My Proudest Moment at the Hall of Fame

June 26, 2011 by Gabriel Schechter · 3 Comments

Maybe it’s fitting that my proudest moment at the Hall of Fame did not occur at the museum or even in my office in the library, but outdoors at the Clark Sports Center. Though I enjoyed every day I spent at the library (except for the last one), we’re coming up on the fifth anniversary of the one moment which, for me, crystallized the Hall of Fame’s threefold mission to “preserve history, honor excellence, and connect generations.” That all happened on July 30, 2006, at the annual induction ceremony.

That was the year when the Hall of Fame went back in time and inducted 17 significant figures from the old Negro Leagues. There was a lot of controversy not because of the 17 electees but because of one person who was not elected: Buck O’Neil. The hugely popular O’Neil, already in his 90s, was on the committee that voted in 17 of the 39 candidates, but he reportedly fell one or two votes short himself. One rumor that circulated around the Hall was that he urged that he not be elected in lieu of other candidates.

Just as history had given short shrift to so many long-forgotten Negro Leagues standouts, so the 2006 induction ceremony short-changed them. All 17 were inducted in a mere 36 minutes, less time than it took Carlton Fisk to deliver his acceptance speech in 2000. Some of the inductees had relatives present, and they were instructed simply to read the text on the plaques. A few of them sneaked in a few extra comments, including descendants of Effa Manley and Jud Wilson. For the rest, induction consisted of the plaque being read by Bud Selig, along with general remarks by O’Neil and Jackie Robinson’s daughter Sharon. The Hall had made a sincere effort to find as many relatives as they could, but with most of the inductees long since deceased, that was a tough task. Still, for the limited number of relatives in attendance, five or ten minutes at the microphone wouldn’t have been too much to grant.

Let’s talk about the plaques, which are the enduring memorial to those 17 now-immortals. Traditionally, the plaque text has been written by the Hall’s head of public relations. For a couple of decades, from the 1970s to the mid-90s, that meant William Guilfoile. Following him, the solemn task was performed by Jeff Idelson. Since Idelson became the Hall’s President in 2008, his PR successor, Brad Horn, has written the plaque text.

The exception to this practice was 2006, when Idelson understandably felt that the workload of composing 18 plaques (the 17 Negro Leaguers plus BBWAA electee Bruce Sutter) was too much. Instead, the assignment was delegated to three members of the library’s research staff: Tim Wiles, Bill Francis, and me. We actually held a draft to decide who would write which plaques; Bill and I chose six apiece, and Tim did five. I don’t remember the order of my first five picks, but they were Sol White, J.L. Wilkinson, Biz Mackey, Cum Posey, and Jud Wilson. My last pick was a guy I knew nothing about, Andy Cooper. Little did I know that just a few months later, his plaque would result in my proudest Hall of Fame moment.

The three of us went off and wrote the first drafts of the plaques. There followed a group meeting with librarian Jim Gates and Jeff Idelson, at which we critiqued the drafts, decided what needed to be omitted and what needed to be emphasized, after which we were sent back to put together final versions which Idelson would tweak into permanent wordings. I think Tim and Bill would agree with me that what you see on those 17 plaques is approximately 75% of what we originally wrote.

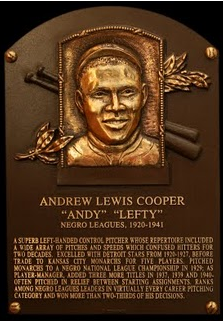

We had the library’s wealth of research material to draw from, and the executives were the easiest to write. I knew a fair amount about Biz Mackey, and Jud Wilson’s accomplishments were easy to track down. But Andy Cooper was fairly elusive. When the Negro Leaguers were elected, the Hall of Fame had issued statistical summaries of their careers, largely compiled by historian Dick Clark, and the numbers were useful though they never tell the whole story. There were a few items in Cooper’s clippings file in the library which helped, and I found some tidbits in John Holway’s oral histories of Negro Leaguers. Here is what I finally submitted to Jeff Idelson:

TALL PITCHER UTILIZED WIDE ARRAY OF PITCHES, SHARP CONTROL, AND CHANGES OF SPEED TO WIN CONSISTENTLY FOR TWO DECADES. EXCELLED WITH DETROIT STARS FROM 1920-1927, THEN TRADED TO KANSAS CITY MONARCHS FOR FIVE PLAYERS. LED MONARCHS TO NEGRO NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP IN 1929 AND LATER MANAGED THEM TO THREE MORE TITLES. RELIEF ACE BETWEEN STARTING ASSIGNMENTS, REGARDED AS SECOND ONLY TO BILL FOSTER AMONG NEGRO LEAGUES LEFT-HANDERS.

Here is the improved version on Cooper’s plaque:

On July 30, my induction ceremony assignment was along the chute through which invited guests entered the field next to the gym where the ceremony has been held since the mid-1990s. Looking from the stage, I was on the left, about even with the front of the stage, so I didn’t have a very good view of the people who were up there or the inductees’ representatives, but I could hear the plaques being read and the brief remarks. Near my post sat a large group of Jud Wilson’s relatives, and I talked to a few of them during the ceremony. They were thrilled to be there, especially when their designated speaker, Sha’Ron Taylor, accepted Wilson’s plaque. She cleared up a big mystery in my mind. I had always read that Wilson’s nickname, “Boojum,” represented the sound his booming line drives made when they bounced off outfield walls. I couldn’t make the connection–until Taylor pronounced the word, which she did with gusto two or three times during her brief remarks. The nickname, it turned out, was “buh-ZHOOOM!!” Now I can hear it loud and clear.

On July 30, my induction ceremony assignment was along the chute through which invited guests entered the field next to the gym where the ceremony has been held since the mid-1990s. Looking from the stage, I was on the left, about even with the front of the stage, so I didn’t have a very good view of the people who were up there or the inductees’ representatives, but I could hear the plaques being read and the brief remarks. Near my post sat a large group of Jud Wilson’s relatives, and I talked to a few of them during the ceremony. They were thrilled to be there, especially when their designated speaker, Sha’Ron Taylor, accepted Wilson’s plaque. She cleared up a big mystery in my mind. I had always read that Wilson’s nickname, “Boojum,” represented the sound his booming line drives made when they bounced off outfield walls. I couldn’t make the connection–until Taylor pronounced the word, which she did with gusto two or three times during her brief remarks. The nickname, it turned out, was “buh-ZHOOOM!!” Now I can hear it loud and clear.

But the joy of hearing “buh-ZHOOOM!!” paled next to the spine-tingling moment when Andy Cooper Jr.–one of ten Cooper relatives on hand–read his father’s plaque. He was a little boy when his father died of heart disease at the age of 43 in 1941, and didn’t remember anything of his father’s baseball exploits. What he knew was on that plaque. I think he’s a minister; if not, he should’ve been, because he read the plaque with evangelical zeal. As Detroit Free Press writer John Lowe wrote following the ceremony, “Cooper’s son regularly raised his voice when he read his father’s plaque. He emphasized the words ‘in relief’ during this line: ‘Often pitched in relief between starting assignments.'”

You bet he raised his voice. For him, the words on that plaque represented a revelation to the world of his father’s greatness, and his reading of them a once-in-a-lifetime chance to call out to his father and let him know he will live forever in the plaque gallery at the Hall of Fame. Nobody who spoke that day reveled more than Andy Cooper Jr. in the words engraved on a plaque. And I wrote those words. Standing there and listening to how my words had moved this man so powerfully gave me goosebumps, and I’ve gotten them again while writing this.

Talk about preserving history, honoring excellence, and connecting generations! I never got to meet Andy Cooper Jr. and might never cross his path again, but we are linked by words I typed dispassionately on a computer and which he so stirringly delivered to the world. His resounding pride made that my proudest moment as a representative of the Hall of Fame.

Wonderful inside stuff here, Gabriel. I’d never heard of Andy Cooper, so a double dose of gratitude to you for enlightening us about his baseball exploits and for sharing the secrets behind the ceremony at which his son read the words aloud that you crafted with such care and devotion in tribute to his father. Your recounting of that moment gave ME goosebumps!

Gabe,

I enjoyed your article very much. I was at the 2006 induction and I agree that time should have been alloted for the few living relatives to speak like the ones who did say something.

I hope you get the opportunity to reach Andy Cooper’s son and express your feelings to him like you so eloquently did in this article.

Wonderful piece, Gabriel. Thanks for sharing.