The Improbable Career of Adolph “Otto” Rettig

July 31, 2014 by Dave Heller · Leave a Comment

The St. Louis Browns had never seen the Philadelphia Athletics starter previously, someone who was listed as “Rettiz” in the scorecard.

The St. Louis Browns had never seen the Philadelphia Athletics starter previously, someone who was listed as “Rettiz” in the scorecard.

There was some of the usual razzing of the unknown rookie, but that soon stopped as batter after batter was fooled by the newcomer’s “slow ball.”

It was July 19, 1922, and Adolph “Otto” Rettig had literally stepped off the train and onto the mound to beat the first-place Browns. His path even getting to that spot was as improbable as his landing point.

There have been many improbable careers in Major League Baseball, but how Rettig ended up appearing in the majors might just top any of them.

Rettig had pitched for Seton Hall before entering the professional game in 1914 with Pittsfield of the Eastern Association, where he went 10-12 in 1914.

Pittsfield sold Rettig to Troy of the New York State League, but that club released him in May. Rettig ended up with Lewiston of the New England League, posting a 12-13 record in 30 games in 1915.

Here’s where things, as often happens when looking back nearly 100 years, get a little murky.

It is clear that Rettig was sold to Lynn of the Eastern League for the 1916 season but failed to report, thus causing him to be suspended. “Rettig states that he would rather play Sunday baseball in New Jersey than stay with the Lynn club,” reported the Lowell Sun.

The June 17, 1916 edition of The Sporting Life reported that Rettig—now going by the name Otto—signed his contract with Lynn. But that apparently was false information because there is no record of him playing and in November he was once again listed on the team’s suspended list.

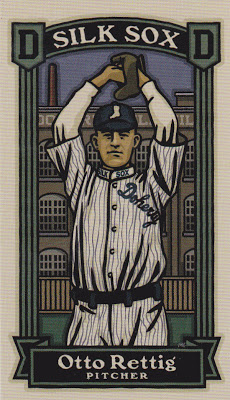

Instead, Rettig joined a semipro team—the Doherty (N.J.) Silk Sox. As it turned out, Rettig got to pitch to major leaguers on Oct. 1, 1916 when the New York Giants played an exhibition against the Silk Sox in Paterson, N.J. Rettig pitched for the Silk Sox despite having pitched the previous day. According to the book The Major League Pennant Races of 1916, the Giants used all their starters except at catcher and pitcher (Hank Ritter, who appeared in three games for the Giants in 1916, was on the mound for New York), and were even offered monetary bonuses for the amount of runs they scored and any home runs hit. However, Rettig tamed the Giants, winning 2-0, allowing only three hits while striking out 13.

It was reported that Rettig signed with Springfield of the Eastern League for 1917, but, while a later Sporting News article would claim he had “a successful season” with that club, there is no record of him ever pitching for Springfield. Supposedly, again according to that TSN article, Rettig was sold to the Boston Red Sox, but refused to report because he wanted “a percentage of the purchase price.” (In fact, this story was told in articles which appeared in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.)

It is more likely that the situation described above was what occurred when Rettig was sold to Lynn. Later reports through the years would claim Rettig was suspended by organized baseball and never should have pitched for the A’s, but he never appeared on a suspended list after 1917.

From 1917 up until his debut with the A’s, Rettig pitched for semipro teams in New Jersey.

However, he had continually been angling to get a shot at the majors. Frank Bruggy had joined the A’s in 1921 and was a teammate of Rettig’s at Seton Hall. The two remained in communication and Rettig would express his desire to Bruggy, who in return would pitch the idea to A’s manager Connie Mack.

Perhaps Mack acquiesced and told Bruggy to bring in Rettig for a trial to shut him up, or maybe he was serious about giving Retting a look. Either way, Rettig got on a train and arrived at Shibe Park at 2 p.m. on July 19.

Perhaps Mack acquiesced and told Bruggy to bring in Rettig for a trial to shut him up, or maybe he was serious about giving Retting a look. Either way, Rettig got on a train and arrived at Shibe Park at 2 p.m. on July 19.

Pitching that day for the Browns was Urban Shocker. As it turns out, Shocker had the A’s number over the years. In 1919 vs. Philadelphia he was 3-0 with a 0.43 ERA. In 1920, 3-0 with a 1.64 ERA. In 1921, 5-1 and 1.33, and in his lone start against the A’s in 1922 back on May 12 in Philadelphia, he won again, pitching a complete game while allowing three earned runs and striking out eight.

Faced with that, Mack gave in and one hour after stepping off a train, Rettig was put into the lineup as the starting pitcher for the A’s.

The Browns did take an early 2-0 lead, scoring once in the first and fourth innings, but using his “slow ball,” Rettig kept St. Louis hitters off balance. The A’s finally solved Shocker, who allowed a pair of two-run home runs to Tilly Walker, and Rettig went the distance in a 6-3 win, allowing nine hits while walking two and striking out two.

In later years, it would be “remembered” that Rettig won 8-0 both in a 1932 cartoon/article (which also claimed Rettig threw a two-hitter) and by former A’s outfielder Bing Miller.

After this loss, Browns vice president Walter Frisch decided to loosen things up and threw a team party. “He bought cigarettes, mints (untouched) and a few other things, took the boys to his suite of rooms and told them to sing, talk and yell about anything about baseball,” reported the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

At the party that night, writer J.C. Kofoed talked to Browns star George Sisler (who went 1-for-2 with three walks) about Rettig.

“I’ll make a little bet that this fellow, Rettig, doesn’t win another ballgame from us, and another that he loses half a dozen more before he wins again,” Kofoed reported Sisler as telling him.

Sisler wasn’t too far off.

It took a week, but Mack eventually signed Rettig to a one-year contract and he boarded another train—this time with the A’s as they headed west. Philadelphia opened with a doubleheader in Cleveland on July 25. Rettig pitched the next day and was actually even better than the first time he pitched. He allowed just four hits and two runs in seven innings—walking two and striking out two—but the A’s couldn’t score off George Uhle despite seven hits and six walks.

Rettig earned another shot and it came five days later in Detroit. But he wasn’t able to fool the Tigers, who pounded him for five hits and six runs (five earned) in 2 1/3 innings. Rettig also walked three and didn’t strike out a batter in Detroit’s 11-1 victory.

Nevertheless, Mack started Rettig again five days later in St. Louis. Rettig walked Wally Gerber and Jack Tobin to start the game and then took a walk himself—to the showers. He’d never set foot on a major-league diamond again as the A’s gave him his unconditional release.

From a wire story datelined Philadelphia, Aug. 18: “No busher in baseball-fiction ever went further with nothing on the ball, had more fun or got away with a bigger bluff than a kid pitcher whose hoax career with the Athletics has just been revealed. … Players on his own team now say that Rettig had nothing in the world but luck and the nerve of a book agent.”

While Rettig’s improbable career was quite brief, he did have an impact. The Browns lost the American League pennant to the Yankees by one game and for years the manager of that St. Louis team, Lee Fohl, blamed losing the pennant to that one defeat back on July 19 in Philadelphia.

Rettig pitched one more season of semipro ball before settling into a career as a manager for various theaters in the East Orange, N.J., area.

One might say he provided a little theatrics of his own back in 1922 just to even get in a game.