Hardly a Miracle

August 12, 2013 by Mike Lynch · 2 Comments

Even before the Boston Braves completed their historic comeback from a 15-game deficit on July 4 to overtake the New York Giants, win the National League pennant going away and sweep the heavily-favored Philadelphia Athletics in the 1914 World Series, manager George Stallings was being called the “Miracle Man.”

After only 13 games, 10 of which the Braves lost, the team was already 10 games out of first place. On May 20, the Braves were 11 1/2 games off the pace with a pathetic 4-18 record. They reached their low point on July 4 and finished the first half of the season on July 15 at 33-43 and an 11 1/2-game deficit. But the team caught fire and won 61 of their last 77 games, earning them the moniker “Miracle Braves.”

To credit Boston’s comeback to a miracle would assume that the big man in the sky actually gave two Shiites about the Braves, which I highly doubt. So what was behind the Braves’ spectacular second-half run that wiped out a double-digit deficit and resulted in a 10 1/2-game advantage by season’s end? Well, to answer that question we first need to look at the reasons the team began the season so poorly.

They started the campaign in Brooklyn and managed to plate only two runs in as many games, and were outscored 13-2. They moved on to Philadelphia and lost two of three to the Phillies, then opened a seven-game home stand against the Dodgers, Giants and Phillies, and lost five of seven, including blowouts of 8-1 on April 24 and 11-2 on May 1. On May 7 the Braves lost to the Giants in New York to fall 10 games off the pace. At that point in the season just about everyone had a hand in the team’s dismal performance, although Stallings blamed it on the cold and damp weather.

“This is aggravating, yet it cannot last much longer,” he said. “It is bound to change, and so is the playing of the Braves bound to change for the better…Therefore, under the conditions, there is nothing for us to do but wait for good weather and a turn of the tide.”

Among the regulars only catcher Hank Gowdy and second baseman and team captain Johnny Evers were producing anything that resembled an offense. At the end of April, Gowdy was batting .370 and slugging .556, and Evers was hitting .333. The rest of the starting lineup weighed in at only .187 with an anemic .237 slugging percentage.

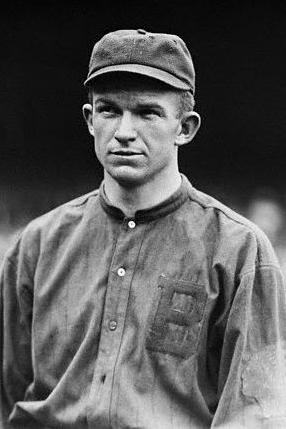

Gowdy had earned the backstop job when incumbent Bill Rariden jumped to the Federal League earlier in the year. And Evers had come to the Braves in a semi-controversial deal that was brokered by the National League after Evers insisted he became a free agent when Chicago Cubs owner Charles Murphy fired him as the team’s manager in 1913 and hired a new skipper without giving Evers the standard 10-day notice. The NL purchased Evers’ contract from the Cubs and allowed him to shop his services. He settled on the Braves thanks to a record amount that included a signing bonus, his regular salary and incentives that could top $40,000 and make him the highest paid player in baseball history if the team did well.

NL president John Tener ordered the Braves to send a player to the Cubs as compensation, and they reluctantly parted with incumbent keystone man Bill Sweeney, who finished sixth in MVP voting in 1912. Despite losing Sweeney, Braves fans and newspapermen celebrated the acquisition of Evers, who was a key cog in the powerful Cubs teams that won four pennants and two World Series from 1906-1910. In 1914, the 32-year-old veteran was paired with 22-year-old shortstop Rabbit Maranville, who was so highly regarded that he finished third in MVP voting in 1913, his first full season.

But Maranville got off to a terrible start and was hitting only .176 with little power at the end of April. The team’s best hitter, outfielder Joe Connolly, batted only .200; first baseman Butch Schmidt hit .207 with no extra-base hits; outfielder Larry Gilbert batted .200 and suffered a spike wound and sprained ankle that kept him out of the lineup for an extended period of time; and outfielder Les Mann went only 2-for-20 (.100) to start the season. Third baseman Charlie Deal was decent at .250, but battled a charley horse that would ultimately hamper him all year.

Before the month was over, Stallings changed his lineup, moving Connolly into the lead-off spot and Maranville from lead-off to third in hopes he’d be more aggressive at the plate, and benched outfielder Tommy Griffith, who was batting only .104.

The pitching was spotty as well—Dick Rudolph was the victim of terrible run support and lost his first three decisions, but he didn’t help himself, either, by allowing nine earned runs in 25 innings. Lefty Tyler lasted only five innings on Opening Day, then walked 11 batters in his second start, which he somehow won. Dick Crutcher went 1-1 and pitched to an excellent 1.57 ERA, but Hub Perdue lost both of his starts and posted an awful 8.10 ERA.

May treated the Braves better than April had, but not by much—they went 8-15 to run their record to 10-22—and the team couldn’t find any consistency. Connolly, Schmidt and Gilbert came to life at the plate, batting a combined .306 with a little pop, but the rest of the lineup hit only .222, and Hank Gowdy tailed off considerably after his hot start. Maranville continued to struggle not only at the plate, but in the field as well. After committing only two errors in nine April games, he suddenly started booting balls at an alarming rate and made 20 miscues in his next 21 games. Granted he also made plays that were among the best ever seen on a baseball diamond, but he was sporadic at best. In fact, he committed four errors in a game twice in a five-game span.

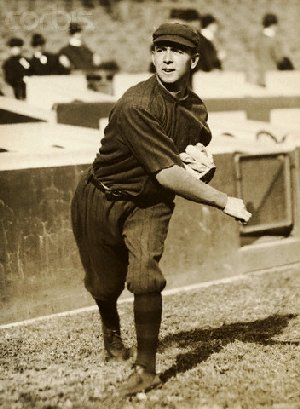

On the mound, Perdue continued to be putrid, losing both May starts and pitching to a 9.82 ERA that raised his overall mark to 9.00. “Seattle Bill” James, the team’s eventual ace, made his first appearance of the season on May 2 and was very good in seven games. He won only two of five decisions, but that was due mostly to a lack of run support—he posted a 2.76 ERA, but received only one run of support in two of his losses. Dick Rudolph also suffered from a lack of support, although he did benefit from an offensive outburst that produced 10 runs on May 4.

Ironically he won that start despite allowing six earned runs, then lost his next three decisions despite surrendering only four earned runs in 28 innings (1.29 ERA). The Braves’ offense was so anemic that Rudolph tossed 10 innings of one-run ball against Pittsburgh on May 12 only to earn a 1-1 tie when the game was called on account of darkness. The next day, James allowed only one run on two hits and two walks, but lost 1-0. Like James, Lefty Tyler went 2-3 in the month, receiving only two runs of support in his three losses. But he eked out victories of 3-1 and 3-2 and raised his record to 3-4 on the year.

May held other challenges for the Braves, most notably a battle with National League umpires, one of whom Stallings accused of conspiring against his team. According to a protest the Braves’ skipper filed with NL president Tener, Cy Rigler had been purposely making calls against his team because the arbiter was bitter after Stallings refused to sign a prospect recommended by Rigler—“He’s been throwing the hooks into my club ever since,” Stallings insisted.

Tener rejected the protest and the Braves continued to have run-ins with umpires throughout the season, although no more than the rest of the league. The Braves ranked fourth of eight in ejections, and most of that was due to Johnny Evers acting as Stallings’ right-hand man on the field. No other player earned more ejections than Evers’ 9 and only Giants manager John McGraw had as many.

The Braves started June by losing six of eight, and were 13 1/2 games out of first on June 8. Stallings lamented a lack of productive hitting by his outfielders, then sent Griffith to Indianapolis of the American Association. On June 9 the team took off and finally showed some life, winning 12 of their next 16 and trimming their deficit to 10 games. Larry Gilbert returned from his injuries in a big way and slammed four homers in a seven-game span, and Joe Connolly matched Gilbert’s home run power and led the team with a .614 slugging percentage. Maranville’s move to third in the order also paid off, as the diminutive shortstop batted .312 during the month.

Alas the team couldn’t maintain their pace and finished June in last place, 11 1/2 games off the pace. Tired of Hub Perdue’s ineffectiveness and his lack of outfield depth, Stallings sent the hurler to the St. Louis Cardinals on June 28 for outfielder Ted Cather and utility man Possum Whitted. Cather wasn’t a very good outfielder, but he batted right-handed and had a .273 average at the time of the deal. Whitted, also a right-handed hitter, was hitting only .129 at the time, but could play almost every position on the field without embarrassing himself.

Being right-handed also had its advantages; Stallings struck on an idea one night while lying in bed and revolutionized the game in the process. It occurred to the Braves’ skipper that there was no reason he couldn’t mix and match his outfield according to the handedness of the opposing pitcher, much like managers used pinch-hitters. Stallings was reluctant to start left-handed slugger Joe Connolly against southpaws, and though he earned some playing time when a lefty was on the hill, he sat more often than not.

“This event had tremendous impact on other managers,” wrote Bill James in The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers , “almost revolutionary impact, as opposed to evolutionary. Managers had platooned, a little bit here and there, since the 1880s, but it was very rare, the sort of thing that somebody would try once or twice a decade for a few weeks. From 1915 to 1925, basically all major league teams platooned at one or more positions.”

Regardless of the additions, the Braves began July with a five-game losing streak that dropped them to a season-worst 15 games back on July 4. After blue laws forced them to take Sunday off, the team began it’s magical run at the pennant on July 6 with a double header sweep over the Dodgers in Brooklyn. The Braves went home to Boston and continued to win, taking 12 of their next 16 games, including six straight, and pulled to within 11 games of the first-place Giants.

They lost the first game of a 14-game road trip, then reeled off nine straight victories, and sat only six and a half games out of first on August 6. To understand how the Braves were able to turn it around, one only needs to look to the pitching staff, most notably the trio of Bill James, Dick Rudolph and Lefty Tyler. With the exception of Les Mann, who finally began hitting the ball after three months of struggles, and Johnny Evers, nobody was lighting up opposing pitchers, and the team managed to hit all of two home runs in July.

But James won five of six decisions and posted a 1.53 ERA in almost 60 innings, and enjoyed a 22-inning scoreless streak from July 17 to the 27th that followed an incident in which he accosted a sportswriter for criticizing him in the papers. Rudolph lost his first start of the month, then began a winning streak that saw him win seven straight to close out the month. He posted a 1.88 ERA in July and ran his record to 13-8 on the year. Tyler went 4-2 with a 1.41 ERA, and allowed only two earned runs in his last 34 1/3 July innings. Dick Crutcher tossed a shutout at Brooklyn on July 6 to help the cause.

The Braves’ winning streak came to an end on August 7 with a 5-1 loss to Pittsburgh that followed sad news that Evers’ daughter Helen had died of scarlet fever. Newspapers reported that Evers was done for the season, but Stallings had received word from his second baseman that he’d be back with the team sooner rather than later. The Braves responded to the tragedy by embarking on an eight-game winning streak that launched them into second place, only three games out of first.

As the team continued to climb the standings the city of Boston began to take notice; they played in front of the largest crowd in franchise history when approximately 20,000 fans came out to Fenway Park to watch them take on the Cardinals on August 1. Red Sox president Joe Lannin, realizing the South End Grounds would be too small to handle the larger crowds, offered the Braves the use of Fenway for the rest of the season.

For the second straight month, the hitters provided little—Joe Connolly paced the squad with a .512 slugging percentage and belted two of the team’s four home runs, and Ted Cather batted .357, but the team hit only .239 in August and slugged .320. But their pitching continued to be exceptional. Bill James won seven of eight decisions and allowed only nine earned runs in 75 2/3 innings for a stellar 1.07 ERA. Dick Rudolph extended his winning streak to 12 with five straight wins before losing his last two starts of the month, and posted a 2.40 ERA. Lefty Tyler went 4-1 with a tie and pitched to a 1.11 ERA, and had a streak of 23 scoreless innings from August 11-15. And little-used southpaw Paul Strand was brilliant out of the bullpen, winning three games and allowing no runs in four appearances.

Stallings strengthened the team by purchasing third baseman Red Smith from the Dodgers on August 10 and replacing a still struggling Charlie Deal. Smith had enjoyed good seasons with Brooklyn in 1912 and 1913, when he paced the senior circuit with 40 doubles, but he’d slumped in 1914 and through 90 games was batting only .245. Smith struggled in August, but proved to be valuable down the stretch.

In his weekly newspaper column, John McGraw, manager of the first-place Giants, wrote that he wasn’t all that worried about the Braves. “I think the Braves have a better chance than the Cardinals [of ousting the Giants atop the standings], but even they cannot keep up their spurt for the simple reason that pitchers Rudolph, James and Tyler cannot stand it.” Stallings had a few words of his own about their upcoming series with New York, though. “You may safely bet that the Giants are worrying more about the outcome of this series than we are,” he said.

By the end of the month, McGraw was changing his tune and accused the rest of the National League of throwing their poorer pitchers against the Braves, who had surged to within a half-game of first place. Rather than crack under the strain of a full workload, the Braves trio of hurlers continued to roll along in September and finally got some help from the offense. The team won 26 of 31 games and by the end of the month held a 10-game lead over the second-place Giants.

The Braves hit .300 as a team and averaged 5.9 runs per game. As usual, Connolly was the team’s best hitter, posting a .990 OPS, but Red Smith also established his presence with a .355 average, a team-leading three homers and a .525 slugging percentage. Les Mann hit .333 and slugged .500 in a platoon role; Ted Cather hit .323 as a part-timer; Butch Schmidt hit .315 and Possum Whitted hit .293.

Rudolph followed his two-game end-of-August losing streak with a nine-game winning streak, giving him a 21-2 record since July 6, and he posted another very nifty ERA of 1.56. James was almost as good, going 7-1 with a 2.05 ERA, and though Tyler couldn’t keep up—he went 3-3 with a 3.72 ERA—the staff got a nice boost from George “Iron” Davis, who tossed a no-hitter against the Phillies on September 9.

They finished the season by winning five of eight to finish at 94-59, 10 1/2 games better than the Giants. Stallings threw Tyler, James and Rudolph once each, but held them to three innings apiece in what were clearly tune-ups for the World Series. James and Rudolph continued to dominate in the Fall Classic, winning two games apiece and combining for only one run in 29 innings, a spectacular 0.31 ERA, in a four-game sweep over Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s.

During the regular season, the Braves didn’t excel in any one area, but they were better than average in most. On offense the only category in which they led the league was walks, but only the Giants scored more runs and only the Giants and Phillies scored more runs per game than Boston’s 4.16, which was almost a third of a run better than league average. The pitching staff led the league in wins (obviously) and complete games, and was second in shutouts and innings, but they landed in the middle of the pack in ERA and were only .04 runs better than average. The team’s defensive efficiency—their ability to turn batted balls into outs—was also in the middle of the pack, but slightly better than league average.

Individually only a few players stood out from the rest of the league. Joe Connolly finished among the top 10 in several offensive categories, and only Phillies slugger Gavvy Cravath had a better OPS+ than Conolly’s 159. Johnny Evers finished third in the NL in sacrifice hits (31), fourth in walks (87) and ninth in runs (81); and though Rabbit Maranville led the league in outs made (469), he also finished eighth in RBIs with a career-high 78.

Bill James led the league in adjusted pitching runs and adjusted pitching wins, and James and Rudolph finished in the top 10 in most pitching categories. Tyler finished fifth in strikeouts per 9 innings, and sixth in both strikeouts and shutouts.

Defensively the Braves were very strong up the middle. Hank Gowdy led all catchers in errors with 21, but was also second in putouts and assists, and threw out almost 50% of opposing basestealers (49.7%). Evers was fourth in putouts and fifth in assists, and paced all NL second sackers with an excellent .976 fielding percentage. Maranville was a superstar with a glove on his hand; not only did he lead all shortstops in assists, but led the entire league and it wasn’t even close, as he finished 99 assists ahead of the runner up, and 100 ahead of the next best shortstop. And though he committed a league-worst 65 errors, Maranville led the league in putouts, double plays and range factor by wide margins, and made several spectacular plays throughout the season. Les Mann held down center field with aplomb, leading all center fielders in assists (24) and double plays (8), and finishing fifth among all outfielders in range factor (2.41).

In a close race Evers edged Maranville in MVP voting, 50 to 44, and James came in third with 33 votes. Rudolph finished seventh and Butch Schmidt came in 16th, but Connolly received no votes despite carrying the offense on his back. Interestingly, though Evers’ teammates were happy for him, most Braves felt Maranville deserved the award.

A closer look at the Braves and the rest of the National League illuminates the keys to their success:

- Leadership : George Stallings earned a reputation for coaxing the most out of his players; in fact, during the NL’s winter meetings following the Braves’ World Series victory he was perplexed as to why no one was willing to acquire the players he was shopping. Eventually word came out that other managers were fearful that they wouldn’t get the same production from those players that Stallings got. It was reported in papers that Stallings had driven the Braves to a “contending position for the pennant by sheer force of his invectives.” Another paper wrote, “Stallings’ words sting at first, but they have no ill after affect.”

He also worked his troops hard and it showed in the second half of the season. On April 30, after two straight days of rain, Stallings had his team take an hour of batting, then pitted them against each other in a 14-inning practice game. And when Red Smith came over from Brooklyn in August, he was shocked to learn that the Braves held morning workouts on game days.

And, of course, he had veteran second baseman Johnny Evers on the diamond serving as his field captain. Evers was in his 13th season and had played for two of baseball’s most successful managers, Frank Selee (.598 career winning percentage) and Frank Chance (.593 winning percentage) before becoming a manager himself and leading the Cubs to an 88-65 record in 1913. As mentioned before Evers led the National League in player ejections and some of them were the result of sticking up for teammates.

- Pitching : The Braves used 12 pitchers during the season, but relied heavily on only three—Dick Rudolph, Bill James and Lefty Tyler—who threw 66% of the team’s innings. The trio combined for 68 of the team’s 94 wins (72.3%) and pitched to a 2.29 ERA in 940 innings. The rest of the staff was led by Dick Crutcher, who tossed 33% of the remaining innings. Unfortunately he was subpar (5-7, 3.46) as was the rest of the staff except for Paul Strand (6-2, 2.44).

The nine pitchers not named Rudolph, James or Tyler posted a 3.63 ERA, which was almost a full run (0.85) above league average. After Crutcher the only other pitcher who threw more than 56 innings was 35-year-old journeyman southpaw, Otto Hess, who went 5-6 with a 3.03 ERA.

Despite John McGraw’s prediction that the big three would eventually succumb to the strain of too much work and pressure, they carried the team throughout the season, especially in the second half when they went 45-7 with a microscopic 1.65 ERA in just more than 500 innings.

Eventually they all succumbed to arm trouble, and though Rudolph and Tyler enjoyed future success, James won only five more games in his career. From 1914-1916 Rudolph threw 999 2/3 innings, an average of 330 per season; Tyler averaged 241 innings in the four seasons following 1914; James tossed only 73 2/3 innings in the rest of his brief career. It’s difficult to blame Stallings for overworking Rudolph, as he’d averaged 281 2/3 innings per year in the minors from age 19-24, and had almost 1,700 innings on his arm by age 25, his first season with the Braves.

Tyler, on the other hand, had only one and a half seasons of minor league pitching under his belt before embarking on a three-year run from 1912-1914 that saw him average 273 innings a year. Past 1914, Tyler averaged only 171 innings a year, but he was very good, going 76-54 with a 2.51 ERA in 174 games. In 1918 he went a career-best 19-8 with a 2.00 ERA for the Cubs before suffering from shoulder trouble.

James had one year of minor league experience with the Seattle Giants in 1912 and threw only 135 2/3 innings in his first major league season before tossing 332 1/3 frames in 1914. He experienced arm fatigue in 1915 and was able to throw only 68 1/3 innings that season, and was effectively finished at the age of 23.

It’s interesting to note that the Braves pitcher who enjoyed the most success after 1914, was “The Pride of Havana,” Dolf Luque, who went 194-178 for the Reds, Dodgers and Giants from 1918-1935 (he threw only 8 2/3 innings for the Braves in 1914).

- Strength Up the Middle : As I mentioned before the Braves were extremely strong up the middle, which may or may not be crucial to a team’s success, but that’s beside the point. Hank Gowdy ranked fourth among NL catchers in defensive Wins Above Replacement, but no senior circuit backstop had more Win Shares, and only Wally Schang and Ray Schalk had more among all major league catchers (I choose not to count the Federal League because of their inferior quality of competition).

He ranked second in putouts and assists, third in caught stealing and fourth in caught stealing percentage. He had only one good month of batting, but was the team’s hitting star in the World Series, batting .545/.688/1.273 in the four-game sweep.

Second baseman Johnny Evers led all second basemen in defensive WAR (1.8), and NL second basemen in total WAR (4.8) and Win Shares (24.0), and his .976 fielding percentage was the fourth best among keystone men since the forming of the National League. His hitting was inconsistent throughout the season, but his 114 OPS+ was second among the team’s regulars behind only Joe Connolly.

Rabbit Maranville’s defensive numbers were otherworldly and still among the best at the shortstop position. His 574 assists and 92 double plays are Deadball Era records, and he ranks third in single season putouts. In fact his 407 putouts are third in baseball history, and his assist total ranks ninth all time. His defensive WAR (4.2) was head and shoulders above the pack—Senators shortstop George McBride was second at 3.0—and he was number one among shortstops in total Win Shares and fielding Win Shares. He wasn’t one of the team’s better hitters, but he led them in RBIs with 78 and steals with 28, and was second in runs (74) and hits (144).

Les Mann was also a subpar hitter, but played a very good center field as described by the Boston Globe’s J.C. O’Leary. On May 1, Giants center fielder Bob Bescher drove a ball to deep center field in the second inning that looked like it would surely go for extra bases and plate at least two runs. “No one thought he had a chance to touch the ball,” wrote O’Leary of Mann. “He got away fast on his sprint, however, and as the ball was apparently about to sail over his head, he shot up into the air, shoving his hand up to full reach.” Mann failed to secure the ball on his initial stab, but gathered it in before his feet hit the ground.

Mann was among the league leaders in assists (24), double plays (8) and range factor (2.41), and Possum Whitted, who spelled Mann in center field from time to time, was equally effective, fielding at a .967 clip and gathering in balls with a 2.32 range factor.

- Acquisitions : The team took a hit before the season started when spitballer Jack Quinn jumped to the Federal League to pitch for the Baltimore Terrapins despite already having signed a contract to pitch for the Braves. Stallings had Quinn penciled in as his ace, and sued the Federal League, the Terrapins organization and its officers. The suit was dropped after the Braves’ success proved the loss of Quinn didn’t harm their organization.

The first significant deal Stallings made (there were no General Managers back then, so managers made trades) was to send pitcher Hub Perdue to the Cardinals for Ted Cather and Whitted on June 28. Perdue turned his season around and went 8-8 with a 2.82 ERA for St. Louis, but the Braves didn’t miss him. Cather, on the other hand, provided very good offense for Boston, batting .297/.338/.400 with a 116 OPS+, and filled in at all three outfield positions. Whitted wasn’t as strong offensively (.261/.326/.376), but he played five different positions and allowed Stallings to sit his left-handed batters against tough southpaws.

Less than a week later, Stallings added another outfielder when he sent infielder Jack Martin to the Phillies for former Giants star Josh Devore. The trade ended up being a wash, as neither really added much to their new respective teams.

The transaction that helped the Braves most was the purchase of third baseman Red Smith from Brooklyn on August 10. Smith was struggling with Brooklyn, hitting .245/.310/.361, but had driven in 48 runs in only 90 games, and was one of the better third basemen in all of baseball—he ended up leading all hot corner men in assists, double plays and range factor, and was only one putout from tying for the lead in that category as well.

Incumbent third sacker Charlie Deal was the worst hitter on the team, batting .210/.270/.276 with a 60 OPS+ in 79 games, and though Smith got off to a slow start and hit only .227/.271/.288 in his first 66 at-bats with the team, he infused new life into the Braves down the stretch by hitting .355/.448/.525 with a team-leading 50 hits, 15 doubles, three homers and 24 walks. Unfortunately he broke his ankle at the end of the season and missed the World Series. Deal filled in for the Fall Classic and was typically ineffective at the plate, hitting .125.

- Platooning : Stallings wrote after the season that when he began platooning his outfielders in July, Joe Connolly heated up and began producing the way he was expected to. Granted, Connolly was better in the second half of the season (.330/.406/.519) than in the first (.278/.345/.460), but it’s not necessarily because he stopped playing against southpaws. In fact, his batting average was identical (.306) in games started by both lefties and righties; he had a better on-base percentage in games started by lefties (.405 vs. .375), but a better slugging average in games started by righties (.499 vs. .417).

Because I don’t have play-by-play data some of the above numbers (especially on-base average) aren’t 100% accurate, but they’re very close. And I can all but guarantee that some of Connelly’s hits in games started by lefties came against right-handed relievers, which has inflated his stats vs. portsiders. Still, it’s interesting to note that Connolly had more at-bats against lefties after Cather and Whitted joined the team than he did before Stallings had multiple right-handed options.

That said, Stallings was definitely on to something—Mann, a righty, was much better against southpaws (.298/.349/.431) than against righties (.202/.239/.327); Whitted, also a righty, had the same sort of success against lefties (.306/.366/.402), but was far less effective against righties (.233/.287/.308); Cather, a righty, had a better average against lefties (.310) than righties (.267), but slugged .422 against righties and only .390 vs. southpaws; Devore, a left-handed batter, was actually more effective against southpaws, but in a small sample size; and Gilbert, another left-handed batter, was far more effective against southpaws (.299 average and .478 slugging) than against righties (.255 AVG, .325 SLG), but also in a small sample size.

- The Rest of the NL : In the 10 year period from 1904-1913, the National League was dominated by the New York Giants, Chicago Cubs and Pittsburgh Pirates, who accounted for all 10 pennants. The Giants won five pennants and averaged 97 wins a year; the Cubs won four pennants and averaged almost 99 wins a year (98.6); and the Pirates won one pennant and averaged almost 92 wins a year (91.7). Only twice in that span did a first-place team fail to win 100 games—in 1908 and again in 1911—but the pennant winners both won 99, and in 1908 the top three teams won 99, 98 and 98, respectively. It wasn’t until 1913 that the second-place team failed to win at least 91 games.

The balance of power shifted dramatically in 1914 and the Braves clearly benefited most. After winning four pennants and two World Series from 1906-1910, and averaging 106 wins a year, the Cubs began to slide in 1911, and by the end of 1914 they were a fourth-place team who finished only two games over .500. The Giants were coming off three straight pennants and three World Series losses, and averaged 101 wins from 1911-1913, but managed only 84 wins in 1914. The Pirates had been less consistent than the other two powerhouses—they went from 98 and 110 wins from 1908-1909, to 86 and 85 from 1910-1911, to 93 in 1912, to 78 in 1913. By the time the 1914 season wrapped up, the Pirates found themselves in seventh place with a record of 69-85, and their .448 winning percentage was their worst since 1891.

The Giants had the oldest pitching staff in the league, and it showed. Legendary hurler Christy Mathewson went 24-13, but his days of eye-popping ERAs were over. From 1901-1913 Matty pitched to a stellar 1.96 ERA in almost 4,200 innings, but slipped to a 3.00 mark in 1914 at age 33. After averaging 24 wins a year from 1911-1914, including a league-leading 26 in 1912, 27-year-old southpaw Rube Marquard went only 12-22 with a 3.06 ERA. And Al Demaree went from 13-4 with a 2.21 ERA to 10-17 and 3.09. Only Jeff Tesreau continued his success from previous seasons, going 26-10 with a 2.37 ERA.

Had John McGraw’s hurlers been able to replicate their 1913 stats, or come close, the 1914 National League pennant race would have been much closer and more competitive.

The bottom line is the Braves overcame a slow start in 1914 thanks to spectacular pitching by their “Big Three,” an above-average offense and defense, strong leadership that got creative, excellent performances from a few key players, solid acquisitions and a shift in power that gave other NL teams a fighting chance.

Bill James pitched for Seattle in the Northwestern League in 1912. He had a 26-8 record and led the league in ERA and strikeouts. See http://sportspressnw.com/2119279/2011/wayback-machine-seattle-bill-james-and-the-1912-giants

Thanks, Cliff! I used Baseball-Reference.com, which still doesn’t have his 1912 season listed among his pitching stats. Whoops.