Bob Stephens: Minor League Pitcher and WWII Fighter Ace

June 11, 2011 by Gary Bedingfield · 1 Comment

Bob Stephens’ baseball career was interrupted by military service after just one season, but he wasn’t about to let that stop him from reaching for the sky. As a P-51 Mustang pilot, Stephens shot down 13 enemy fighters, attained the rank of lieutenant-colonel before his 24th birthday and served with the Air Force for 18 years. However, the seemingly unstoppable Missourian’s life was tragically cut short on what should have been a routine flight in April 1960.

Robert W. Stephens was born on September 16, 1921 in St. Louis, Missouri. The son of John (a Switch Master with the Missouri Pacific Railroad) and Bertilla Stephens, he grew up on Pernod Avenue in south St. Louis in a small, one-bedroom apartment which meant young Bob had to sleep on the couch. He attended Roosevelt High School where he lettered in baseball and football, and also ran track at Roosevelt. A pitcher and shortstop, he was playing sandlot ball after school and despite hailing from a city that boasted two major league teams at the time, he was signed by the Boston Braves in June 1941 to a contract with the Evansville Bees of the Three-I League.

Evansville promptly assigned the young right-hander to the Bowling Green Barons of the Class D Kitty League (the nickname given to the K-I-T League, which was short for the Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee League). Bowling Green is in south central Kentucky, about 300 miles southeast of St. Louis, and professional baseball had come to the town in 1939 when Vick Smith, Sr. – a local businessman – bought the Lexington (TN) Bees franchise.

At a time when Bowling Green was an isolated community due to poor highway connections, ballgames and the movies were the biggest things in town. The Barons could always expect a good crowd at the Fairgrounds Stadium in Lampkin Park and they didn’t disappoint the fans by finishing second in 1939 and winning the Kitty League pennant in 1940

When Stephens joined the Barons in June 1941, 40-year-old Ossie Bluege – who had an 18-year major league career as an infielder with the Washington Senators – was the manager and Ossie’s brother, Otto, an infielder with the Reds in the early 1930s, was playing his last season of pro ball as the Barons’ shortstop. The 1941 Barons, with only two players returning from the previous year’s pennant-winning squad, had gotten off to a slow start and were sitting in the league basement. Having dropped 11 of their last 12 games, Ossie was fired as manager in late June, and another former big leaguer, 40-year-old outfielder Mel Simons – who played with the White Sox in the early 1930s – took over as skipper of the club.

Stephens had a steady rookie season with the seventh-placed Barons. He made his first appearance as a relief pitcher against the Fulton (KY) Tigers on June 13 in a 9-1 loss. His first start came on June 26 against the Jackson (TN) Generals and it was an impressive showing; going the distance he shutout the Generals after the first inning allowing eight hits in a 6-3 win. He was the starting pitcher again on July 5 in a 5-4 win over the Union City (TN) Greyhounds and followed that up on July 15 as the starter in a 7-2 win against the Paducah (KY) Indians. The following night – the same night future Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio hit in his record-setting 56th and final consecutive game – Stephens helped the Barons beat Paducah, 6-2, with a relief appearance. During August he helped beat the Owensboro (KY) Oilers and Paducah, while making relief appearances in losses to Jackson, the Mayfield (KY) Browns and the Hopkinsville (KY) Hoppers. He beat Mayfield, 5-4, on September 1 and his final appearance of the season came on September 4 as a reliever in a 13-inning, 10-9, loss to Hopkinsville.

In 23 appearances on the mound he was 5-6 with 43 strikeouts in 127 innings, and his earned run average was a respectable 3.97 (second best on the team).

It looked like the young Missourian had a promising career ahead of him but 1941 was to be his only season in professional baseball. On December 7, 1941, peace in the United States came to an abrupt end as the Japanese launched a devastating surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that sank or damaged 18 warships of the United States Pacific Fleet and claimed over 2,000 lives. Initial word of the attack was broadcast on radios across the mainland about an hour and a half after it began. Unlike previous wars, in which much greater time passed before dispatches from distant battlefields reached home, Americans knew they were at war while the bombs were still falling. The day of instant journalism had arrived and Pearl Harbor, at the time a place few Americans could point to on a map, instantly and lastingly became a household name.

Pearl Harbor sent the nation into a wave of overwhelming patriotism. There was an immediate rush to enlist and Bob Stephens entered military service with the Army Air Corps on February 19, 1942 (the Barons disbanded with the collapse of the Kitty League in June of the same year as the war took its toll on available manpower).

Just 20 years old, Stephens began training as a pilot in March 1942. Primary flight training in a Stearman PT-13B Kaydet biplane commenced on March 31 at Cal-Aero Academy, an independent flying school based at Ontario, California. After completing 60 flying hours he advanced to Basic instruction in June 1942 in the Vultee BT-15 Valiant, including cross-country, instrument and formation flying. Having completed 70 hours flying time he then transferred to Luke Field, near Glendale, Arizona at the end of July 1942 for Advanced instruction. Flying the North American AT-6A Texan, Aviation Cadet Stephens training included flights to Prescott, Yuma, Blythe and Tucson.

On September 29, 1942, about the same time he would have been winding up his second season in professional baseball, Bob Stephens earned his wings and an Army Air Force commission at Luke Field.

Eager to get his hands on a real fighter plane, Stephens began transition training on the Bell P-39D Airacobra in October. One of the principal American fighter airplanes in service at the start of the war, the Airacobra was the first fighter in history with a tricycle undercarriage and the first to have the engine installed in the center fuselage, behind the pilot.

In January 1943, Stephens joined the newly formed 355th Fighter Squadron – with its distinctive “Pugnacious Pup†insignia – at the Tonopah Bombing and Gunnery Range in Nevada. The 355th were assigned to Hayward Army Air Field on the eastern shore of the San Francisco Bay in the following months for further intensive training before relocating to Portland Army Air Base, Oregon, in May 1943, as part of the Northwest defensive setup and on alert for possible attack by the Japanese.

During this time, fate played a very unusual part in bringing Bob Stephens together with local girl, Adele Steinbart. Adele and her best friend, Mary, were working in downtown Portland. Mary was dating a guy who was transferred to a military base in Florida. So, for Easter she sent him a live rabbit. The gentleman in question promptly responded by sending Mary a live three-foot alligator in a long box. When Mary received the alligator she didn’t know what to do with it so she called Adele for help. Adele suggested the alligator could be given to Mary’s sister, who was married with two children, and happened to live about two blocks from the main gate at Portland Army Air Base. When they arrived, the sister refused to have the alligator in the house, so Adele and Mary walked over to the base and called the Officers Club to see if there might be any takers. Adele made the phone call and it was Bob Stephens who answered. He and another officer came out to the gate to meet the girls and the alligator. The two officers had a friend with the nickname “Alhambra Alligator†and they thought it would be great fun to put the alligator in his bed. They took the animal from Adele and Mary, and told them that they would be back at the gate in about 20 minutes. When the officers returned, Adele asked them if they wanted to come over to her parents’ house for some roast beef sandwiches. Over the next few weeks, Adele and Bob began seeing each other and a romance soon blossomed.

During the summer of 1943, the pilots of the 355th had no idea if they and their P-39s were destined to be fighting against the Japanese in the Pacific or the Germans in Europe and North Africa. In October 1943, the squadron departed from Portland by train and made its way across the United States to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. They were headed for Europe and on October 20, the squadron departed aboard the liner Athlone Castle as part of a large convoy bound for Great Britain. Two weeks later, the Athlone Castle docked at Liverpool in northwest England.

Home for the 355th Fighter Squadron, as part of the 354th Fighter Group, Ninth Air Force, was to be Boxted Airfield (USAAF Station AAF-150), approximately four miles northeast of Colchester, Essex, in eastern England. The airfield had been vacated by the 386th Bomb Group in September and had a main runway 6,000 feet long and two intersecting runways that were 4,200 feet each in length.

Great excitement surrounded the squadron when they learned they would be flying the new Mustang fighter planes. The North American P-51B Mustang was capable of 430 mph at 25,000 feet. Armed with four .50 caliber machine guns mounted in the wings and with a reliable engine and a huge fuel load, it could accompany Eighth Air Force B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators all the way to Germany and back.

Stephens began transition training on the P-51 on November 9, 1943, and on December 1, he made his first fighter sweep across the English Channel to German-occupied Holland. On December 5, Stephens performed his first bomber escort, accompanying Allied bombers to Paris, France. Over the next few days he escorted bombers to Kiel and Bremen in Germany.

On December 20, Stephens encountered enemy fighters while escorting bombers to Bremen and damaged a Messerschmitt Me 109. On December 31, he shot down his first Me 109 while escorting B-24 Liberators to Bordeaux, France. Upon returning to Boxted, First Lieutenant Stephens had to file an “Encounter Report†to claim the destroyed airplane. “Our squadron, in which I was blue flight leader, was flying at an altitude of 25,000 feet approximately 5,000 feet above the bombers,†his report stated that day. “I noticed a straggler (B-24) being attacked by three (3) Me 109’s. I reported this to my squadron leader and went to the assistance of the straggler. As we dove the bomber was hit and started to spin down, the E/A began to circle the bomber and I picked out my target, joined the circle, closed to about two hundred (200) feet and gave him a three (3) second burst. He went to pieces and I saw smoke coming out of the cockpit, another two (2) second burst and he exploded. He took no evasive action.â€

Stephens destroyed another Me 109 on January 11, 1944, and claimed a further five enemy planes during February, including a Messerschmitt Me 110 twin-engine heavy fighter on February 21 and a twin-engine Messerschmitt Me 410 while escorting bombers on February 22. “I saw a straggler being attacked by three Me 410s,†he reported upon his return to base. “Picking out one of the ‘410s as my target, I worked in behind him. He saw me and started a steep spiral down. Following him, I gave him a few short bursts. Observing no strikes, I pulled off him at 12,000 feet. I circled around once more and saw that the same ‘410 was climbing back up towards the box of bombers. I waited for him and got behind him, this time unnoticed. With only one gun firing, I shot several long bursts before I saw strikes on his left engine nacelle. Then the engine blew up and the plane caught fire. I closed in, still firing, and observed more strikes all over the fuselage. Pulling up so as to avoid running into him, I rolled left to see the entire ‘410 engulfed in flames.â€

At around this time, he also experienced one of his most life-threatening encounters of the war. After a long engagement with enemy fighters, Stephens’ Mustang had run out of ammunition and a German fighter came after him. “I was watching the Hun’s eyes as we flew side by side and slowly drew near to him until we were wingtip to wingtip,†he told a Stars and Stripes reporter. “Then he pulled up trying to make me get ahead and in line with his guns. I throttled back and then we both peeled off. I had driven him off and then one of my squadron got him.†Records show the German fighter was an Me 110 and it was First Lieutenant Lowell K. Brueland who came to the rescue and shot him down.

On April 1, 1944, Captain Stephens was appointed commander of the 355th Fighter Squadron. He destroyed a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter plane on April 9 and claimed another on April 29 while on a five-hour bomber escort to Berlin.

The 354th Fighter Group left the relative comfort of Boxted and moved further south at the end of the month to provide tactical air support to the imminent invasion of France. Living in tents and flying from the steel matting runway of Lashenden Advanced Landing Ground, near Headcorn, Kent, Captain Stephens claimed his third Fw 190 on May 9. On June 4 he led the squadron on a dive-bombing mission against a railroad junction at Bourges, France. As the Mustangs came off the target they spotted an unusual sight. A Focke-Wulf Fw 56 trainer was performing aerobatics in their full view. Stephens gave the trainer a short burst with his guns which promptly took its landing gear off, and then two other Mustangs attacked the little plane and turned it into a fireball.

The 354th Fighter Group left the relative comfort of Boxted and moved further south at the end of the month to provide tactical air support to the imminent invasion of France. Living in tents and flying from the steel matting runway of Lashenden Advanced Landing Ground, near Headcorn, Kent, Captain Stephens claimed his third Fw 190 on May 9. On June 4 he led the squadron on a dive-bombing mission against a railroad junction at Bourges, France. As the Mustangs came off the target they spotted an unusual sight. A Focke-Wulf Fw 56 trainer was performing aerobatics in their full view. Stephens gave the trainer a short burst with his guns which promptly took its landing gear off, and then two other Mustangs attacked the little plane and turned it into a fireball.

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, Stephens was escorting C-47s and their gliders to the Utah Beach area and continued providing support as the Allied forces moved inland over the coming months. On June 14, he got his first flight in the new P-51D Mustang, which, with its distinctive bubble-top canopy, became one of the most iconic fighter planes of the war.

By mid-June, the 355th Fighter Squadron was operating from an airfield known simply as A-2, near Cricqueville in Normandy. Stephens destroyed another Fw 190 on June 17, flying his faithful P-51B, appropriately nicknamed “Killerâ€, and claimed another for his 10th kill on July 17 during a fighter sweep near Paris.

“My dad really liked to box,†explains his son, Jeff Stephens, “and he participated in this sport, as an amateur while growing up. He lost very few of his boxing matches and usually won by TKOs. The nick-name “Killer†was given to him by a friend of his fathers for his success in the ring. When the time came to name his airplane, my grandfather suggested he name is plane “Killerâ€, which my father did. After the war, his passion for boxing continued, as he usually had body bags and speed bags hanging up in the garage.â€

On July 27, the squadron fully converted to the P-51D and moved to Gael Aerodrome, a former Luftwaffe base in Brittany, in mid-August 1944.

On August 9, Stephens was promoted from captain to major. He celebrated on August 25 by claiming his first kills in a P-51D with two Fw 190s destroyed. On that day, the 355th Fighter Squadron earned a theater record for in-the-air kills for one squadron in a day with 25 enemy planes shot down.

August 28 was to be Stephens’ last sortie in Europe after nine months in the combat zone. In his typical style, he destroyed yet another Me 109 bringing his confirmed total to an incredible 13 kills and claiming his position as leading ace of the 355th Fighter Squadron. During his time in Europe, Major Stephens had flown over 233 hours during122 missions.

Stephens returned home to the United States in September 1944. He enjoyed 20 days leave with his family in St. Louis and sent a telegram to Adele in Portland asking her to come to St. Louis to get married. Since leaving Portland for England almost a year earlier, the couple had regularly written to each other. A few days later, Adele and her mother arrived in St. Louis and they were married on October 24.

Still only 23 years old, Stephens attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in 1945 and was appointed chief of operations of the 1st Tactical Air Division at Esler Field in Alexandria, Louisiana. The 1st Tactical gave air support to ground units in training and participated in air-ground maneuvers up until the surrender of Germany and Japan.

Stephens had been out of baseball for four years by the end of 1945. As an airman, he had climbed through the ranks at an astonishing rate and chose the military as a post-war career. “Bob has made a great soldier and flyer,†his mother told The Sporting News on June 7, 1945, “but if it hadn’t been for the war, we think he also would have made a fine ball player.â€

Stephens went on to serve with the occupation forces in Germany, and in Italy and Turkey; was promoted to Colonel in 1955; commanded the 12th Flying Training Wing at Bergstrom Air Force Base, Texas, in 1956; the 413th Tactical Fighter Wing at George Air Force Base in California in 1958 and the 31st Fighter Wing, also at George AFB, in 1959. By 1960, he was a father of three children and Director of Inspection for Tactical Air Command, based at TAC Headquarters, Langley Air Force Base, Virginia.

On April 6, 1960, 38-year-old Colonel Stephens was holding an Operational Readiness Inspection on the 474th Tactical Fighter Wing at Cannon Air Force Base in Clovis, New Mexico.

At around 12.15pm, he was seated in a North American F-100F Super Sabre two-seater fighter on the runway at Cannon AFB. “My dad was in the back seat and Lieutenant L.W. Emerson was the pilot,†explains Jeff Stephens. “My dad was doing “a check ride” for the young lieutenant as part of his inspection of the Fighter Base.â€

First Lieutenant Lloyd Warren Emerson, a 27-year-old pilot with the 429th Tactical Fighter Squadron, made lift-off as normal but at an altitude of about 300 feet and a speed of 190 miles per hour, the afterburner failed. In an effort to avoid a crash Emerson dropped the heavily loaded external fuel tanks which lightened the jet fighter enough that it stayed in the air. His remaining power, however, was not enough to keep the plane flying. With a group of buildings in his path, Emerson made a sharp left turn causing his wingtip to hit a railroad boxcar, flipping the airplane over and imminent impact with the ground, instantly killing himself and Colonel Stephens.

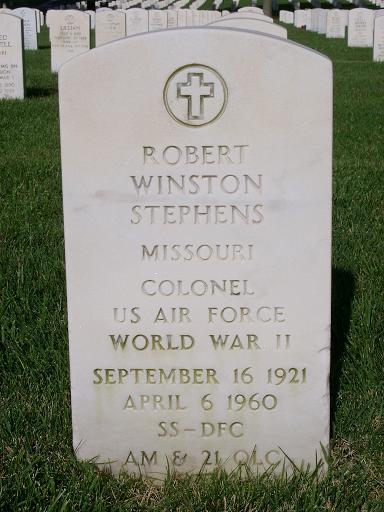

During 18 years of service, Colonel Stephens had flown more than 3,300 hours and had been awarded the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with 21 Oak Leaf Clusters, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with four Bronze Service Stars, World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal with Germany Clasp, National Defense Service Medal, Distinguished Unit Citation Emblem with one Oak Leaf Cluster and Air Force Longevity Service Award Ribbon with three Oak Leaf Clusters. In addition, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star by the French Government.

During the summer of 1961, Robert Stephens’ father asked his nephew, Lester Lurk and his wife Leanna, if they might name their soon-to-be-born child after his late son. “Uncle Jack hesitantly asked us, if we had a boy, would we name him after Robert,†recalls Lester. “We immediately responded with a ‘yes’ as we were flattered with the request. Although we really never knew him personally, we were so proud to use the name because of the courageous life he lived.”

Colonel Robert W. Stephens is buried at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

A few words from his son, Jeff Stephens:“For those of you who grew up in a military family, you know first-hand what it was like not having a parent home on a regular basis, relocating every 12 to 18 months, and not knowing when, or if, your father would return home. Making the United States military a career is a “calling†which not all Americans are capable of because of the required sacrifices. I hope that each of you who read this bio, along with other military bios, will stand up with me and salute those serving and pray for those who have fallen. My Dad was a great guy, as I am sure your father was also. Over the years we have missed him terribly.

“I can speak for the entire family in thanking that Gary for providing us with information we never knew about my Dad, once he left home after high school and started playing minor league baseball. For Gary’s efforts we sincerely thank him for his research in putting this biographical information together.”

Sources of information:

354th Fighter Group by William N. Hess, Osprey Publishing (Oxford, 2002)

Pugnacious Pups: 355th Fighter Squadron Log by 1/Lt. Donald F. Snow

Stars and Stripes newspaper 1944/1945

Clovis News Journal (1960)

The Sporting News (1944/1945)

Kentucky New Era (1941)

Park City Daily News (2004)

Robert W. Stephens log book (March 31, 1942 to September 5, 1944)

http://www.354thpmfg.com – 354th Pioneer Mustang Fighter Group

http://354thfightergroup.homestead.com – Pioneer Mustang Group

Family members of Robert W. Stephens

Thank you to Jeff Stephens for his time, generosity and support in helping to compile this biography about his father. If you served with Robert Stephens, or a family member did, his son, Jeff, would be very pleased to hear from you. You can send an email to me at gary@baseballinwartime.com and I will glady pass it along to Jeff.

You can view a full gallery of photos and gun camera footage relating to Bob Stephens at BaseballinWartime.com

http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/stephens_robert.htm

Comments

One Response to “Bob Stephens: Minor League Pitcher and WWII Fighter Ace”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying about this post...[…] Bob Stephens: Minor League Pitcher and WWII Fighter Ace … World War II Victory Medal, Army of Occupation Medal with Germany Clasp, National Defense Service Medal, Distinguished Unit Citation Emblem with one Oak Leaf Cluster and Air Force Longevity Service Award Ribbon with […]