Henry Aaron: A Superstar Who Spans the Generations

June 6, 2014 by John Brieske · 4 Comments

For those of us who have lost our dads, Father’s Day is tough. While it can mean spending time with our own children, it also reminds us of a hole in our lives that can’t be filled. Sometimes, the best we can do is to cherish memories of the good things that we shared with our fathers. Something that my father and I shared was an admiration, love and maybe a little hero worship for our favorite baseball player: Henry Aaron.

For those of us who have lost our dads, Father’s Day is tough. While it can mean spending time with our own children, it also reminds us of a hole in our lives that can’t be filled. Sometimes, the best we can do is to cherish memories of the good things that we shared with our fathers. Something that my father and I shared was an admiration, love and maybe a little hero worship for our favorite baseball player: Henry Aaron.

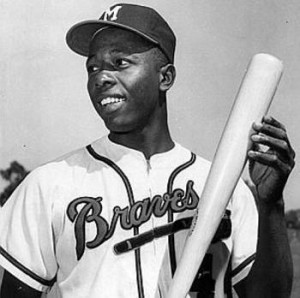

Because Hammerin’ Hank was a cross-generational hero, it takes time to tell this story. In 1953, the Braves left Boston and brought major league baseball to Milwaukee. The following year, a skinny, 20-year-old kid from Mobile, Ala., replaced an injured Bobby Thomson and hit .280, slammed 13 homers and knocked in 69 runs during a rookie season that was the first step toward a first-ballot spot in Cooperstown and a crowning as the sport’s all-time home run king.

That skinny kid, of course, was Henry Aaron. Tom Brieske, another kid living in Milwaukee, had a new baseball hero. My late father was 13 when Aaron broke into the lineup and began a long-distance relationship that lasted for decades and was passed down to at least two generations.

As Aaron quickly grew into one of baseball’s shining stars and the Braves became a contender in the National League, my father’s admiration for his hero also grew. He told me that one of his fondest teenage memories happened on Sept. 23, 1957. My father and some of his friends were playing hoops at a neighborhood schoolyard basketball court and listening to a transistor radio as the Braves battled the Cardinals in a tight ballgame with the National League pennant on the line. After Aaron blasted a walk-off, two-run shot in the 11th inning to clinch Milwaukee’s first NL pennant, he was mobbed and carried off the field by his teammates. Several miles away, Brieske and his friends let loose some celebratory shouts with the kind of unbridled joy that only teenage boys can unleash.

Aaron, who was named the National League MVP that year, hit .393 with 3 homers and 7 RBI as the Braves beat the invincible Yankees in seven games to win the World Series and send Milwaukee residents into a frenzied celebration.

Although the Braves made it to the World Series in 1958 (they lost in a rematch with the hated Yanks) and contended for the pennant for several years after that, 1957 was Milwaukee’s brightest baseball moment for the Braves and for Brieske. Times were changing. The kid, now 18, would soon head to San Antonio, Texas to attend college, and Aaron would never play in another World Series.

After graduation, Brieske got married, had three sons and earned two graduate degrees. During that time, Brieske’s family lived in four cities in three states and the championship Green Bay Packers replaced the Braves as Tom’s team of choice. While he followed Aaron’s march of consistent greatness from afar, it just wasn’t the same, particularly after the Braves abandoned Milwaukee for the lure of the Sun Belt and new money of Atlanta in 1966.

By the summer of ’69, Tom and Henry weren’t kids anymore. Brieske was almost 30 when he moved his family to Atlanta and took a job as a math professor at Georgia State University. The fast-growing city was a foreign place to the Milwaukee native, but a familiar face welcomed Brieske to Atlanta. At 35, Aaron was still terrorizing pitchers during the stretch run of a season in which he hit .300, belted 44 homers, drove in 97 runs and led the Atlanta Braves to their first division title.

My dad took my brothers and me to our first Braves game that season. Actually, it was two games — a doubleheader against the Giants. I was only 6 so I don’t remember too much about that day except that it was long and hot and it was the first time that my father told me about Henry Aaron. When Willie Mays came up to bat, he said that the flashy center fielder was one of the best to ever play the game. But then he pointed to right field and told us that HIS favorite player was the great Henry Aaron. As he recounted some of his memories of watching Aaron play in Milwaukee, I adopted my first boyhood baseball hero: Henry Aaron, the same as my dad.

I didn’t realize it then, but sharing Aaron with my dad was the start of our baseball bond. When we watched Braves games on TV or at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, he always made sure I paid attention to the great hitter. He needn’t have worried; I studied Aaron very closely. I loved the way he got down on one knee in the on-deck circle and watched the pitcher intently, like a regal lion eyeing his prey. When it was his turn to hit, the great man slowly strolled to the batter’s box — calm, cool and confident. He always carried two bats in one hand and a batting helmet in the other, dropping one bat on the way to the box before stopping to put on his helmet. He would dig in, take three perfect practice swings and get ready to hit. He always seemed like the most relaxed person in the ballpark.

There was a good reason for that demeanor.

“The pitcher has got only a ball. I’ve got a bat. So the percentage in weapons is in my favor and I let the fellow with the ball do the fretting,” Aaron was once quoted as saying.

His calm hid the fierce competitiveness that burned deep within.

“I never smile when I have a bat in my hands. That’s when you’ve got to be serious,” he told the Milwaukee Journal in 1956. “When I get out on the field, nothing’s a joke to me. I don’t feel like I should walk around with a smile on my face.”

As boys who love baseball often do, I copied Aaron’s every move when I strode to the plate during pickup baseball games at the neighborhood park or when we played Wiffle Ball in the front yard. Sure, I had my other hitter imitations – Willie Stargell’s windmill, Joe Morgan’s elbow flap and Pete Rose’s crouch-and-peek over his shoulder – but there was nobody like “Bad Henry.”

The man was so cool. Even his number – 44 – was perfectly symmetrical and just looked great on the back of a jersey. In fact, Aaron hit exactly 44 homers in a season four times during his 23-year career. I’m convinced that was no coincidence.

As a fan of Georgia sports for more than 40 years, I’ve been lucky enough to witness some great moments in person. I was in the stands with one of my brothers in 1995 when Tom Glavine pitched a 1-hitter and Dave Justice belted a solo shot to clinch the Atlanta Braves’ only World Series title. My dad and I saw Dominique Wilkins soar, slam and shoot for 24 points in the first quarter to upstage Michael Jordan at the Omni in the late 1980s. My father and I were about 15 feet from Jerry Pate when he knocked stiff an impossible, pressure-packed 5 iron on the 18th hole to win the 1976 U.S. Open. I was privileged to walk the hallowed grounds of Augusta National with my dad as we followed Arnold Palmer, Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus as they played in the Par 3 tournament at the Masters in 2010.

But one of the coolest sports moments I ever witnessed was during a meaningless baseball game on Aug. 6, 1973. In those days the Braves visited their old home to play an annual exhibition game against the Brewers. The Brew Crew were in the American League then and this was years before interleague play, so the game gave Milwaukee baseball fans a chance to relive old memories and watch Aaron play in County Stadium again.

On that day in 1973, Aaron was 39, one of game’s elder statesmen, and only 13 homers short of tying Babe Ruth for the all-time home run record. Despite receiving piles of despicable hate mail and awful death threats from ignorant people who couldn’t stand the idea of a black man breaking the sport’s most sacred record, Aaron was still putting up superstar numbers. In only 392 official at bats, Aaron hit .301 with 40 homers and 96 RBI that year.

During our annual visits to Milwaukee, my brothers and I always attended a couple of Brewers games. But this game was special; Hank was back in town and our Braves were playing. On this night, my grandfather (also an Aaron fan), my father, my two brothers, a cousin and I were among the 33,337 fans who gathered at County Stadium. You could sense that this would be no mere exhibition game; the place was buzzing as venders hawked commemorative programs and old Milwaukee Braves fans dug into their closets and dusted off hats with the familiar “M” emblem above the bill.

According to the Milwaukee Sentinel

, Gov. Patrick J. Lucey issued a proclamation designating Aug. 6 as “Hank Aaron Day” in Wisconsin. Aaron was welcomed back in style with a motorcade down Wisconsin Avenue complete with a police escort. The stage was set for something special. Although both teams fielded lineups with some backup players, it didn’t matter; the man of the hour was Aaron. I was 10 at the time and I can’t remember what he did during his first two at bats, but I’ll never forget the third one.

According to the Milwaukee Sentinel

, Gov. Patrick J. Lucey issued a proclamation designating Aug. 6 as “Hank Aaron Day” in Wisconsin. Aaron was welcomed back in style with a motorcade down Wisconsin Avenue complete with a police escort. The stage was set for something special. Although both teams fielded lineups with some backup players, it didn’t matter; the man of the hour was Aaron. I was 10 at the time and I can’t remember what he did during his first two at bats, but I’ll never forget the third one.

When Bad Henry came to the plate in the 6th inning, there was a man on base and Bill Parsons, a hard-throwing righty, was on the mound. Aaron went through his familiar ritual and calmly strode to the plate as the crowd gave him warm round of applause. Parsons, who was the American League Rookie Pitcher of the Year in 1971, challenged Aaron and tried to blow a fastball by the aging slugger.

Joe Adcock, one of Aaron’s former teammates in Milwaukee, was once quoted as saying that “trying to sneak a fastball past Hank Aaron is like trying to sneak the sunrise past a rooster.” True to that adage, Aaron blasted that pitch from Parsons into the left field stands and rounded the bases as the crowd rose to its feet and let out a rising crescendo of cheers. Chills ran down my spine as the fans roared, stamped their feet and called for Aaron to come out of the dugout and tip his cap. He obliged us but it still wasn’t enough for the cheering crowd. He emerged again and it was only then that the 2-minute and 15-second standing ovation died down.

My ears were ringing and my hands hurt from clapping long and hard. I remember my dad saying that Henry Aaron belonged more to Milwaukee than to Atlanta. Being an Atlanta fan, I didn’t agree with him; I wanted to claim him for my own. Years later, I realized that my father was right. He was always right about those types of things.

In the Milwaukee Journal the next day, Aaron was quoted as saying, “I came back after eight years and they were standing up over two minutes for me. That brought tears to my eyes.”

He wasn’t the only misty-eyed person in the ballpark that night. I watched as my grandfather and father smiled, cheered and wiped away tears. My father kept saying, “Did you see that? Did you see that?” – almost as if it didn’t really happen. But it did. Three generations of Brieskes saw Bad Henry bring down the house one more time.

I didn’t grow up with any sisters and I don’t have daughters, so you’ll have to forgive me when I say that baseball has always been about fathers and sons. As far as I’m concerned, any man who claims he doesn’t get choked up when watching the scene in “Field of Dreams” in which Kevin Costner’s character plays catch with his father’s younger self is either lying or has no soul.

Like many dads, I read bedtime stories to my two sons when they were little boys. I read the classic stuff, but I sometimes told them stories that I didn’t need a book to recite. I told them about a skinny kid from Mobile, Ala., who overcame the odds and the most virulent forms of racism to become the sport’s all-time home run king.

When my father and I took my boys to an Atlanta Braves game on April 8, 1999, it was a celebration of the 25th anniversary of Aaron hitting his 715th home run to break Babe Ruth’s record. More than 47,000 fans rose to their feet to give the great man a standing ovation as he coolly strode to the podium during pregame ceremonies at Turner Field. Aaron had once again brought three generations of my family together, this time adding a new one to the mix. I know that if I ever have a grandson – or a granddaughter for that matter – I will tell bedtime stories about number 44 and the great man who, once upon a time, hit 755 dingers to beat them all. After all, it’s a family tradition.

Well done, John! I really enjoyed reading the article and recounting that earlier time.

John, I love this article. Thanks for sharing your memories of two greats — Hank and Tom.

@Kregg Johnston – That was quite an outfield the Braves had back in the early 70’s: Ralph Garr, Dusty Baker, and anchored by the legend Hank

Aaron.

Great Job! Leo’s Hank Aaron signed baseball will now have a greater meaning as a family heirloom knowing this story of Tom and the Brieske boys.Uncle Pat