A Small Town Tale: Phil Paine

April 17, 2010 by Chip Greene · 8 Comments

When he was six or seven years old, my grandfather, Nelson Greene, who grew up to briefly pitch in the major leagues for the Brooklyn Dodgers, moved with his family from the Philadelphia suburb of Roxborough, to the small town of Lebanon, Pennsylvania. For the rest of his life, despite long periods of absence, Nelson called the small town his home. Today, it is his final resting place.

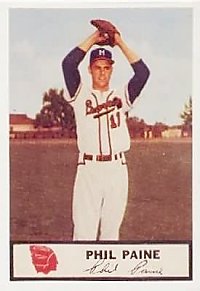

Less than 20 miles west of Lebanon is the even smaller town of Hummelstown. Given its close proximity to Lebanon, it’s easy to envision that Nelson must have passed through Hummelstown at least once or twice during his life. If he did, perhaps he stopped into the Warwick Hotel; and if he did, perhaps he also met the Warwick’s proprietor, Phil Paine. Paine wouldn’t have been hard to miss: on the west wall of the Hotel’s main barroom was an enlarged replica of Paine’s St. Louis Cardinal’s baseball card. Nelson and Paine would have had much in common to talk about. (Refer to Nelson’s biography at the SABR BioProject website to see just how similar were their careers.)

Growing up, I often visited my grandfather in Lebanon, and over the years, I developed somewhat of an affection for the town. If I ever heard of Hummelstown over the years, I don’t remember. I do know, however, that until several months ago I had never heard of Phil Paine. But one day while searching a list of players to research, I came across Paine’s name, and much to my curiosity noticed that he had died in Lebanon. I was fascinated to discover the connection, wondered how it had come to pass, and I had to know Paine’s story.

Here it is.

*****

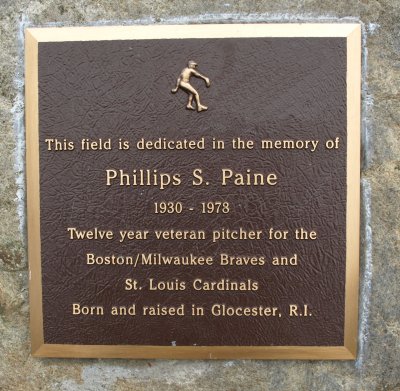

Tucked in the northwest corner of Rhode Island, just ten miles from both Massachusetts and Connecticut, in the town of Glocester, is the village of Chepachet, where Phillips Steere Paine was born on June 8, 1930. When Paine was a teenager in the 1940s Chepachet didn’t have its own secondary school, so each school day Paine traveled roughly five miles north to the village of Burrillville to attend high school. To this day, Phil Paine is the only player from Burrillville High School ever to play baseball in the major leagues.

Over parts of six seasons, playing with the Braves both in Boston and Milwaukee, and also with the St. Louis Cardinals, Paine, a tall (6’2â€), slender (180 pounds) right-handed pitcher, totaled 150 innings in 95 games, all in relief. After appearing in his first game at age 21, his major league career was ended before he turned 30, but during that time he amassed a sparkling career record of 10-1, a .909 winning percentage, and also served his country in the Korean conflict, before finally settling down with his family to a quiet small town life as the proprietor of a hotel. Much like his baseball career, Paine’s life, too, was ended far too soon, but as his family noted at Paine’s memorial service, “he accomplished all that he wanted to do.†For a young man from a place as tiny as Chepachet it surely must have been an exhilarating journey; and as his sister Marcia told me, “Phil loved every minute of it.â€

Over parts of six seasons, playing with the Braves both in Boston and Milwaukee, and also with the St. Louis Cardinals, Paine, a tall (6’2â€), slender (180 pounds) right-handed pitcher, totaled 150 innings in 95 games, all in relief. After appearing in his first game at age 21, his major league career was ended before he turned 30, but during that time he amassed a sparkling career record of 10-1, a .909 winning percentage, and also served his country in the Korean conflict, before finally settling down with his family to a quiet small town life as the proprietor of a hotel. Much like his baseball career, Paine’s life, too, was ended far too soon, but as his family noted at Paine’s memorial service, “he accomplished all that he wanted to do.†For a young man from a place as tiny as Chepachet it surely must have been an exhilarating journey; and as his sister Marcia told me, “Phil loved every minute of it.â€

He was the only son and eldest of three children born to Arthur and Celia Paine, and he was named Phillips after Arthur’s best friend. The elder Paine had himself been a ballplayer, and from the time her brother was three years old, Marcia remembered, “Phil had a glove in his hand.†In fact, Marcia continued, Phil and Arthur were often opponents on local teams, although she couldn’t recall which ones. 1

Beyond sports, Arthur Paine was also an avid outdoorsman who loved hunting and fishing, and Phil inherited from his father that same lifelong love of the outdoors. One of Phil’s Burrillville High School teammates, George Ducharme, now 80 years old, shared with me his recollections of accompanying Phil on several of Paine’s hunting excursions; George never carried a gun, but he enjoyed walking along as Paine regaled him with stories. So fond was Paine of the outdoors, in fact, recounted Ducharme, one day during the boys’ senior year, on the first day of fishing season, Phil skipped baseball practice to go fishing and was summarily benched for one game by his coach. When I shared that story with Marcia and asked if that sounded like something her brother would do, she replied, “Sure, if he wanted to (fish) bad enough.†But Phil, Marcia continued, could have missed a lot of practices and it wouldn’t have made much difference; he was just naturally that good, she proudly boasted.

Indeed, he must have been. In 2002, Paine was posthumously inducted into the second-ever class of the Burrillville High School Athletic Hall of Fame. 2 In addition to his baseball exploits (he played varsity for four years), Paine was also a goaltender for three years on the hockey team; during his senior season, the hockey team was undefeated in league play. On the mound, Paine led the Broncos to four Western Division league championships, and as a senior was named to the All-Class C First Team. 3

That year, 1948, was a singular season. In addition to Paine’s individual accomplishments, the Broncos were not only Class C league champions but also won the state championship, as Paine outpitched his more heralded rival, Chet Nichols (whom Paine would later join on the Braves) in a thrilling 3-2, extra-inning victory over Pawtucket East, in a game played at Brown University. (“Oh, that Nichols was a ‘hot head’,†recalled Marcia, who knew Nichols. “He was so mad when Phil beat him.â€) On that day scouts were out in droves, “mostly to see Nichols,†recalled George Ducharme, who captained the team and played in that game, “but after the game I saw Phil talking to some scouts.†Soon thereafter Paine signed a contract with the Philadelphia Phillies, and his professional baseball career began.

That summer, Paine joined the Phillies’ Class D entry in the Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York (PONY) League, the Bradford (PA) Blue Wings. In 12 games, the 18 year old acquitted himself nicely. Making 8 starts and tossing 97 innings, Paine recorded a 5-4 record with an impressive 2.41 ERA, although, not for the last time, he struggled with his control, finishing with a strikeout to walk ratio of just 35/32. Perhaps due to his youth, and despite his low ERA, Paine also proved somewhat inconsistent: while he pitched a 10-0 shutout late in the season to give Bradford a fourth-place finish in the final standings, he was later shelled in a September 13 playoff loss to the Lockport Reds, surrendering 8 runs and 15 hits before being pulled in the top of the seventh inning.

Nonetheless, Paine showed much promise, and when the 1949 season opened he had earned a promotion. Beginning the season at Toronto, in the AAA International League, the right-hander had a brief tryout there in two games before settling in for the remainder of the season at Vandergrift (PA), the Phillies’ team in the Class C Middle Atlantic League. Once again a starter, Paine hurled 202 innings in 35 games but his ERA ballooned to 5.48, as he was again victimized by a lack of control: 136 walks–an average of 6.1 per 9 innings.

As it turned out, that was his final season in the Philadelphia organization. On the advice of a scout named Jeff Jones, who was in charge of the New England area and had signed Chet Nichols to a contract, on December 6, 1949, the Boston Braves drafted Paine from the Phillies’ organization. Within a year and a half the Rhode Island native was pitching in front of the Boston fans just 65 miles from his home town.

Paine arrived in the major leagues via a timely sequence of events. In 1950, the right-hander spent the entire season with the Hartford Chiefs, the Braves’ Class A team in the Eastern League. Pitching strictly in relief, Paine appeared in 30 games, posted an 8-3 record and 3.12 ERA, and, perhaps most importantly, reduced his walks per 9 innings to 3.1. It was a solid performance and earned the right-hander a scheduled promotion to AA, where the Braves intended he would start the 1951 season with the Atlanta Crackers, in the Southern Association.

But that’s when chance intervened. Prior to the start of the season Paine had learned that in May he was to be inducted into the Army. Therefore, rather than reporting to Atlanta, Paine asked the Braves’ management to return him to Hartford so that he would be closer to home when the time came for his call to service. That spring Hartford had undergone a managerial change: when Ripper Collins, who became the Chief’s manager in 1949, resigned to take a position as a radio announcer, he was replaced by Tommy Holmes, who agreed to serve as player-manager of the Chiefs.

Holmes was impressed with the tall right-hander. Paine “came to me this spring,†the manager recalled that summer about the pitcher’s performance at Hartford, “and told me he felt he could start games as well as pitch in relief. I tried him as a starter and he won four of his first five for me. Showed me he could go the distance, too.â€

As May passed without Paine receiving his draft notice, he remained with Hartford into the summer of 1951, working both as a starter and in relief. By July 4, he had appeared in 17 games, made 7 starts, and worked a total of 72 innings, amassing a record of 6-6 with a 3.50 ERA. Yet he again suffered bouts of wildness, as his average walks increased to 5 per 9 innings.

In the meantime, there was a managerial change in Boston. On June 19, citing ill health, Braves’ manager Billy Southworth suddenly resigned, and Holmes was asked to move to the major league level and take over the struggling ball club. On July 4, in one of the first personnel moves of Holmes’s tenure, the Braves assigned reserve infielder Gene Mauch and pitcher Sid Schact to their American Association club in Milwaukee and called-up to the major league club shortstop Johnny Logan from Milwaukee and Paine. After just 96 games in the minor leagues, the 21-year old from Chepachet was going to the majors.

Understandably, he was excited to join the Braves. “If I’d gone to Atlanta,†Paine told the press upon his arrival, “this probably wouldn’t have happened for a couple of more years. So Uncle Sam has done me a favor up to here,†he continued, referring to his delay in being drafted.

“They told me there was a telegram for me in the Hartford clubhouse and everyone started congratulating me. I thought they were kidding. I thought it was from the draft board. I nearly fell over when I read it and found out I’d been called up to the Braves.†4

For his part, Holmes was glad to add Paine to the Braves’ pitching staff. Having watched the right-hander perform in those 17 games at Hartford, the new Boston manager was aware of Paine’s skills and was impressed not just with the pitcher’s physical ability, but also with his demeanor.

“This kid has got a lot of stuff,†Holmes explained to the press. “Plenty of poise and a great attitude. He’ll be the tenth pitcher. There won’t be any pressure on him. But we might as well have him up here and sweat him out in the big league [ sic ]. I know he’s going to make the grade and we’ll find enough work for him to do so there won’t be any chance for him to rust on the bench.â€

Paine’s addition to the Braves created a unique circumstance: Fellow pitchers Max Surkont, who joined the team in 1950, had been born in Central Falls, Rhode Island; and Chet Nichols, who was in his rookie season, hailed from Pawtucket. Both men were already on the team when Paine arrived, and the triumvirate marked the first time since before the turn of the century that three native Rhode Islanders played on the same major league team. Together, the three posted a record that year of 25-24 for Boston, which finished the season with a record of 76-78.

Ten days passed before Paine got into his first game. Finally, on July 14, at home versus the Cincinnati Reds, he made his first major league appearance. Although the Braves were shut out by Cincinnati for the second consecutive game, 5-0, Paine, wrote the press, “made an impressive major league pitching debut for the Braves, striking out four of the six batters who faced him in the last two innings.†Nine days later, in a 15-14 Braves win over Pittsburgh, Paine, the third of five Boston pitchers, then collected his first career win, as he allowed three hits in two innings. By season’s end Paine had logged 35 1/3 innings in 21 games, won 2 without a loss, and posted a 3.06 ERA, and if his walks remained problematic (he issued 20 with only 17 strikeouts), still, he had proven effective. But that fall Paine was finally drafted into the Army, and it would be two long years before he again took the mound for the Braves. When he did, the team no longer called Boston its home.

For the next two years, despite his military obligations, Paine continued to play ball both at home and away. Yet during that time he also experienced the most significant event of his life. As 1952 began, prior to being sent overseas, Paine was sent for basic training to Indiantown Gap Military Post, in Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, where he remained for the next 11 months. Anxious to stay in shape, on the weekends Paine played for the nearby town of Hummelstown, in the City Twilight League, and also for Palmyra, in the Lebanon County League. During off hours the soldiers often spent their free time at one of their favoring watering holes, the Warwick Hotel and Restaurant, in Hummelstown, and there Paine met a young lady named Jeannette Orsini, whose father owned the inn. Soon, Phil and Jeannette began a courtship, and when Paine was subsequently sent to Japan, he regularly corresponded with Jeannette. In December 1953, following Paine’s discharge, the two were married; it was a union that lasted 25 years, until Paine’s death, and produced three children: sons Dan and Jeff and daughter Sherri, and also eventually four grandchildren. After his marriage, Paine forever after called Hummelstown his home.

With basic training completed, Private First Class Paine was assigned to the Fifth Infantry division and soon sent to the U.S. Army Personnel Center at Camp Drake, in Fukuoka, Japan. In his official duty as a cadreman Paine was already at Camp Drake when George Ducharme, his old high school teammate, later arrived. Ducharme shared with me a very personal story.

“You can use this story or not,†offered Ducharme when we spoke by phone one Saturday afternoon, “but it’s very personal to me and I’d like to tell you about it if you’re interested. “ When I assured him I was, he began his story.

Upon graduation from Burrillville High School, Paine, of course, was drafted by Philadelphia, while Ducharme was given a scholarship to attend Providence College and play baseball. When Ducharme was later drafted into the Army, he, too, was sent to Camp Drake and was reunited with Paine. At the time, Camp Drake was an athletic powerhouse among the various service branches, and Paine was the star pitcher on the Drake baseball team. When Ducharme arrived, Paine told the Drake coaches about his former teammate’s baseball talents and recommended that Ducharme be assigned to the team. Subsequently, Ducharme’s unit was deployed to Korea, but as a member of the baseball team Ducharme remained behind. Sadly, all but seven or eight of Ducharme’s unit were eventually killed in the fighting, he explained, “but because Phil Paine got me on the team, I survived and was able to live the life I have led. I’ll always be grateful to Paine for that. Without him, I probably would have been killed with the rest of my unit.â€

I thanked Mr. Ducharme sincerely for his very poignant tale. 5

Throughout 1953, Paine remained at Camp Drake. According to Mr. Ducharme, as the new soldiers arrived at the camp, Paine was responsible for greeting them and arranging for their lodging. “It wasn’t bad duty,†Paine himself later remembered. Most importantly, it gave him the chance to continue with his civilian profession.

While at Camp Drake, Paine signed with the Nishitetsu Lions, of the Japanese Pacific Coast League. During his days off from duty the right-hander pitched twice a week for the Lions for a salary of $575 per game. The extra money undoubtedly came in handy as a supplement to Paine’s military pay, and when he returned to the states he recalled for the press that “It turned out I was a pretty soft touch for a loan when my buddies ran short before payday. And some of them,†Paine further related, “had short memories when it came to paying me back.†In 9 games for the Lions, a total of 61 innings pitched, Paine compiled a 4-3 record and 1.77 ERA. Finally, in November 1953, Paine was discharged, and he returned to the United States to resume his major league career.

By the time Paine reported to spring training in Bradenton, Florida, to begin the 1954 season, the Braves had relocated to Milwaukee. During the previous season, Braves’ pitching coach Bucky Walters, anticipating Paine’s return to the mound in ’54, had noted to the press that “Phil could very well turn out to be a great addition to our staff when he is discharged from the service. He has all the necessary equipment to be a top notch pitcher.†In particular, noted Walters, Paine, who threw side-arm, possessed an effective sinker and curve (he also threw an effective change-up), which made him an ideal candidate for a relief role. His development, it was hoped, would allow Paine to anchor manager Charlie Grimm’s overhauled bullpen in 1954. Unfortunately, though, things didn’t quite work out as planned.

Once again, Paine simply couldn’t find the plate, although perhaps he wasn’t given much of a chance to prove himself. Whether Grimm lacked confidence in Paine or the right-hander had some undisclosed injury is unclear. Regardless, following a brief outing on July 18, Paine had appeared in only 11 games and pitched a total of just 14 innings on the season; yet during that time he issued 12 walks, a hefty average of 7.7 per 9 innings. On May 22, in Chicago, he was credited with his third career win (without a loss) in an eventual 11-9 Milwaukee victory, but beyond that appearance there were few additional highlights. Still, when the Braves purchased veteran left-hander Dave Koslo from their Toledo (AAA) farm club on July 19 and assigned Paine to the same team, the assignment struck some observers as somewhat of a “surprise move.†But it was a clear signal that Paine’s future with the Braves was anything but secure.

In the spring of 1955 Paine failed to make the Braves’ team. On April 5, management optioned him to the AA Atlanta Crackers, where they had intended to send him back in 1951. His stay there was brief, however. Although the right-hander posted a record of 2-0, his all-too-familiar struggles with control once again predominated, as he walked 19 batters in just 23 innings; those walks undoubtedly were directly responsible for his 5.87 ERA. Soon, after just a month in Atlanta (seven relief appearances), Paine was reassigned to Beaumont, in the Texas League. There, in sweltering summer heat, the Rhode Islander pitched well enough to earn a return to the major leagues.

When Paine arrived in Beaumont early in May, he joined a team that was battling to stay out of last place. Desperately in need of pitching, the Exporters immediately installed Paine as a starter and the right-hander responded with one of the best stretches of pitching in his career. Inexplicably, he once again harnessed his control, and the results were impressive: appearing in a total of 15 games, Paine started 14 of those and completed 7, including a 2-hit shutout in a 5-0 defeat of Fort Worth on June 21. With a .500 record in 12 decisions for a sub-.500 team, Paine struck out 95 batters in 118 innings; most importantly, though, he walked just 42, an average of 3.2 per 9 innings. It was the best control he’d exhibited since his first professional season, and the Braves took notice. On July 6, when pitcher Joey Jay was sent to Toledo following the completion of his two year roster requirement as a bonus player, Paine was recalled to Milwaukee to replace him.

Yet it was bound to be his final opportunity. If he could just throw strikes consistently, perhaps Paine would finally find a permanent home in the Braves’ bullpen. Indeed, one headline said it all: ‘Phil Paine, Fugitive From Beaumont’s Heat, Hopes Milwaukee Will Be His Lasting Address.’

Ironically, it may have been the heat that provided the New Englander with another chance- and this time, he pitched like it would be his last. Following one of the best performances of his major league career, a four-inning stint at Brooklyn on August 2 during which he allowed just 1 hit and struck out 6 to earn his fourth career win, Paine had allowed just 3 hits and struck out 13 in 9 1/3 innings since his recall (5 games); with only one earned run allowed, his ERA was 0.96. He had never pitched better.

After that game, Paine explained to the press that, “I came out of the army overweight. I lost my sinker, one of my best pitches, in the service. Then the trip to Beaumont melted off the extra weight. †In the broiling Texas heat, he continued, “I lost 17 pounds down there in about five weeks. I lost about 10 pounds a game, even in night games.†Now, Paine concluded, “I can get my curve ball over the plate and my sinker is working again.â€

Long time coach Johnny Cooney, who had watched Paine throughout his Braves’ career, concurred that the right-hander’s performance was much improved.

“Phil … came up to us at Boston in 1952,†Cooney told the press following Paine’s August 2 win, “as (one) of the best rookies in the organization. Tonight, for the first time since Phil got out of the army, he looked more like his old self. He’s got a side arm curve and sinker, his best pitches, again.â€It was perhaps Paine’s most effective performance. Although he ended the season with only 25 1/3 innings pitched in 15 games, Paine struck out 26 and limited his walks to 14, with an impressive 2.49 ERA. Moreover, he won two games without a loss, and his career record now stood at 5-0. Yet despite that performance, as things turned out, it wasn’t enough; with the exception of two appearances over the next two seasons, 1955 effectively marked the end of Paine’s Braves’ career.

For the next two seasons he toiled almost exclusively in the minors. After making the team in the spring of 1956, Paine had appeared in just one game when the Braves agreed to option him outside the organization. Wichita, the Braves team in the AAA American Association, was interested in purchasing first baseman Don Bollweg from the Minneapolis Millers, the New York Giants entry in the same league; but by all accounts, Minneapolis wanted a player in return. Accordingly, on May 10, the Braves optioned Paine to Minneapolis to complete the deal. In 58 games, including 5 starts, Paine won 8 and pitched 116 innings, while issuing 4.3 walks per 9 innings. On August 29, he was recalled to Milwaukee but instructed not to report until the following spring; on September 18, he surrendered a game-winning home run to Indianapolis’s Joe Altobelli in Minneapolis’s four games to three playoff loss; and finally, on October 12, Paine was reassigned outright to Wichita. 6 As he returned to Hummelstown in the fall of 1956, the right-hander’s immediate future in the major leagues was certainly in doubt.

The following spring provided little reassurance. In 1957, the year Milwaukee went on to win the World Series, Paine failed to make the team in training camp. Instead, in April, he reported to Wichita—and surprisingly produced a season that gave Milwaukee one final reason to send him to the mound. In 52 games, all but three in relief, Paine posted a 1.64 ERA in 104 innings pitched, while walking a career-low average of just 2.9 batters per 9 innings. On September 7, Paine was subsequently recalled to Milwaukee (although too late to be eligible for the World Series), and one week later, at home against Brooklyn, he allowed just one hit in two innings of work (although, perhaps fittingly, he walked three) and held the Dodgers scoreless. Yet it turned out to be his final regular season appearance in a Braves’ uniform. 7

Paine attended his last Milwaukee spring training in 1958. By then, in the estimation of manager Fred Haney, the pitcher was one of several who were “on the fringeâ€; and, exclaimed Haney, “it will be up to them to make [me] keep them around.†In the end, Paine wasn’t kept.

On April 15, 1958, Milwaukee asked waivers on the right-hander; four days later he was awarded to St. Louis for $20,000.

To the Cardinals, he wasn’t an unknown commodity. During Paine’s season at Wichita, “we got a real good report on him from our Omaha manager, Johnny Keane,†Cardinals’ pitching coach Al Hollingsworth related to the press in July. Following that season Paine had also played winter baseball for the first time as a member of the Estrellas de Oriente team in the Dominican League, where Hollingsworth was a manager, and the Cardinals’ coach had gotten “a good chance to see (Paine) work.†So when the right-hander later became available, Hollingsworth explained, “Keane and I recommended his purchase as strongly as we could.â€

Hollingsworth saw in Paine the same assets that had long enamored the Braves. “There are a lot of pitchers much faster than Phil,†the pitching coach opined, “but he’s learned control, has a good sidearm curve that he keeps low and I’ve yet to see him get excited even when he goes out there with the bases full and no outs.†In short order, Paine became a workhorse out of the Cardinals’ bullpen.

That season, Paine pitched his final 46 major league games. He got off to a torrid start. On June 24, in Pittsburgh, he won his fourth consecutive game for the Cardinals, lowering his season’s ERA to 0.79 and raising his career record to 9-0. By September, though, Paine had clearly tired and he split two more decisions, finishing the year with a 5-1 record in 73 1/3 innings and an ERA of 3.56. It had been a productive performance, but little could Paine have guessed that he had thrown his final major league innings.

Following the season Paine joined 19 of his teammates in a month-long exhibition tour of the Pacific. After departing on October 9 (the next day he was reassigned outright to Wichita), the team played 16 games: three in Hawaii; one each in Manila, Okinawa and Korea; and the final ten at various stops in Japan. During the tour Paine won two games for St. Louis and also visited Camp Drake, where he renewed old friendships and also spoke at a luncheon held in his honor at the Camp Drake Non-Commissioned Officer’s Club. And while he was in Japan Paine was also offered another contract by the Nishitetsu Lions, an offer in which, he told the press upon his return to the States, the right-hander was “definitely interested.†Although Paine ultimately refused the offer, it wasn’t the last one he received.

On December 4, 1958, Paine’s brief Cardinals’ career was ended. That day, St. Louis traded outfielder Wally Moon to the Los Angeles Dodgers in exchange for outfielder Gino Cimoli, and as a part of the deal the Cardinals sent Paine to the Dodgers farm club in Spokane, Washington. Four days later the press announced that Paine had sent a telegram to the Kinletsu Pearls, in the Japanese League, agreeing to play for them in 1959, but on December 14 Paine vigorously denied the report, although he again admitted he was seriously considering overtures from Japan.

If Paine was torn between where to play, he had a good reason to give the majors another try: as the year began, he needed only 16 days of major league service to qualify for his pension. Therefore, in January, Paine told the press that he had notified Kinletsu he would not be joining the team after all. He qualified that decision, however, by further stating that if he “fail[ed] to stick in the majors this year,†he would accept an offer to pitch in Japan in 1960.

In February, 1959, Paine joined the Dodgers at spring training in Vero Beach, Florida. There, he further elaborated about his offers from Japan. “I had a big offer from Osaka this year,†Paine explained to reporters, “about double my present salary.†Yet after discussing the offer with his family, he continued, Paine had decided instead to remain in the United States.

And that ended his deliberations with the Japanese.

Yet there would be no more major league appearances. Paine never made the Dodgers squad in 1959; unfortunately, the club was loaded with pitching talent and he spent the entire season in Spokane. But in December, Paine was one of three players included in a deal that sent him to Vancouver, a Baltimore Orioles farm club, and for the next two seasons, the final of his career, Paine appeared in a total of 116 games for the Mounties, all but one in relief. Then, following the 1961 season, Paine retired at the age of 31.

For the remainder of his life Paine ran the family inn, the Warwick Hotel and Restaurant, in his adopted hometown of Hummelstown; perhaps wary of his baseball future, at some point he and Jeannette had purchased the Warwick from his in-laws. Over the years the right-hander coached both Little League and American Legion ball, and by all accounts he led a quite contented life. Sadly, however, on February 19, 1978, at just 47 years old, the right-hander succumbed to a brain tumor and passed away at the Veterans Hospital in the nearby town of Lebanon. He was laid to rest at the Hummelstown Cemetery.

For the remainder of his life Paine ran the family inn, the Warwick Hotel and Restaurant, in his adopted hometown of Hummelstown; perhaps wary of his baseball future, at some point he and Jeannette had purchased the Warwick from his in-laws. Over the years the right-hander coached both Little League and American Legion ball, and by all accounts he led a quite contented life. Sadly, however, on February 19, 1978, at just 47 years old, the right-hander succumbed to a brain tumor and passed away at the Veterans Hospital in the nearby town of Lebanon. He was laid to rest at the Hummelstown Cemetery.

After a life fulfilled, Phil Paine received one final tribute: on May 10, 1997, in his hometown of Chepachet, one of two new baseball fields at the new Glocester Memorial Park was dedicated in his memory. It was quite an accomplishment for the tall right-hander who had ascended from a tiny Rhode Island town to reach the highest level of his sport.

[1] George Ducharme, a high school teammate of Phil, told me he vaguely remembered the elder Paine, whom he referred to as ‘Dan’, as a 45-year old spitball pitcher in a Sunday league.

[2] In 1979, the first Phillips Steere Paine Memorial Plaque was presented in Paine’s memory to a Burrillville High School athlete in recognition of “athletic ability, team spirit and sportsmanship.â€

[3] According to Marcia, Paine acquired his nickname, ‘Flip’, from a Burrillville teammate.

[4] Following the season, Paine was honored in Chepachet with a testimonial banquet, where he was presented with a wrist watch.

[5] Mr. Ducharme told me that during Paine’s induction into the Burrillville Hall of Fame, he met Paine’s widow and family and had the opportunity to share this story with them.

[6] There is some discrepancy in the reporting of Paine’s return to Wichita. In his Hall of Fame file it is noted among his transactions that Paine was assigned outright on October 12. On October 13, however, a brief AP story reported that “[t]he Wichita Braves announced that Everette Joyner, OF, has been traded to the Milwaukee Braves for three players… Phil Paine (Minneapolis, American Association) and Jack Hannah (Jacksonville, SAL), pitchers, and Tobey Atwell (Miami, IL), catcher.†Regardless of the official transaction, as 1956 came to a close, Paine had rejoined Wichita.

[7] Although Paine was not on the Braves’ World Series roster, he nevertheless supported the team. His sister Marcia lived with Phil and Jeannette in Milwaukee during those days and got to know many of the players. One day several years ago, she related, Marcia was watching a documentary about Hank Aaron, whom she had known back then, and a segment aired from an interview Aaron gave during the ’57 World Series. She was never so surprised as when a player crossed the camera behind Aaron: it was her brother. Marcia laughed with pleasure when she related that story to me.

SOURCES

- Phil Paine player file- National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY

- Biographical sketch provided by Mrs. Phil Paine

Interviews

- My sincerest appreciation to Mrs. Jeanette Paine, widow of Phi Paine, who sent me several biographical documents related to her husband.

- My sincerest appreciation as well to Mrs. Marcia Eddy, Phil Paine’s sister, with whom I spoke by phone on March 13, 2010.

- Personal interview by phone with Mr. George Ducharme, a high school teammate of Phil Paine, on March 6, 2010.

- Personal interview by phone with Mr. Jeff Farrell, who heads the Burrillville High School Hall of Fame Committee, on March 9, 2010.

Newspapers

The Era (Bradford, PA)

Gazette and Bulletin (Williamsport, PA)

(AP) Morning Herald (Hagerstown, MD)

Nashua (NH) Telegraph

(UPI) The Independent (Long Beach, CA)

(AP) Titusville (PA) Herald

(UPI) Waukesha Daily Freeman (WI)

(AP) Manitowoc Herald Times (WI)

(UPI) Janesville Daily Gazette

(UPI) The Brownsville Herald (TX)

(AP) Hutchinson(KS) News-Herald

(AP) Lowell (MA) Sun

Pacific Stars and Stripes

(UPI) Appeal Democrat (Marysville, CA)

Independent (Long Beach, CA)

(AP) Port Angeles Evening News (WA)

(AP) Charleston (WV) Gazette

Sunday Patriot-News (Harrisburg, PA)

The Woonsocket (RI) Call

Websites

- www.japanesebaseballdaily.com/foreignpitching

- www.retrosheet.org

- www.baseball-reference.com

- www.baseball-reference.com/minors

- SABR Baseball Biography Project- Tommy Holmes, www.bioproj.sabr.org-

Very well researched. Excellent article. I Remember having his 1958 Topps baseball card when I was a kid.

Very interesting story. As a child, my dad used to watch Phil pitch to the village (Chepachet, RI) kids behind the local elementary school. My dad showed me the school and his boyhood home this past summer. As a Pennsy resident, my next stop will be the Warwick.

This is a wonderful article about my father,,,,well researched an true,,,some of the things in the article filled some gaps that i didn’t know of..

I had the opportunity to see Phil Pain pitch several games at Capilano Stadium in Vancouver during the 1960 and 61 seasons. Phil pitched out of the bullpen for both managers George Staller and Billy Hitchcock. During the 1960 season Phil was reunited with a former teammate on the Milwaukee Braves Chet Nichols.Great article on Phil, I sure enjoyed it.

Barry

I have visited the PhilPaine ballfield in Chepachet; and have always been impriessed with his 10-1 record. If he was good enough to get such a wonderful record, why wasn’t he used more? And if he wasn’t good, how did he get a 10-1 mark? Puzzlement.

I was aware of the “three Rhod Island right handers on the 1952 Braves, and was pleasantly surprised to see it again in print. SawNicholspitch against Jack McKinnon of La Salle at McCoy Stadium. McKinnon signed with theDodgers and went to Pueble.

This is a very well written and exhaustively researched article. Congratu-lations. I am trying to get published a New England Sports Calendar, and have alreqady inluded PhilPaine in my first draft.

(Fr. Gerald Beirne (SABR) Narragansett RI

My name is also Philip Pane. I was at the Polo Grounds in the 50’s and saw Phil Paine pitch against the GIants. he came in to pitch with the bases loaded in a tie game.and threw a wild pitch to end the game. I was very upset.

My name is Brian Loynds and I am currently the head baseball coach at Burrillville High School, I enjoyed reading about Mr Paine and his life story. I wonder if you could assist me with contacting his family? Interesting fact – my son who played for Burrillville High School baseball from 2013 – 2016 received the Philip Paine award in 2016 – small world. Thank you again – Brian Loynds