Tracking the Big Cat’s Trail to the Hall of Fame

June 28, 2013 by Jeff Cochran · 2 Comments

Johnny Mize set the record. He set it fair and square. In 1940 he hit 43 home runs, a St. Louis Cardinals record that would stand until 1998. Mark McGwire moved past Mize and others that year as he set a major league season record of 70 home runs. The powerful bat of McGwire brought great excitement to the game. Baseball was again taking center stage in the world of sports. Since then, however, a realization has set in. McGwire and other players, including Barry Bonds, now baseball’s all time home run ”king,” allegedly enhanced their hitting skills with andro, steroids and the like. Within the last few years, many achievements have been regarded with suspicion.

Johnny Mize set the record. He set it fair and square. In 1940 he hit 43 home runs, a St. Louis Cardinals record that would stand until 1998. Mark McGwire moved past Mize and others that year as he set a major league season record of 70 home runs. The powerful bat of McGwire brought great excitement to the game. Baseball was again taking center stage in the world of sports. Since then, however, a realization has set in. McGwire and other players, including Barry Bonds, now baseball’s all time home run ”king,” allegedly enhanced their hitting skills with andro, steroids and the like. Within the last few years, many achievements have been regarded with suspicion.

Johnny Mize was a powerfully built man, known as “The Big Cat.” Whether in the mid-’30s, when he made his debut in the majors or in the game of today, one senses Mize would be a dominant player. It’s not clear if he could have hit 43 or even 70 home runs if competing against current ballplayers. But that’s not the point. Baseball has certain tangibles and intangibles that make each era unique. Travel since the game went coast to coast has been tough on players. Until the mid-’50s, St. Louis was as far west as any major league team played. Then the game grew with the country. Teams moved from one city to another and more teams were added to both the American and National Leagues. Until the early ’60s, hitters never got to feast on expansion era pitching. In the ’90s, four teams were added to Major League Baseball, diluting the quality of pitching. So there are points in McGwire’s favor and there are points for Mize. But one thing is for sure. Johnny Mize never heard of andro.

Born in the Northeast Georgia town of Demorest in 1913, Johnny Mize thought his life’s work would be close to home. The idea of becoming a major league baseball player, never mind one of the all time greats, had not occurred to him. Tennis was his game. But while he was a student at Piedmont College, a coach saw how hard he could hit a baseball. The coach insisted Mize devote his spring to the college baseball team instead. Reluctantly, Mize did so. Soon, his talent was noticed by people outside the small Demorest college, people like Frank Rickey, brother of Branch Rickey, who helped Jackie Robinson break baseball’s color line in 1947.

Born in the Northeast Georgia town of Demorest in 1913, Johnny Mize thought his life’s work would be close to home. The idea of becoming a major league baseball player, never mind one of the all time greats, had not occurred to him. Tennis was his game. But while he was a student at Piedmont College, a coach saw how hard he could hit a baseball. The coach insisted Mize devote his spring to the college baseball team instead. Reluctantly, Mize did so. Soon, his talent was noticed by people outside the small Demorest college, people like Frank Rickey, brother of Branch Rickey, who helped Jackie Robinson break baseball’s color line in 1947.

Mize was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals, then operated by Branch Rickey, in 1930. But his baseball career was slow taking off. He had a striking physical presence but was deemed slow and injury plagued. After the 1935 season, St. Louis sent him to the Cincinnati Reds but he was back in a Cardinals uniform by spring. Then a great baseball career began.

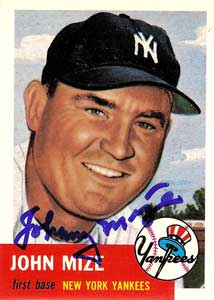

Great may be too modest a word for what Johnny Mize accomplished as a baseball player. In 15 seasons (he missed three seasons to military service, 1943-45) with the Cardinals, then the New York Giants and finally the New York Yankees, Mize presented himself as a dominating hitter and, most importantly, a smart hitter. Casey Stengel, his manager with the Yankees, said Mize was “a slugger who hit like a lead-off man.” It was with Stengel that Mize, in the last five seasons of his career, contributed mightily to five straight world championship seasons. In 1952, his next to last season, Mize hit .500 with three home runs in the World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Great may be too modest a word for what Johnny Mize accomplished as a baseball player. In 15 seasons (he missed three seasons to military service, 1943-45) with the Cardinals, then the New York Giants and finally the New York Yankees, Mize presented himself as a dominating hitter and, most importantly, a smart hitter. Casey Stengel, his manager with the Yankees, said Mize was “a slugger who hit like a lead-off man.” It was with Stengel that Mize, in the last five seasons of his career, contributed mightily to five straight world championship seasons. In 1952, his next to last season, Mize hit .500 with three home runs in the World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Despite ranking sixth among the all time home run leaders with 359 at his retirement — a total that trailed only Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, Lou Gehrig,and Joe DiMaggio — he was not accorded the recognition the game’s aficionados thought he deserved. Finally, some 28 years after he retired from the game, baseball justice prevailed. Johnny Mize was elected to the Hall of Fame.

Certainly, Mize should have felt some bitterness that it took so long to make it to Cooperstown. Bill Madden of the New York Daily News called Mize’s long wait to be voted in to the Hall of Fame “one of the game’s biggest controversies.” But on the day he was inducted into the hall, there were no hard feelings. It was time to have some fun. Mize entered the hall with his lifetime .312 average, 359 home runs and a gentle spirit that the people in his hometown of Demorest, Georgia, remember well.

Mize called Deland, Florida, home during the off-seasons and for the first twenty years after he retired from baseball. But in the mid-seventies he moved back to Demorest. The small town life appealed to him. Demorest Town Clerk Juanita Crumley remembers how Mize ”wanted to be part of the community; he wanted to interact with the people.” According to his daughter, Judi Mize, “Daddy was very shy,” but would loosen up and “talk and talk once someone brought up baseball.” During the big 4th of July celebration in Demorest, Mize would stroll over to the center of town, sign autographs for a fee and give the proceeds to the local Cub Scout troop. Both Ms.Crumley and Ms. Mize said he was a big supporter of the Scouts.

Former Georgia State Senator John Foster recalls Mize with much fondness. Along with Mize family members and then-Georgia Lieutenant Governor Zell Miller, Foster attended Mize’s Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Cooperstown, New York. Both Foster and Ms. Mize recall the great fun Mize had greeting old baseball friends and adoring fans. Ms. Mize also remembers how former Mize teammate Joe DiMaggio was aggressively pursued by the fans at the hotel in Cooperstown. Feeling protective toward their old friend, Mize and fellow Hall of Famer Ted Williams walked on opposite sides of DiMaggio to protect him from the over eager fans. That must have been a sight: Mize and Williams, both physically imposing men long after retiring from the game, guiding the Yankee Clipper through the crowd.

The memories of the day “The Big Cat” from Demorest was enshrined at Cooperstown are still joyful ones for his daughter. She recalls pitching great Bob Gibson, inducted the same day as Mize, as “a really nice guy, very funny.” Hall of Famer Stan Musial, like Gibson and Mize, a St.Louis Cardinals great, was “a hoot, and played a mean harmonica.” Ms. Mize mentions how Hall of Fame members and their families became large extended families, forming lifelong friendships and even taking cruises together.

The memories of the day “The Big Cat” from Demorest was enshrined at Cooperstown are still joyful ones for his daughter. She recalls pitching great Bob Gibson, inducted the same day as Mize, as “a really nice guy, very funny.” Hall of Famer Stan Musial, like Gibson and Mize, a St.Louis Cardinals great, was “a hoot, and played a mean harmonica.” Ms. Mize mentions how Hall of Fame members and their families became large extended families, forming lifelong friendships and even taking cruises together.

John Foster is a baseball fan, but when he speaks about Johnny Mize, the conversation is all about the friendship they shared. One day in particular stands out. Mize walked into Foster’s office in near-by Cornelia. He handed Foster a baseball he had signed recently, saying he wanted his friend to have it. A week later Mize was dead.

Johnny Mize passed away in Demorest on June 2, 1993, in the same house he was born in more than 80 years earlier. On the last night of his life, he watched the Atlanta Braves, then the defending National League champions, on television. He had always kept up with the game, loving and respecting it, despite the inevitable changes. After the Braves game ended, he went to bed and never woke up. “The Big Cat” couldn’t have planned his last night any better. It was a fitting close for the man who named his home “Diamond Acres.”

Official site of Johnny Mize: http://www.johnnymize.com/

###

Jeff Cochran worked in advertising at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution for 27 years before accepting a buy-out in the Summer of 2008. In the seventies/early eighties, he handled advertising for Peaches Records and Tapes’ Southeastern and Midwestern stores. He also wrote record reviews for The Great Speckled Bird, a ground-breaking underground newspaper based in Atlanta.

I lived in Deland, Florida when Mr. Mize was also there. His son Jimmy attended a private school, St. Andrew’s School in Tennessee, where my older brother (Bill Harlow) and I also went to high school. My father had become friends with Mr. Mize and I recall meeting him on a few occasions, he was always talkative and friendly, and would discuss the baseball games being played by the Deland teams at Conrad Park since his son, and my brother, were involved during the summer league.

Took too long to vote into the Hall. One of the all time greats!