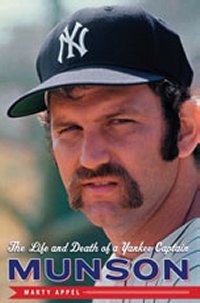

“Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain”

September 5, 2010 by Chip Greene · 1 Comment

In January 1977, shortly before resigning as Director of Public Relations for the New York Yankees, Marty Appel approached team captain Thurman Munson about collaborating on the catcher’s autobiography. Initially, Munson, who had recently been named the American League’s Most Valuable Player, was reluctant.

“I’m only twenty-nine,†Munson said. “No one does an autobiography at twenty-nine.â€

“I’m only twenty-nine,†Munson said. “No one does an autobiography at twenty-nine.â€

Appel explained to Munson that twenty-nine wasn’t especially young in the celebrity world, and that winning an MVP award “almost guaranteed that someone [Appel’s italics] would be pitching a book idea to a publisher.†What’s more, Appel continued, “if you don’t do it yourself, you’ll hate whatever is done without you- you won’t make any money, you’ll think it’s all wrong, and it will just aggravate you.”

“I’m not that interested in the money,†Munson countered. “And I’d want it to be a paperback so kids could buy it.â€

Eventually, with a little more prodding from Appel, Munson agreed to the project, yet with one reservation.

“Does it have to get personal?†Munson asked, and Appel thought, “What a strange question from a man considering an autobiography.â€

That book, Thurman Munson: An Autobiography, published in 1978 , “sold a lot more copies after [Munson} died than before,†Appel remembered thirty-one years later. “I’ve received a lot of compliments on it over the years, particularly from Munson fans.†In fact, the writer continued, “[Munson’s] wife, Diana, was especially admiring. ‘Thank you for writing it, thank god we have this,’ she said to me on the eve of his funeral.â€

In the ensuing years, Appel has written many more books. “But as I have reread that book over the years,†he explained, “I’ve always felt that Thurman held back too much, skirting over personal matters, as was his right. The publisher was pleased with the final product,†Appel continued, “so I felt I had met my obligation to give them both the book they wanted. But I was never really satisfied with it.â€

And so, to coincide with the thirtieth anniversary of Munson’s death, in 2009 Appel wrote Munson : The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain. If the 1978 book was, as Appel wrote, “a traditional baseball life story with little controversy,†this book, he explained, was “an attempt to fill in the gaps that Thurman left in telling his own story†in 1977-78.

It succeeds superbly.

What makes this version of Munson’s story so appealing is the sheer volume of people Appel interviewed to tell the catcher’s story. Whereas the original autobiography was drawn from many hours of transcribed tapes Munson had recorded, resulting in a “traditional baseball bio†that largely revealed only those aspects of his personality that Munson chose to convey, in writing the new version Appel relied on the thoughts and memories of those who were closest to Munson throughout various periods of his life. It is their candor and honesty that animates the Yankee legend and lays bare both the good and darker aspects of his seemingly complex personality.

Much of what made Munson the man he eventually became can be traced to his childhood. During his lifetime, though, and certainly in his autobiography, Munson was reticent to share details of his youth. Indeed, when Appel worked on the first book with him, “Diana,†as the writer relates in the new book, “had asked me whether [Munson] brought up much about his childhood.†When Appel explained that he had broached the subject but hadn’t gotten very far, he sensed that Munson’s wife was “just curious to know how much [her husband] had opened up.â€

Munson’s aversion to talking about his childhood is certainly understandable. The youngest of four children, he grew up in Canton, Ohio, the town which he never left and which is today his final resting place, in a very difficult family atmosphere. His father, Darrell, the single most villainous character in the book, was a truck driver and a very intimidating, angry man. Sports became for Thurman an escape from a hostile home life. In relating these years, Appel tracked down two of Munson’s siblings, Darla, the eldest child, and also Thurman’s brother, Duane, and the two maintain a presence throughout the book. Their memories of this formative period of Thurman’s life and their insight into their brother’s relationship with his parents provides a glimpse into the dynamics that drove Munson not just to excel in athletics but also to later pull away from his own family in favor of Diana’s. (Their father would come home after a week away, Darla volunteered, and “just start hitting us. A fist across the head. Scary. He’d throw things too, if that was convenient. And I remember Mom off to the side crying and saying, Stop! Enough!) Beyond contributing her memories of those years, Darla also provided Appel with a guided tour to all the homes, schools and landmarks in Canton that were integral to Munson’s youth.

Perhaps none of those sites was as important as Lehman high School. It was there, as captain of the football, basketball and baseball teams, that Munson became, states Appel, “one of the greatest athletes the school had ever known.†In all, he earned nine varsity letters, as well as all-city and all-state recognition in each sport. When, despite receiving letters of interest from over 80 football programs, Kent State became the only school to offer Munson a full scholarship to play baseball, his decision about where to play became easy, and he went on to achieve legendary status at the school (the only player in school history to have his number retired), earning first-team All-American honors following his junior year in 1968. In June of that year the New York Yankees selected him with the fourth pick of the amateur draft, and by the following year, after just 99 minor league games, Munson was in the major leagues to stay.

Those pre-Yankees years are vividly brought to life by many who played and coached with and against Munson at every level of competition, and are often done so with wildly visual anecdotes- like the time Munson and some of his Cape Cod League teammates were driving in a convertible to a road game and he threw a ball over an underpass from about 100 yards away, only to catch it on the other side after the car sped up. In his sources Appel lists almost 30 people, some famous, some not, whose recollections portray not only Munson’s abundant physical skills, but also the athlete’s tremendous confidence and will-to-win. From Lehman teammates like the flame-throwing Jerome Pruett, whose fastball only Munson could handle, to future major leaguers Steve Stone, Munson’s Kent State roommate and battery mate, and Bobby Valentine, his Cape Cod League teammate, ÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂÂeach person’s contribution is helpful to the reader in understanding the uniqueness of Munson’s talent.

His life with Diana, of course, permeates Munson’s story. “Thurman would always call her Diane,†Appel writes, “almost as though he hadn’t heard the name right or just wanted to save a syllable.†Munson and Diana Dominick met at school when he was twelve, and from then until the end of his life, they were inseparable. Although Appel did not interview Diana for this book, they have corresponded, he explains, for almost forty years, and her singular contributions illuminate Munson the father as no one else could. (Diana loved when Thurman was home, offers Appel, because four-year old Michael would finally sleep through the night; and “when the girls needed their hair brushed, they wanted their Daddy to do it… Daddy does it so gently.â€) It was a side of his personality Munson rarely let the public see.

About Munson’s years in the Bronx Zoo, including his often-stormy relationship with the press, Appel covers little new ground. It’s not his fault; over the past thirty years, that era has been well-chronicled in other books, and seemingly every story that can be told has been (although the fact that Munson stubbornly insisted that George Steinbrenner remove the clause in his contract forbidding flying is eerily ironic). Still, Appel offers a unique perspective. Given that the author joined the Yankees’ front office in 1968 (the year Munson was drafted) and left early in ’77, and that he had unique access to events that took place in the clubhouse, in Steinbrenner’s office and on team flights, Appel observed first-hand most of the interactions Munson had with his teammates and reporters. Many of the scenes, Appel explains in his sources, are re-created from memory, although he also conducted twenty-two new interviews with Munson’s teammates, including Chris Chambliss, Ed Figueroa, Ron Guidry and Reggie Jackson, as well as fifty-seven baseball officials and media personalities.

Also, while Appel effectively depicts Munson’s ‘grumpy’ side by detailing the catcher’s infamous battles with the press , it was refreshing to learn that he could also be gracious at times: “When I was a rookie reporter in spring training, he saw me waiting forlornly at the ballpark for a taxi,†said Marty Noble, then of the Bergen Record . “So he offered me a ride to my hotel, which was out of his way. He didn’t make a big deal of it. It didn’t matter that I was a writer. He had an inherently good side.†Munson also once offered to pay to bring Daily News writer Phil Pepe’s family to spring training.

Finally, there’s the accident- August 2, 1979. As the book progresses, Appel masterfully builds to the plane crash by detailing how Munson had become increasingly torn between continuing his career in New York and the desire for the life he had built in Canton, including his burgeoning real estate ventures; in order to get home as fast as possible Munson took up flying, and his growing obsession with aviation led to the purchase and piloting of bigger and more powerful aircraft. Compiled from a multitude of contemporary sources, including the National Transportation and Safety Board’s accident report and a verbatim transcript of a 2004 ESPN interview given by Munson friend and business associate Jerry Anderson, who survived the crash, the last third of the 355-page book is a meticulous description of both the aircraft (a Cessna Citation) and the fateful decisions Munson made that day. The account is vivid and stark, and it left me feeling the same sad way I did when I was seventeen years old and heard about the untimely death of one of my favorite players. Appel then finishes the historical perspective by faithfully recounting Munson’s funeral and the public’s outpouring of affection, and he concludes by bringing us up to date on Diana and the rest of Munson’s family.

For anyone who is a baseball fan or a fan of good biography, I recommend you read Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain. It reminds us all of just what a legend we lost.

When not reading and writing about baseball, Chip is a management consultant. A lifelong resident of the Washington, DC, metro area, in the summer of 2008 he moved to Waynesboro, Pennsylvania, still close enough to retain his lifelong enthusiasm for the Baltimore Orioles. Chip is a member of SABR and writes for the BioProject website, as well as contributing to several upcoming SABR book projects. He also writes for Yankees Annual magazine. Chip’s interest in baseball history is fed by a continuous fascination with the career of his grandfather, Nelson Greene, who briefly pitched for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Comments

One Response to ““Munson: The Life and Death of a Yankee Captain””Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying about this post...[…] and a long-distance trucker, had a notorious temper. The eldest of the four children, Darla, told Munson’s biographer Marty Appel that Darrell would come home after a week away and […]