A Glimpse of Eddie Mathews in 1989

November 18, 2012 by Arne Christensen · 8 Comments

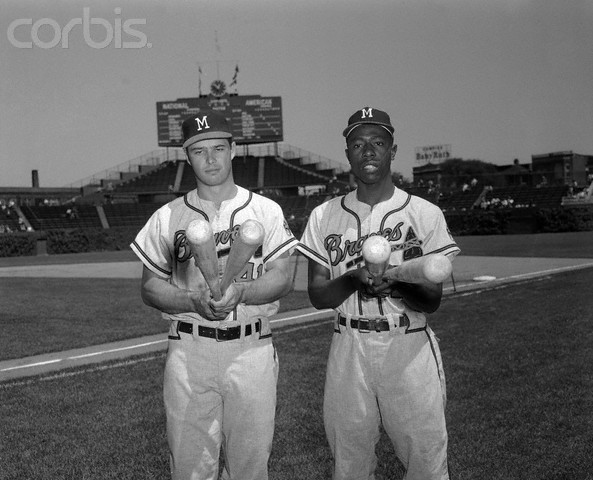

In a 1991 book called Stolen Season , journalist David Lamb describes his solo journey by RV through the U.S. on a tour of the minor leagues in 1989. Lamb, a devoted fan of the Milwaukee Braves in the late ’50s as a boy in Boston, which the Braves had left a few years earlier, caught up with Eddie Mathews in Durham, North Carolina. Mathews was teaching hitting to the Braves’ AA team there in his role as minor league hitting instructor. Eddie died from complications of pneumonia at age 69 in February of 2001. His life in and out of baseball had some clear parallels with Mickey Mantle , and I’m sure a few people would argue that he was at least Mantle’s equal as a player. But that’s not a point to be contested here.

Eddie was born on October 13, 1931, exactly a week before Mantle, in Texarkana, Texas. Texarkana is right on the Arkansas border, about 150 miles due south of Commerce, Oklahoma, where Mantle grew up and became a multi-sport star in high school. Eddie, though, moved on to Santa Barbara, California, at age six. From that point onward, David Lamb is the source for the bulk of this story.

About fifty years after that move, Mathews was sitting alone at the end of the Durham Braves’ dugout, head cupped in his hands, sweating profusely and chain-smoking. He had a thundering hangover. He was nearly sixty in the summer of ’89, balding, with a bad back, and every day was a sort of unexpected bonus—one denied his father, who had died of tuberculosis during 1953, Mathew’s second year in the major leagues. (Mantle’s father also died in his son’s second year with the Yankees, in 1952.)

As of that 1989 summer, Mathews had had his nose broken four times, twice by baseballs and twice in barroom fights. It was normal in the ’50s for players to drink and hang around the bars for several hours; Mathews did that, and he both reaped the benefits and suffered the consequences. Hank Aaron told him, “You gotta slow down, Eddie.” Mathews retorted: “And have no fun? Shit, no!”

There was segregation in those days too, and Mathews, looking back on how Aaron was refused admittance to the dining cars of trains for that reason, said: “It makes me angry that I didn’t stand up and be counted and say, ‘What’s this shit?’ I was a chicken shit not to have said anything, but we didn’t even think about it then.”

Mathews used the knowledge gained from his days as a player to patiently school the Braves’ teams in Greenville, S.C., Durham, and Richmond on the art of hitting, traveling the circuit between those teams throughout the season, usually with his fourth wife, Judy. Eddie: “Having her along keeps me out of the bars.”

He was a shy and private man despite the brawling and drinking with teammates: Mathews hated having to go up before the groups of minor leaguers in spring training and talk about baseball and hitting. Away from that spotlight, he was a very good teacher who didn’t turn aside the “no prospects,” as the executives down in Atlanta called players who weren’t heading up to the big leagues. About that, he said: “You see a kid who’s twenty-five and still in Durham, and you just wonder if he realizes he isn’t going to go very far. But you can’t just walk away from him.”

The minor leaguers rarely knew if he had hit left-handed or right-handed, what position he’d played or when. One player told Lamb: “What do you mean he played for the Milwaukee Braves? There’s no Milwaukee Braves.” Talking about one player in Richmond who turned out pretty well with the Braves, Mathews said: “I talk to Dave Justice and he just gives me a big grin and keeps making the same mistakes. He doesn’t hear me, like he’s sealed up inside.”

He added: “I’ve been here three years and I get shocked when they say ‘What position did you play?’ If they don’t know who I am, what stats I put on the board, then why are they going to relate to what I tell them? It’s so totally frustrating because I’m sure I’ve never hurt anybody, and I think I’ve helped a few.”

Assessing his character, Mathews said: “I know I’m a ding dong, but in my day, if you hit .330, it was OK to be a ding dong.” One day at a rooftop hotel bar in St. Louis, he and teammate Bob Buhl were drinking, listening to four of the locals say “the Braves suck” over and over again at a nearby table. The two Braves started up as though to walk out, came up behind the four patrons, “and beat them zingy,” as Eddie said. That and the other brawls notwithstanding, he had an honorary deputy sheriff’s badge for DeKalb County, Georgia, which was a gift from former Braves pitcher and county sheriff Pat Jarvis. He said: “We had so much fun, I can’t believe it. We thought it would last forever.”

Of course, it didn’t. On New Year’s Eve of 1966, as Eddie and his wife were getting ready to head out for the night, a sportswriter got on the line with Eddie to ask: how did he feel about going to Houston? He’d just been traded to the Astros, with a player to be named later who turned out to be Sandy Alomar, for two players who wouldn’t be in the majors at the end of 1967. After 15 years with the Braves, no one had paid him the courtesy of a call to tell him the news. Mathews said: “I’ve always thought of myself being pretty macho but I cried like a baby.”

Still, after ending up his playing career with the Tigers in ’68 with a World Series title, Eddie went back to the Braves, managing them for the latter part of 1972, all of 1973, and most of 1974, which meant he was at the helm when longtime teammate Aaron set the career home run record.

During the winter after the 1989 season, the Braves hired Frank Howard to replace Mathews as their minor league hitting instructor. It was the end of Eddie’s 27 years of working for the Braves as a player, manager, scout and instructor. Once again, no one from the organization called Mathews to tell him he was being fired; this time he read about it in the morning newspapers. Upon seeing the news, he said: “I treated people good. I’ve got no regrets. I don’t know why I should even think about living life any differently. Because somebody in Atlanta thinks I drink too much? Screw ’em.”

In the summer of ’89, Mathews summed things up this way: “I’ll tell you the truth, if I went South [died] tomorrow, I wouldn’t have many regrets. I wished my father had lived to see what I did with the Braves. That’s about it. I’ve had a hell of a lot of fun. People say, ‘Slow down, aren’t you afraid of dying?’ I tell them, ‘I just want a week to apologize to everyone before I go.'”

Matthews would, in 1994, write a hard-to-find autobiography that acknowledged problems created by his drinking. A few years later, he suffered a terrible accident in the Caribbean , which some said led to his death in February of ’01.

Just loved this look at Eddie Mathews, Arne! I think he is representative of his generation, the “When It Was A Game” era of major leaguers: colorful, unpretentious, a bit salty, very honest. My tie to Mathews was the fact that he, Bad Henry, Sphanie, and the Milwaukee Braves were the match that lit the flame of my oldest brother’s love of baseball-and then passed that passion on to me, even though I was 15 years younger. The Braves were THE team to follow, long before the Twins came to town in ’61. Jim had the beautiful Hartland statues of Mathews and Spahn on the family mantle, in addition to Ernie Banks and Stan Musial. They were so perfectly done, iconic, and made you wonder about them as a boy, and about the great things they did as players. Check ’em out on EBay sometime if you’ve never seen them.

What I found striking about Eddie Mathews in this story was the fact that, besides his honesty, he had grown as a human being to admit he was angry at himself for not speaking out against bigotry. That could not have been an easy thing to confront! Today, many of us feel we live in such enlightened times, when it comes to race, tolerance. But you have to wonder: how would you have reacted to segregation, as a white person in the majority? Would we have done better than Eddie, given the same circumstances? We all like to think we could have been one of the few dissenters, standing against the racist jerks. We’ll never really know now, so I can only admire Mathews in retrospect. I am sorry he’s not with us anymore. It would have been cool to see and hear him opine on the state of the game today. I will have to add that autobiography to my bucket list!

Arne, This is a great article. It really brings out a side of Eddie Mathews that I was unfamiliar with. So many players of his era seemed haunted by their relationships with their fathers, and so many of them took to the bottle as a way to “deal” with their pain.

Great job,

Bill Miller

Great article – I’ll always remember my first big league game circa 1957 at Connie Mack Stadium. Eddie’s first at bat saw him double with a ball about halfway up that high wall in right field. The next time up the ball that he hit was about halfway up the light tower when it left the park. I’d never seen a baseball be hit that high or far.

#38 Billy Bruton CF, #4 Red Shoendist 2b, #41 Eddie Mathews 3B, #44 Hank Aaron RF, #9 Joe Adcock 1B, #43 Wes Covington LF, #1 Del Crandall C, #23 Johnny Loagan SS,#21 Wwarren Spahn, #33 Lew Burdette, #36 Bob Buhl.

What a team. My childhood heroes! Even though I a from Philly.

Also my first game at Connie Mack Stadium. Mathews hit the clock on the high score board in right cents. Aaron trip ovrer a beer bottle in left center chasing a hit and cracked his ankle. Robin Roberts got thrown out of the game contesting a triple play call in the inning before. this causing the beer bottle thrown in the outfield.

I was a fan in 1953 when the Braves came to Milwaukee, my home town at the time. I was eight years old. Ed Mathews was the first player whose name I heard. He became my favorite player along with Warren Spahn. I knew nothing about his private life, although some relative said that he was a heavy drinker. It is a shame that his hard living probably diminished his on-field productivity as well as his life.

I lost touch with the Braves when they left Milwaukee — a big mistake in my book.

My dad’s favorite baseball player was Eddie. When I was about 13 years old in 1995, I went to a baseball card convention specifically to get Eddie’s autograph for him. My parents had split and it was in LA, near my mom’s house. I didn’t know what hard living was back then, but Eddie was clearly indifferent at best to being there, wasn’t in the best of shape, and I remember a pack of Marlboros in his top shirt pocket. This backstory from 1989 puts a lot of the pieces together.

Eddie was simply a great player and it’s sort of shocking people in the farm leagues were benighted to his former excellence. I knew who he was at 13.