 (at 10 mg/kg) to 600 lb (at 20 mg/kg) horse. For the liquid formulations, this normally comes in a 10% suspension which contains 100mg/ml. Thus for a 20 mg/kg dose, you will need to give 2 ml per 10 kg (or 22 lb) or 10 ml per 50 kg (or 110 lb). In summary the range is 1 cc per 11 to 22 pounds. ( We dose 1 cc per 15 pounds ) You can use an oral dosing syringe for this or a dosing gun which normally comes with the larger packs.

Fenbendazole is available in a medicated feed formulation. This approach should only be used if you can ensure that all animals receive their prescribed dose: feeding in separate bowls may work but ensure that the animals low in the pecking order also receive theirs. Because of the higher dose recommended in camelids, animals may be required to eat more than they should and there can be the risk of grain overload.

Albendazole [eg. Valbezen]

Similar mode of action to fenbendazole but not quite as safe. Do not use in pregnant animals and use care when giving to young crias. Much better coverage for tapeworms than fenbendazole. Oral suspension.

Dosage: 10 mg/kg

Avermectins [eg. Ivomec, Dectomax]

Widely used for meningeal worm control. Meningeal worm prevention programs usually require ivermectin or doramectin to be given by injection every 30 to 45 days, respectively. Certain types of gastrointestinal parasites, such as nematodirus/whipworms/tapeworms, are highly resistant to avermectins. There not to be relied upon for control of gastrointestinal parasites. Avaiable in injectable (1% solution = 10 mg/ml), oral paste, and feed additive Dose: 300 ug/kg (1 cc of 1% injectable solution per 70 lbs body weight)

Specific Problems

To repeat, we are increasingly diagnosing resistance among intestinal parasites in llamas and alpacas. Do a follow-up fecal exam 2 weeks after treatment to confirm that the treatment has worked. A fecal egg count reduction test (checking the parasite egg count before and 14 to 21 days after deworming medication is given) allows evaluation of deworming efficacy. We expect to see >90 % egg reduction if successful. These tests can be done using the Modified Stoll's Fecal Test - this is the only tests available sensitive enough to detect the low egg counts expected after deworming.

Nematodirus or Whipworms (egtrichuris)

These parasites are notoriously variable egg shedders. Even one egg identified on a fecal exam suggests a problem. Aggressive treatment may be required. Dose fenbendazole at 20 mg/kg for five consecutive days.

Significant strongyle load

Typically, a single dose of any of the various dewormers discussed is adequate for most strongyles. Occasionally heavy burdens are seen. Treat animals for 3-5 days at 20 mg/kg dose of fenbendazole when burdens are severe or damage from larval migrations is suspected.

Moderate strongyle load

A single dose of ivermectin, fenbendazole, or albendazole may be sufficient. If the animal is severely thin, then we recommend using a 3-5 day course as discussed.

Tapeworm [eg. moniezia]

Albendazole has better efficacy for tapeworm than fenbendazole. Use a 5 day course of fenbendazole at 50 mg/kg given once daily.

Coccidia [eg. Eimeria sp.]

Coccidia are protozoan parasites. Anthelmintic drugs as discussed for intestinal parasite treatment are no effective against protozoa. Coccidia is treated with sulfa drugs (e.g. sulfadimethoxine = albon), but is prevented by using specific drugs such as amprolium (e.g. Corid) or decoquinate (e.g. Decoxx). Label directions should be closely followed because overdosing these drugs can be harmful to the animals.

* Intestinal Parasite Control Program, Camelid Health Program, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, The Ohio State University, Produced by Claire Whitehead BVM&S MRCVS and David E Anderson DVM MS DACVS

Jump to top of page

Common External Parasites

:

The most common aggravation in the barnyard, flies, seem to go hand in hand with raising animals. However there are some effective methods of control. Although primarily an annoyance, flies may cause problems such as eye irritations from feeding on tears, painful bites, and carrying disease from one animal to another. Manure removal is the most effective aspect of fly control since so many flies need manure for their eggs. A fly repellant can be most helpful on the legs of the alpaca. Disposable fly traps, although quite unsightly, can be hung around the area and can be quite effective trapping adult flies. Thousands of adult flies can be trapped per trap - and that's thousands that do not lay eggs and multiply. Natural predators can also be very beneficial in the reduction of flying critters such as flies and mosquitoes. Barn Swallows and Purple Martins both eat flying insects. It is claimed that Purple Martins eat as many as 2,000 mosquitoes a day. A bat house may also attract bats to your property which are beneficial in reducing flying insects at night. Powdered, granulated garlic can also be added to the alpaca feed to help keep the flies away from teh alpaca.

Other external parasites include mites, ticks, and lice. A mite, whose entire life cycle is spent on the animal, burrows into the outer layer of tender skin areas with thin hair coats such as the face, belly, chest, and legs causing Sarcoptic Mange. The area develops hairless spots, dandruff, scabs, and becomes crusty. It may or may not itch. As it develops, the skin becomes thick, crusty, and leather-like. Ivermectin injections are used as treatment as well as an external dousing of the area with a parasite control.

Two types of lice may infest alpacas - the biting lice and the sucking lice. The sucking lice feed entirely on blood and can cause anemia and spread disease. They prefer the head, neck and withers area where they actually imbed in the skin. Treatment is Ivomec injected 1cc/110 lbs. Biting lice nibble on hair and debris on the skin surface and can be seen with the naked eye when disrupted. They are found most often by the base of the tail or the side of the neck. Biting lice may be treated with Coral dust (also used to dust rose bushes) by parting the wool down the center of the back and pouring on the dust - about 3 Tbl. per adult alpaca or 1 Tbl./100 lbs. One method of applying the dust is to put the dosage into a mustard bottle and squeeze it out own the spine. Sevin, also a dust, is also used in the treatment of lice. If lice is diagnosed in the herd, it could be treated by putting the Seven in the alpacas dust bowls. The alpacas enjoy rolling in it and dust themselves.

Ticks can also infest alpacas, but the tick type is dependent upon the geographical area. The Rocky Mountain wood tick causing tick paralysis is not found in this Midwest area. Ticks attach to their host and feed on the blood. Remove a tick carefully and perhaps treat the bite with hydrogen peroxide.

Jump to top of page

Alpaca diseases - M. Haemolamae

One of the known alpaca diseases that you may not have heard of, but should be aware of, is Mycomplasma Haemolamae. It has been detected since the 1990's and was called Eperythrozoonosis or EPE. Recently the name has changed, but it's still the same disease. Alpaca health is very important to an alpaca business. Educating yourself about this disease will help protect your investment.

If you have an animal that is lethargic with chronic weight loss, you should consider M. Haemolamae as a possible cause.

M. Haemolamae is a bacteria that attaches itself to the red blood cells of an alpaca. The immune system recognizes this as a problem and destroys the red blood cells. Your alpaca then becomes anemic.