The Little Giant’s Biggest Achievement

February 28, 2022 by Frank Jackson · Leave a Comment

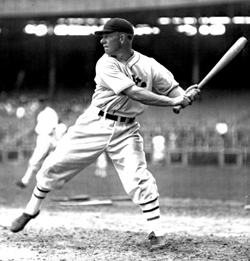

Mel Ott

requires no introduction to crossword puzzle aficionados thanks to such clues as “Hall of Famer Mel _ _ _” or “NY Giants slugger Mel _ _ _” or “Baseball’s ‘Master Melvin’ _ _ _.” Puzzle designers love prominent people with three-letter surnames. Muhammad Ali and Umberto Eco, among others, are neck and neck with Mel Ott in crossword puzzle namedropping.

Mel Ott

requires no introduction to crossword puzzle aficionados thanks to such clues as “Hall of Famer Mel _ _ _” or “NY Giants slugger Mel _ _ _” or “Baseball’s ‘Master Melvin’ _ _ _.” Puzzle designers love prominent people with three-letter surnames. Muhammad Ali and Umberto Eco, among others, are neck and neck with Mel Ott in crossword puzzle namedropping.

Among seamheads, Mel Ott is much more than just a three-letter answer in a crossword puzzle. As the first National Leaguer to reach 500 home runs, he has posthumous bragging rights in perpetuity. Curiously, he never led the league in total bases).

Also, in contrast to the two husky American Leaguers who got there before him (Babe Ruth and Jimmie Foxx), Ott stood 5’9” and weighed 170 – hence the nickname the Little Giant. Famously, the portside hitter literally kick-started his power stroke by lifting his right leg before each pitch. Those are the essentials. But there is more.

Ott was an All-Star 11 years in a row (1934-1944). If the All-Star game had been around before 1933, he surely would have been named to the NL squad several more times. He tied for the lead or led the National League in home runs six times (1932, 1934, 1936, 1937, 1938, and 1942). To accentuate that achievement, from 1929 to 1945, Ott hit 202 more home runs than any other NL hitter.

Critics point out that Ott hit the majority (323) of his home runs at the Polo Grounds. Of course, 188 home runs on the road ain’t hay, and while it’s true that Ott’s home field, the Polo Grounds, was only 257 feet down the right-field line, the dimensions flared out sharply towards center field so the power alleys were less than inviting – and forget about center field. The short porch in right field was only advantageous to a hitter who could continuously wrap his drives around the foul pole (presumably, National League pitchers pitched Ott outside to prevent him from doing so).

Ott played in three World Series (1933, 1936, and 1937) compiling a respectable slash line of .295/.377/.525 with four home runs and 10 RBIs. For good measure, he was the first NL player with more than 1,800 runs scored, 1,800 RBI, and 1,700 walks. Given all his MLB cred, it was no surprise that he was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1951.

Of course, his total of 511 home runs, struck between 1927 and 1946 has since been surpassed by numerous sluggers, some in the Hall of Fame and some not. One of Ott’s lesser-known achievements, however, was perhaps his most remarkable. Seventy-five years after he retired, no one has matched or surpassed it. One hesitates to say it was the proverbial record that will never be broken, but one could make a strong case for it. I refer to his record of 18 straight seasons (1928 through 1945) leading his team in home runs.

It’s not hard to see all the potential stumbling blocks preventing a hitter, even the most formidable slugger, from achieving this record. Let’s list a few. First of all, very few ballplayers, even bona fide sluggers, last 18 seasons. For example, Eddie Matthews and Mark McGwire both hit more than 500 home runs; the former played 17 seasons, the latter 16.

Second, injuries could easily cut into a player’s plate appearances and jeopardize a streak. Babe Ruth was the poster boy of slugging, leading his team (Red Sox in 1918 and 1919; Yankees from 1918 to 1933) in home runs every year save one. In 1925 the “bellyache heard round the world” sidelined him for the first two months of the season, limiting him to 25 round-trippers and allowing Bob Meusel to lead the team with 33.

If not for Ruth’s gastric problem (if indeed that’s what it was), he would have had a 16-season streak. Thanks to a dearth of serious medical problems, Ott never had fewer than 485 plate appearances (in 1943). During his prime years (1929-1938), he played in 97.53% (1498 out of 1536) of the Giants’ games.

Third, a streak could survive an off-season trade, as the streak could be continued with the player’s new team as was the case with Ruth. A mid-season trade, however, would likely call a halt to such a streak. This was not a problem for Ott, as he played his entire career with the Giants. Today, when sluggers are frequently shuttled from also-ran teams to contenders before the trade deadline, long-term continuity is much less likely.

Fourth, there is the pleasant problem of having teammates who are also sluggers. Among others:

Barry Bonds, MLB’s all-time home run leader (like Ott, he played 22 seasons), slugged his way through 16 seasons from 1990 through 2005. He led the Pirates in home runs from 1990-1992 and then signed with the Giants, debuting with a league-leading 46 home runs.

Then, teammate, Matt Williams hit a league-leading 43 in 1994, thus disrupting Bonds’ streak. The streak resumed in 1995 until injuries slowed Bonds in 2005 and Pedro Feliz won the team home crown with 20. Another slugging Giant, Willie Mays, had a nice streak going with the Giants but then along came Willie McCovey with 44 homers to Mays’ 38 in 1963.

Or consider Henry Aaron, who had to contend with Joe Adcock and Eddie Matthews in Milwaukee. And let’s not forget Davey Johnson (43) and Darrell Evans (41), who out-homered Aaron in 1973, even though he hit 40 at age 39.

Then there is the case of Alex Rodriguez, author of 696 home runs, who had to contend with Jay Buhner and Ken Griffey, Jr. in Seattle and Jason Giambi in New York.

Ott played with some good hitters over the years, including Hall of Famers like Bill Terry, Johnny Mize, and Ernie Lombardi, but none was able to surpass his home run total at season’s end. Candidates of lesser renown having career seasons also fell short.

When Ott made his debut with the Giants in 1926 at age 17, the team home run leader was George “High Pockets” Kelly with 13. During his sophomore year, the leader was Rogers Hornsby with 26. Ott, however, never had a chance to compete for the title.

Manager John McGraw, nicknamed the Little Napoleon, thought so highly of Ott he denied minor league managers the opportunity to tinker with him. So Ott spent the 1926 and 1927 seasons learning the game at McGraw’s knee in the Giants dugout.

The Little Napoleon mentored the Little Giant while playing him sparingly. Ott had a mere 61plate appearances in 1926, bumped up to 180 in 1927. His first major league home run (and the only one he hit in 1927) was an inside-the-park job. Of the 510 home runs that followed, all were out of the park.

In 1928 Ott took over in right field after Ross Youngs, another McGraw favorite, fell victim to kidney disease. Ott made the most of this opportunity and led the team in home runs for the first time with 18, which would prove to be his lowest total (matched in 1943) during his streak.

Was it an 18-year cakewalk for Ott or did he have serious competition? It depends on what season we’re talking about. Some years he took the lead out of the gate and never looked back; in other years, he had serious competition. Let’s take a year-by-year look at how he accomplished his streak.

1928

| Ott | 18 |

| Bill Terry | 17 |

|---|

By 1928 Ott was ready for prime time. Bill Terry was not a home run hitter (he had just 41 in 1,627 plate appearances before 1928), but Ott surpassing him in round-trippers in his first season as a regular at age 19 was a notable achievement. The Giants led the NL with 118 home runs (five players were in double figures…in addition to Ott and Terry, Freddie Lindstrom and Travis Jackson hit 14 while Shanty Hogan hit 10).

1929

| Ott | 42 |

| Travis Jackson | 21 |

|---|

At age 20, when his peers were in the minors or playing college ball, Ott had a breakthrough season at the major league level. In fact, he achieved his personal best in home runs, double the amount of his closest competitor, Travis Jackson, who was in his eighth season with the Giants. Jackson was not noted as a home run hitter, but he achieved his career-best in that regard in 1929. Jackson, a solid shortstop, played 15 seasons and finished with 135 home runs.

Though 1929 was his best season for long balls, Ott did not lead the National League in that category. Chuck Klein nosed him out with 43. Notably, Ott also led the league in walks with 113, his career-best (in one game he set a record with five intentional walks). It was the first of six times Ott led the league in walks. In fact, he garnered 100+ walks in ten seasons. His career batting average and on-base percentage were both outstanding (his career slash line was .304/.414/.533). At the same time, he rarely went down swinging. Ott’s strikeout-to-HR ratio of 1.75 places him ahead of Aaron, Ruth, Bonds, Kiner, Hornsby, and Mays. His worst showing was 69 strikeouts in 1937.

1930

| Ott | 25 |

| Bill Terry | 23 |

|---|

Ott may have been the team’s home run champ in 1930 but it didn’t come easy. As late as September 18, Terry was in the lead. That day Ott tied him with his 23 rd home run in a 6-2 loss to the Cubs at the Polo Grounds. The next day Ott hit No. 24 in a 7-0 victory over the Reds, also at the Polo Grounds, and never relinquished the lead again.

Nevertheless, Bill Terry grabbed all the headlines, as he hit .401 and remains the last National Leaguer to do so. Ott had his best full-season batting average at .349 but he wasn’t even second-best on the team, as Freddie Lindstrom hit .379. Normally, .349 would be good enough to contend for a batting title, but 1930 was an extraordinary offensive year in both leagues. The Giants set franchise records – which still stand – for batting average (.319), runs (959), hits (1,769, and total bases (2,628).

1931

| Ott | 29 |

| Johnny Vergez | 13 |

|---|

Ott had no serious challenger in 1931. You may well wonder who Johnny Vergez was. 1931 was the rookie year for this 24-year-old third baseman. His slash line of .278/.320/.396 along with 81 RBIs made for an auspicious debut.

1932

| Ott | 38(tied Chuck Klein for NL lead) |

|---|---|

| Bill Terry | 28 |

Terry had his best home run season in 1932 but it was no match for Ott’s total. It was also Terry’s first season as player-manager, so he had more to worry about than his home run total. He replaced John McGraw in June.

1933

| Ott | 23 |

| Johnny Vergez | 16 |

|---|

For Ott, his most memorable homer in 1933 was not among the 23 he hit during the regular season. Rather, it was his long ball that clinched the World Series in the top of the 10 th inning of Game 5 against the Senators. He got some help from center fielder Fred Schulte who couldn’t corral Ott’s deep drive and succeeded only in deflecting the ball over the fence.

Ott’s regular-season total was not one of his best, but he had no serious competition. Johnny Vergez could have made it interesting if not for a season-ending appendectomy on August 31. As in 1931, Vergez, though enjoying a good season, was a distant second. It was also his last hurrah. In 1934 his stats dropped off and he was peddled to the Phillies for whom had a so-so season in 1935. After that, he was a part-timer. He spent 1937 and 1938 in the minors before retiring.

1934

| Ott | 35(tied Ripper Collins for NL lead) |

|---|---|

| Travis Jackson | 16 |

As prolific a slugger as Ott was, he led the National League in RBIs only once with 135 in 1934 when he was named to his first All-Star team (the game was played at the Polo Grounds). He had no serious competition for team home run leader, but Ripper Collins of the Cardinals chose 1934 to enjoy his best year (he also led the league in slugging with .615). Something of a late bloomer, Collins did not make his MLB debut till age 27. His MLB career lasted but nine seasons, but it was eminently respectable: 135 home runs with a slash line of .296/.360/.492.

1935

| Ott | 31 |

| Hank Leiber | 22 |

|---|

Outfielder Hank Leiber had one of his better seasons in 1935 (his career-best was 24 homers for the Cubs in 1939). His RBI total of 107was second only to Ott’s (114). Though not a household word, he played 10 seasons and finished with 101 home runs and a solid slash line of .288/.356/.462.

1936

| Ott | 33 |

| Hank Leiber, Gus Mancuso | 9 |

|---|

It was a no-sweat year for Ott, as his closest competitors were in single digits. Catcher Gus Mancuso was a rather unlikely runner-up, as he never reached double digits in home runs (just 53 long balls in 17 seasons). Despite what would seem to be a power shortage, the Giants won the NL pennant, but they bowed to the Yankees (in retrospect, it was notable as Joe DiMaggio’s first World Series) in six games.

1937

| Ott | 31(tied Whitey Kurowski for NL lead) |

|---|---|

| Dick Bartell | 14 |

Shortstop Dick Bartell was another unlikely runner-up. In 1937 he matched his career-best season (1935) for home runs with 14. During his 18-year career, he amassed 2,165 hits but only 79 home runs. In a subway series rematch, the Giants bowed to the Yankees, this time in five games. Ott hit his fourth and final World Series home run in the last game.

1938

| Ott | 36 |

| Hank Leiber | 12 |

|---|

Once again Hank Leiber finished second to Ott. The third time was not the charm. In fact, it was his last opportunity, as he was traded to the Cubs after the season.

1939

| Ott | 27 |

| Harry Danning | 16 |

|---|

Ott, who was now captain of the Giants, faced another unlikely challenger in 1939. Catcher Harry Danning may not enjoy a great deal of name recognition today but in his prime, his peers were well aware of his talents (he was a National League All-Star from 1938 to 1941). Danning chose 1939 to have his best year for home runs. His 16 home runs were part of a solid season (.313/.359/.479), and he had a similar season in 1940. After that, he lapsed into mediocrity. He remained with the Giants till he turned 31 in1942, then joined the military. He was discharged in June 1945, with arthritic knees and made no attempt to resume his playing career. He retired with a slash line of .285/.330/.415 and 847 hits, 57 of which were home runs.

1940

| Ott | 19 |

| Babe Young | 17 |

|---|

1940 was a squeaker. As of September 15, Babe Young and Ott were tied at 17. The next day Ott hit two home runs in a 7-6 loss to the Pirates at the Polo Grounds, prematurely ending the home run duel. In the remaining 13 games, neither man went deep.

1941

| Ott | 27 |

| Babe Young | 25 |

|---|

1940 was a squeaker. As of September 15, Babe Young and Ott were tied at 17. The next day Ott hit two home runs in a 7-6 loss to the Pirates at the Polo Grounds, prematurely ending the home run duel. In the remaining 13 games, neither man went deep.

First baseman Norman “Babe” Young had two and a half productive seasons (he began military service during the 1942 season) for the Giants. He was 30 years old when he returned to the Giants in 1946. After stints with the Reds and Cardinals, he retired after the 1948 season. Like many other players, he lost prime playing years to the war effort, but in 1941, his last full season before the war, he had his best year (his 104 RBIs led the team) and gave Ott a run for his money. If not for the war, he might have challenged Ott a few more times in the seasons that followed.

1942

| Ott | 30 |

| Johnny Mize | 26 |

|---|

In 1942 Ott had other concerns besides his home run totals, as he assumed the status of player-manager. The Giants finished third (85-67) in Ott’s rookie year at the helm. Johnny Mize, who was 29 years old at the time, was in his first year with the Giants after establishing himself as a slugger with the Cardinals (a four-time All-Star, he hit 158 home runs in six seasons, highlighted by 43 in 1940). He finished four HR behind Ott but was named to another All-Star squad and led the NL in RBIs with 110. Had World War II not deprived him of the 1943-1945 seasons, he might have brought an end to Ott’s record.

1943

| Ott | 18 |

| Ernie Lombardi | 10 |

|---|

18 home runs were a sub-par showing for Ott, but he was likely more disappointed in the performance of his team, as the Giants slipped to last place (55-98-3). World War II had depleted the roster, so the front office likely had no great expectations. Still, a last-place finish (the Giants hadn’t been in the cellar since 1915) was unexpected. It was pretty much a downer of a season in every respect. Though he was now 35 years old, home run challenger Ernie Lombardi was still formidable enough to be named to the 1943 NL All-Star squad.

1944

| Ott | 26 |

| Phil Weintraub | 13 |

|---|

Ott’s total of 26 home runs was a long way from his career-best, but those 26 runs he scored as a result of going deep helped him eclipse Honus Wagner as the leading runs scorer in NL history (since surpassed), which indicates how well his ability to draw walks paid off. As a manager, however, he was surely disappointed in the Giants’ 67-87 record.

Phil Weintraub was perhaps the least likely of all Ott’s competitors. Arriving in MLB as a 25-year-old rookie in 1933, he had bounced back and forth from the majors to the minors through 1938. In 1944, after a five-year absence from the big leagues, he did a second tour of duty with the Giants. At age 36, he had a career year, albeit against inferior World War II era National League pitchers. In 423 plate appearances, he had a slash line of .316/.424/.512 to go along with his 13 home runs (he had but 32 in his career). For sure the highlight of his season (and likely his career) was his April 30 performance against the Dodgers when he drove in 11 runs in a 26-8 blowout of the Dodgers at the Polo Grounds.

1945

| Ott | 21 |

| Ernie Lombardi | 19 |

|---|

Ott was surely pleased that the Giants returned to respectability, finishing above .500 at 78-74, but this was the last season of inferior World War II era MLB rosters, so it wasn’t a season to build on. Curiously, Ott had two serious challengers in the last year of his record. Ernie Lombardi, though in the waning years of an outstanding career (he had 174 home runs through 1945), mounted a serious challenge to Ott.

The big surprise, however, was sophomore Danny Gardella. Like Ott, he was a left-handed pull-hitter. At 5’7” and 160 pounds, he was even smaller than Ott. Granted, he was not facing top-tier MLB pitching but his performance turned a few heads, notably in Mexico, where Jorge Pasquel of the Mexican League was raiding big league rosters for personnel.

Gardella took the bait and Pasquel reeled him in. Consequently, Gardella, among others, was banned from major league baseball and decided to issue a legal challenge to the reserve clause. Gardella’s tale of woe is a long, well-chronicled, and oft-told story, far too complicated to go into here. Without those 18 home runs he hit for the Giants in 1945, however, he probably would not have drawn any interest from Pasquel.

Ott’s string ended decisively in 1946 when he hit just one home run (on opening day) and Johnny Mize hit 22. In fact, Ott was just 5 for 68 at the plate that year, but after all he had a bum knee, he was 38 years old, and all those front-line National League pitchers had returned from the service. Since the final years of Ott’s streak coincided with the draft-depleted NL rosters of those seasons, it is not unreasonable to assume that World War II helped extend Ott extend his streak.

With younger position players available to write into the Giants’ scorecard, Ott no longer needed to insert himself into the lineup. He was still on the active roster at the beginning of 1947 but was hitless in four plate appearances (his last appearance came as a pinch-hitter in the first game of a doubleheader against the Cardinals on July 11 at the Polo Grounds).

Having retired as a player, Ott could devote himself to his managerial duties. Unfortunately, the enhanced focus did not pay off. In 1946, the first postwar season, the Giants again finished last with a 61-93 record. Ott, however, continued to play a part in baseball lore as he inspired Dodger manager Leo Durocher to proclaim, “Nice guys!

Do you know a nicer guy than Mell Ott? Or any of the other Giants? And where are they? The nice guys over there are in last place.” For popular consumption, Leo’s proclamation was truncated to “Nice guys finish last,” and attained widespread currency, even among people who know nothing about baseball. Durocher later employed the phrase as the title of a 1975book he wrote with Ed Linn.

The Giants improved their record to 81-73 in 1947. Ironically, in the Giants’ first year without the all-time NL champ on the active roster, the team set a franchise home run record with 221 (surpassed by the 2001 San Francisco Giants who hit 235). Adding to the irony, after a 37-38 start in 1948, Ott was relieved of his duties and replaced by Leon Durocher, who had been suspended during the 1947 season for consorting with gamblers and other shady characters, as well as a marriage (to actress Laraine Day) with overtones of adultery and bigamy. No more Mr. Nice Guy, indeed!

At the time, no one knew that Durocher was extending another streak in conjunction with Ott. Starting with John McGraw in 1902, then Bill Terry in 1932, Ott in 1942, and Leo Durocher from 1948 through 1955, the New York Giants were managed exclusively by Hall of Famers. Even interim managers Hughie Jennings (1924-1925) and Rogers Hornsby (1927) are in Cooperstown. The streak ended in 1956 when Bill Rigney took the helm. A decent player for the Giants for 8 seasons, and a major league manager for 18 seasons, Rigney had a notable career but he was not Hall of Fame material.

Ott, of course, did not make it to Cooperstown on the strength of his managerial record (464-530). His career as a player, more specifically his offensive prowess, was what propelled him to the Hall of Fame, and that 18-year home run streak was a unique feature of his legacy (it is not listed on his plaque in Cooperstown, however).

Now I don’t want to go out on a limb and say Ott’s streak will never be equaled or surpassed. Maybe some young slugger is in the early stages of doing so as you read this. Pete Alonso, for example, has led the Mets in homers in each of his first three years (2019-2021), so maybe 15 years from now he will tie Ott.

He did not start as early as Ott (he was 24 in his rookie year) so he will have to stick around till age 41to do so. Check with Las Vegas for odds on this happening. It doesn’t hurt to place a minimum bet on a long shot now and then, but you also have to consider the odds that you’ll live long enough to collect your winnings in 2036.

I think it’s safe to predict you’ll see Y-A-S-T-R-Z-E-M-S-K-I as the answer in a crossword puzzle long before another major leaguer leads his team in home runs for 18 consecutive seasons.

The Giants; Memories and Memorabilia From a Century of Baseball , by Bruce Chadwick and David M. Spindel, Abbeville Press (New York, 1993)

Hall of Fame Players, Cooperstown by Bruce Herman, Publications International, Ltd. (Lincolnwood, IL, 2007)

The New York Giants; an Informal History of a Great Baseball Club , by Frank Graham, Southwest Illinois University Press (Carbondale, 1952)

The SABR Baseball List and Record Book , ed. Lyle Spatz, Scribner (New York, 2007)

The World Series, An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Fall Classic , by Josh Leventhal, Tess Press (New York, 2004)

“Danny Gardella” by Charlie Weatherby, SABR Biography Project, sabr.org

“Harry Danning,” by Warren Corbett, SABR Biography Project, sabr.org

“Mel Ott,” by Fred Stein, SABR Biography Project, sabr.org

“Phil Weintraub,” by Ralph Berger, SABR Biography Project, sabr.org

1933 – The Giants lose 3B Johnny Vergez for the season due to an appendectomy. Travis Jackson, who has been filling in at SS, shifts to 3B,” thisdayinbaseball.com

The Sporting News Conlon Collection (baseball card set), Mel Ott, #225, #1254

baseballalmanc.com

baseballreference.com

crescentcitysports.com/leo-durocher-to-mel-ott-nice-guys-finish-last/

mlb.com/giants/history/season-records

wikipedia.com