World Series for Sale

December 18, 2009 by Josh Deitch · Leave a Comment

What do Bud Selig, Bill Veeck, the Hot Stove, and Joseph Heller have in common? More than you might think…

The musical chairs game of Major League Baseball’s free agency has begun and already, we’ve witnessed some big names shipped to some big-name places. The New York Yankees turned Austin Jackson and Phil Coke into Curtis Granderson, allowed Hideki Matsui to sign in Anaheim, re-signed Andy Pettitte,  and have yet to decide on the future of Johnny Damon. John Lackey is now a member of the Red Sox. Cliff Lee joins Chone Figgins in Seattle. Roy Halladay replaces Lee in Philadelphia.

and have yet to decide on the future of Johnny Damon. John Lackey is now a member of the Red Sox. Cliff Lee joins Chone Figgins in Seattle. Roy Halladay replaces Lee in Philadelphia.

Does a pattern emerge here?

Once again, teams like the Kansas City Royals, the Pittsburgh Pirates, and the Washington Nationals remain conspicuously absent from the buyers’ lane. Players like Matt Holliday, Jason Bay, and Orlando Hudson remain unsigned. What are the chances that Washington makes a play for Holliday’s $10 million-plus-per-year price tag?  Holliday would lend the Nationals instant credibility, provide protection in the lineup for Ryan Zimmerman, and sell some tickets while the nation’s capital waits for the debut of Stephen Strasburg. Then again, there’s a better chance that I’d rent the movie The Last Holiday

, starring Queen Latifah, than there is that Washington would make a legitimate offer to  the Matt Holliday.

the Matt Holliday.

Everyone close to the game sits back and decries the fact that every year, the rich get richer while the poor get poorer. The competitive gap between the haves and the have-nots widens exponentially with every passing off-season. The Yankees steamrolled through October and early November 2009 propelled by the initial momentum they gained by wiping the floor with the not-quite-ready-for-primetime Twins. No matter the guts or fortitude of their opponent, the 2009 Yankees simply had too much talent.

While this collection of talent didn’t congeal overnight and New York’s success relied as heavily upon the role players and the team concept instilled by journeyman Nick Swisher and the pie-in-the-face antics of A.J. Burnett, at the end of the day, the Yankees won, because they could afford to win. C.C. Sabathia, whose salary far exceeds that of every one of his contemporaries, tossed the first pitch of the World Series. The final pitch of the World Series was thrown by the highest paid closer in the game, picked up by one of the highest paid second basemen in the league, thrown to the league’s highest paid first baseman, and backed up by one of the game’s highest paid catchers.

However, many baseball fans examine the facts above, freak out; declare that the Yankees buy championships; and determine that they ruin baseball’s competitive balance. Then these same people run out and buy a bright pink Red Sox hat. It’s not that simple. The Yankees are far from the cause of the competitive imbalance that plagues today’s game. In fact, they’re simply the biggest symptom of a problem far more inherent and deep-seeded in Major League Baseball.

The major issue in question is the conspicuous absence of a genuine salary cap and a comprehensive system of revenue sharing. Take a look around. The NFL is undeniably the most profitable and entertaining professional sport. By using a strict salary cap, non-guaranteed contracts, and a system of revenue sharing that ensures the success of most teams in the league, the NFL has grown into a multi-billion dollar industry, while simultaneously ensuring that its teams are generally on an even playing field.

Conversely, baseball, more than any other professional sport, suffers from the shortsightedness and greed of its governing bodies. The majority of baseball owners invest in teams not to put an exciting and competitive product on the field, but to line their own pockets. Owners like the late Bill Veeck, who went bankrupt on a number of occasions trying to entertain his viewing audience and win a championship, are rare commodities. Instead, fans in Pittsburgh, Cleveland, or Kansas City are forced to watch last place teams, despite their franchises receiving basically free money in luxury tax payments and television-generated revenue.

In sports, the division between the first and second division, should never be financial. It should always be decided on the field, during the season, not in some conference room in late December. However, until baseball has a commissioner willing to take a stand against the greedy owners, whose best interests—according to Veeck—never coincide with the best interests of the game, and to battle the unreasonably powerful players’ union, we’ll never see the competitive balance in baseball restored.

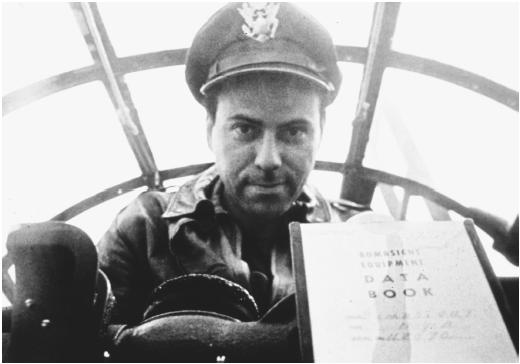

Joseph Heller’s comedic masterpiece, Catch-22

, is named after the conundrum that pilots during World  War II generally did not want to fly in missions, because they feared being shot down. However, in order to avoid a mission, a pilot had to prove that he was insane. By regulations, the only way to judge sanity was based on a person’s sense of self-preservation. Simply, if a pilot didn’t want to fly, then he wanted to live, and thus he was of a sound mind, and had to fly.

War II generally did not want to fly in missions, because they feared being shot down. However, in order to avoid a mission, a pilot had to prove that he was insane. By regulations, the only way to judge sanity was based on a person’s sense of self-preservation. Simply, if a pilot didn’t want to fly, then he wanted to live, and thus he was of a sound mind, and had to fly.

Welcome to baseball economics, as written by Joseph Heller. Owners unwilling to pay the exorbitant prices for star players demand a salary cap in order to return baseball’s competitive balance. However, at the same time, these same owners don’t want a salary cap, because a limit on payroll also means that there must exist a payroll minimum. Thus, cash-conscious owners will never allow the implementation of the very limitations that they demand.

Would anyone be surprised if it eventually came out that no one would be able to meet with Bud Selig while he’s in his office, a la Major Major? Instead, interested parties would be greeted by his receptionist, who would then alert Selig to their presence, allow him time to climb out the window, and then show them into his office.

Ultimately, like Heller’s Yossarian, baseball fans are stuck flying an unending string of missions with no logical or illogical way out.

Until something really changes, we’re only left with one question:

Who’s going to buy the next World Series title?