Black Ball, Both Real and Imaginary

August 30, 2010 by Jeff Polman · 2 Comments

I’ve never been a huge fan of baseball fiction. The game’s natural mythology and unforgettable luminaries since the turn of last century is so rich and entertaining by itself that I never felt a need to delve into stories and characters separate from the real ones. I did make an exception for W. P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe , which took historical fact and beautifully merged it with a dreamy present, before going on to spawn an even more incredible feat—producing a timeless Kevin Costner movie.

Well, Exception No. 2 has arrived, forever claiming a lordly spot at the top of my baseball bookshelf. Peter Schilling Jr.’s The End of Baseball

(Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, $14.95) is an absolute marvel, a funny, heartbreaking, poetically written yarn that takes a little-known baseball fact and transforms it into something magical, profound, and unforgettable.

Well, Exception No. 2 has arrived, forever claiming a lordly spot at the top of my baseball bookshelf. Peter Schilling Jr.’s The End of Baseball

(Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, $14.95) is an absolute marvel, a funny, heartbreaking, poetically written yarn that takes a little-known baseball fact and transforms it into something magical, profound, and unforgettable.

Back in 1942, before he went off to the War and lost his right leg, Bill Veeck Jr., future owner of the Indians, Browns and White Sox, had assembled backing to purchase the hapless Phillies and stock the team with Negro League all-stars. Unfortunately, the racist and cantankerous Kenesaw Mountain Landis, still the game’s commissioner, secretly arranged to have the Phillie sale vetoed and turn the team over to the National League. The End of Baseball takes this incident and creates a “what if?†scenario that is not only engaging from first word to last, but feels historically organic. We know it didn’t really happen, but damn, would we ever want it to.

In Schilling’s version, Veeck returns from Guadalcanal with his wooden leg, buys the Philadelphia Stars Negro team, then the Philadelphia Athletics from Connie Mack with the help of his minor league Milwaukee Brewers co-owner Sam Dailey, and concocts a plan to field Negro players right under Judge Landis’ nose. All the great names are in Cartwheel, Florida when Veeck and Dailey arrive at their secret spring training camp: Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Buck Leonard, Satchel Paige, a young Roy Campanella, and an aging, crazy, heroin-smacked Josh Gibson. Veeck hires catching great Mickey Cochrane to manage the team, and Mickey, hitting the bottle and mourning the death of his boy in the War, takes the job for the challenge and redemption it offers.

But no story is great without a great villain, and Judge Landis does everything he can to destroy Veeck’s dream and reputation. At first he forbids him to own both teams at once and field the Negro players at all, but when columnist Walter Winchell catches wind of the scheme and announces the A’s will have a black roster on his national radio show, the public response and President Roosevelt’s blessings turn that around in a hurry, and Shibe Park is prepared for an Opening Day like none other.

Schilling sugar-coats and mythologizes nothing, because he doesn’t need to; the story takes on the stuff of legend completely on its own. All the real-life characters are portrayed with their corresponding warts and flaws, and the ugly racism poisoning much of America at the time makes the drama three times more powerful. There are protests and riots surrounding the team, but also scores of black ball fans making the pilgrimage to Philadelphia to watch them. Veeck himself is barred from the park and watches the action through binoculars on the roof of his apartment across the street.

But there is also a treasure chest of pure baseball pleasure, and the Negro greats come alive on and off the field with a delicious vibrancy. As the evil Landis machine revs up (Monte Irvin is drafted and shipped off on the second day of the season; J. Edgar Hoover is enlisted to plant a wire on one of the coaches and root out Communists, for starters.) we begin to pull for Veeck and his team to not only take the American League pennant, but vanquish their inner and outer demons along the way. The tale’s powerful, ironic conclusion feels perfectly right and earned, and like the rest of this wonderful story, never kowtows to the sentimental drippyness that plagues so much of our baseball nostalgia.

I can’t praise this book enough. If you read only one baseball novel in your life, make it this one.

*Â *Â *

On the opposite end of the spectrum, for the reader who is comfortable with just the simple facts—and I’m talking every one

—we have an exhaustingly researched history of Negro ball in the upper Midwest. Todd Peterson’s Early Black Baseball in Minnesota

(McFarland, $29.95, to be published in October) begins in the 1870s, ends some 220 pages later in the 1920s, then follows that up with about 80 pages of appendixes and indexes, including complete game logs of the St. Paul Gophers and Minneapolis Keystones for a handful of years.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, for the reader who is comfortable with just the simple facts—and I’m talking every one

—we have an exhaustingly researched history of Negro ball in the upper Midwest. Todd Peterson’s Early Black Baseball in Minnesota

(McFarland, $29.95, to be published in October) begins in the 1870s, ends some 220 pages later in the 1920s, then follows that up with about 80 pages of appendixes and indexes, including complete game logs of the St. Paul Gophers and Minneapolis Keystones for a handful of years.

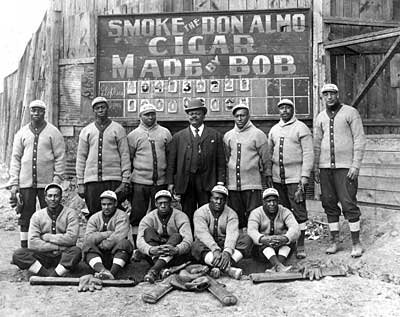

Aside from the all-star research job pulled off by Peterson, the incredible thing is that there are still hundreds of colorful characters and stories embedded in the facts. Weeding them out does take a fair amount of patience, but for the reader who can, there is a treasure trove here of great Negro ball history that’s been virtually ignored.

The book focuses on the 1907-1910 heyday of the Gophers and Keystones, two rival barnstorming black teams that steamrolled their way around the upper Midwest every summer, taking on semi-pro outfits like the Des Moines Invincibles and the Buxton Wonders, thrilling and often angering the local fans with their largely unmatched play. With such memorables as Big Bill Gatewood, Kissing Bug Rose, Noisy Wallace and Rat Johnson in the mix, who can resist these tales?

The two teams, with the Gophers being the far more professional club and the Keystones earning a reputation as a loud, more underhanded “minstrel show,†encounter the usual sickening racism of the time, nearly always in the local newspapers. (“The choicest chocolate drops in the bon-bon box†is how the Gophers are described even when being praised.) But their play is almost never affected. The 1908 Keystones went 88-19-2. The 1909 Gophers endured a 38-game road trip in 34 days through the Dakotas, Wisconsin, Michigan, and northern Minnesota—and went 30-7-1.

In between all the stats, Peterson has also wedged in some great player histories. We learn about Billy Williams (the old one), the first great Minnesota black slugger with the St. Paul Spaldings, pitcher Walter Ball, who like many of the stars, jumped from team to team.  The fortunes and fates of Gophers owner Phil Reid and Keystones magnate “Kidd†Mitchell, both black saloon owners, are also documented, along with the two teams’ natural rivalry.

Peterson may have been better served by plucking a few of the bigger characters out of this historical gumbo and giving us a more dramatic story seen through their eyes, but maybe that’s just my preference. Black Ball in Minnesota , despite its academic take, is still well worth any baseball history fan’s attention, and also includes an amazing assortment of rare photos that can stand on their own.

Jeff Polman’s fictional replay blogs of the 1924 and 1977 seasons can be accessed at http://1924andyouarethere.blogspot.com and http://funkyball.wordpress.com , respectively.

Jeff,

I’m about 75% through The End Of Baseball and I agree this is a great read.

Kevin

To correct the erroneous info in my review, “Early Black Baseball in Minnesota” is actually available for purchase right now, and at the list price of $39.95, from http://www.mcfarlandpub.com or 800-253-2187.