First Dibs . . . Second Thoughts?

August 7, 2022 by Frank Jackson · Leave a Comment

First-round draft picks always attract attention. There are 30 of them in the amateur draft every year, and the deck gets reshuffled annually. Great expectations abound, and being a first-round draft pick can be a burden.

First-round draft picks always attract attention. There are 30 of them in the amateur draft every year, and the deck gets reshuffled annually. Great expectations abound, and being a first-round draft pick can be a burden.

The same is true of expansion drafts. Every expansion team gets a first-round pick who attracts a lot of attention because he becomes the first player on the roster in the team’s history. The difference is that this first-round pick is also a castoff.

Each existing team gets to protect a certain number of players on its roster and the rest are subject to the expansion draft. For the first-round pick, the bad news is your current team doesn’t want you; the good news is the new team really wants you. Unlike the amateur draft, the expansion draft offers a team a choice between a veteran and a prospect.

Since 1960 MLB has added 14 teams. Fourteen is a manageable number, so we can easily examine each first-round pick and see how he worked out. So let’s set the Way-Back machine for 1960 and the first-ever expansion draft picks.

The first expansion draft took place on December 14, 1960, and the Los Angeles Angels got first pick, while the Washington Senators (replacing the erstwhile Senators who had moved to Minnesota) got the second pick. Rules dictated that each existing American League club had to offer 15 players from the 40-man roster, including 7 from the active roster. The Angels and Senators could draft a maximum of seven players from each club. They had to take at least 10 pitchers, 2 catchers, 6 infielders, and 4 outfielders.

The first players taken were from the Yankees, which is not surprising, given the franchise’s talent level at the time. Pitcher Eli Grba was the first player ever selected in an expansion draft, while teammate Bobby Shantz was right behind him. In fact, in the next round, the Angels selected Duke Maas of the Yankees, so the Bombers had to cough up the first three players. All the picks in the first ten rounds were pitchers.

In 1960 Grba was 6-4 with a 3.68 ERA as a starter and reliever (80.2 innings in 24 games). Not a bad showing but Grba was hardly a mainstay of the Yankee dynasty. He went down in baseball history, however, as the only MLB player with G-R-B as the first three letters in his last name.

For the Angels, however, Grba was good enough to start the first game in franchise history on April 11, 1961 at Baltimore. He produced the first victory in franchise history, a 7-2 complete game. Grba went 11-13 for the season, tied with Ted Bowsfield for second on the team in victories behind staff leader Ken McBride with 12.

It was a perfectly respectable performance, and at age 26, Grba should have had a number of productive years left. Unfortunately, he had a drinking problem, so his MLB career was over two years later. Final totals: 28-33, 4.48. The Angels likely expected better. If draft picks came with do-overs, the Angels probably would have done a do-over.

The Senators tried a different strategy, choosing veteran Shantz. The diminutive (5’6”, 139 pounds) southpaw had enjoyed an unusual career, peaking at age 27 with the Philadelphia A’s in 1952, when he led the league in victories and winning percentage (.774 based on 24-7) in 279.2 innings.

Over the years, Shantz started fewer and fewer games and came out of the bullpen more and more. In 1960 with the Yankees, he was an effective reliever (5-4, 2.79 ERA in 42 games in 1960), but he turned 35 years old at the end of the season. What would the Senators want with someone like Shantz?

As it turned out, the Senators didn’t want him, but the Pirates did. Two days after the draft, the Senators flipped him to the Pirates (whom he had faced in three games during the 1960 World Series) for Harry Bright, Bennie Daniels, and R.C. Stevens. Bright and Stevens were of little consequence, but Daniels led the Senators in victories (12) during the franchise’s first season. Given the timing, one wonders if the Pirates and Senators had some sort of pre-draft gentleman’s agreement.

Shantz, by the way, performed for the Pirates pretty much as he had for the Yankees. In 1961 he went 6-3 with a 3.32 ERA in 43 games. But the Bucs had slipped from World Series champs to a 75-79 record and a 6 th place finish, so roster turnover was a given. As a result, Shantz was left unprotected in the 1961 National League expansion draft and was selected for the second consecutive year when Houston picked him in the 21 st round.

He was only with the Colt .45s till May 7, 1962, when he was traded to the Cardinals. He must have felt unwanted, yet he continued to pitch till age 39. Shantz spent the final six weeks of the 1964 season as a member of the Phillies during their historic meltdown. Retirement probably looked like a pretty good option at that point.

Shantz was not the only veteran the Colts chose in the expansion draft. Their first pick was a utility infielder, the Giants’ Eddie Bressoud (29 years old, six years experience). Whether Houston was interested in him as a potential player or potential trade bait is hard to say, but he never played a day for the Colts, who traded him to the Red Sox for error-prone shortstop Don Buddin six weeks after the draft.

Buddin did not appear to be an upgrade over Bressoud, and indeed he hit a mere .163 in 80 at bats before being sold to Detroit, where he simultaneously finished the 1962 season and his MLB career. He spent 1963 through 1965 in the minors and retired at age 31. Bressoud, meanwhile, played four more seasons for the Red Sox, followed by one with the Mets and one with the Cardinals. Just why the Colts wanted Buddin (he was only two years younger than Bressoud) remains a mystery. Bressoud was not a bad choice, but the Colts did not reap any benefits from him.

Meanwhile, the Mets selected another Giant, namely catcher Hobie Landrith. When asked why the Mets chose Landrith, manager Casey Stengel noted that without a catcher, the team would have a lot of passed balls. Casey was joking, but he made a point in his typically left-handed sort of way. Landrith was a veteran (he emerged in MLB in 1950 with the Reds) backup catcher, so at least the Mets would not be embarrassed with him behind the plate.

Landrith didn’t have much opportunity to embarrass the Mets or himself, as he was sent to Baltimore – as the proverbial player to be named later – on June 7 after a mere 45 at bats. Nevertheless, Landrith’s place in Mets history is secure because he turned out to be the player they gave up to acquire the legendary Marv Throneberry. As a side benefit, Landrith’s absence opened up more at bats for catcher Choo-Choo Coleman, yet another name to conjure with in Mets history.

By the time the next round of expansion rolled around, the four teams from the first round of expansion had shown little progress. The Mets remained doormats and the Colts/Astros had never won more than 72 games in a season, though they did have the Astrodome to add some distinction to the franchise. The Senators had never finished higher than 6 th out of 10.

The Angels had been the most successful franchise, finishing 5 th twice and 3 rd once. So that’s one first division finish for four teams during that entire span. Hardly a ringing endorsement of the four teams’ draft picks, first-round or later.

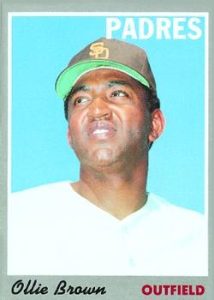

After the 1968 season, the San Diego Padres had the honor of the first pick in the next draft. They chose outfielder “Downtown” Ollie Brown from the Giants. Given his nickname, power hitting was expected of him, but he had not particularly distinguished himself with the Giants from 1965 to 1968. With the Padres in their first year, he hit 20 home runs with 61 RBIs and a .264 BA, eminently respectable stats in those days. The following year, he improved to 23 HR, 89 RBIs and .292, forming one third of a pretty decent heart of the order along with Nate Colbert and Clarence (Cito) Gaston.

After that, his stats went down, his playing time went down, and he became a part-timer with the A’s, Brewers, Astros, and Phillies. So Brown had an immediate impact on the Padres and a respectable major league career; in short, not a bad choice, given the available options – and certainly better than the four first-round picks from the previous expansions.

The Montreal Expos also made a good pick but botched it. They chose Manny Mota from the Pirates. At the time, it probably seemed of little consequence, but in retrospect, the ramifications were large. Though Mota was a veteran, he had more years ahead of him than behind him.

Arriving in the majors with the Giants in 1962, Mota was traded to the Colts after the season but never played for them during the regular season, as he was shuffled off to the Pirates before opening day of 1963. With the Bucs from 1963 through 1968, he was a solid part-timer, both at the plate and in the field, where he played all three outfield positions, and on occasion second base, third base, and catcher. But he was 30 years old and the Pirates felt he wasn’t worth protecting. Little did they know.

Despite the fact that Mota got off to a good start with Montreal (.315 on 28 for 89), the Expos traded him (and Maury Wills) to the Dodgers, where his skill as a contact hitter made him a pinch-hitting legend. When he retired with 150 pinch hits, he was the all-time MLB leader (his total has since been surpassed by Mark Sweeney with 175 and Lenny Harris with 212).

And what did the Expos get in exchange for Mota? 31-year-old Ron Fairly and Paul Popovich. The former came through with several decent seasons for the Expos, but Popovich was immediately peddled to the Cubs, for whom he had made his first MLB appearance in 1964.

So it was a good decision to pick the veteran Mota in the expansion draft, and a bad decision to let him go, as he had 12 more seasons of baseball left in him. The Expos could not have foreseen such longevity, yet one wonders how often Gene Mauch (Expos’ manager from their inception through 1975) scanned his bench in search of a pinch-hitter and thought, “Gee, I sure wish Manny was here.”

In the American League 1968 expansion draft, the Seattle Pilots selected Don Mincher from the Angels as their first pick. For better or worse, he was with the Pilots from opening day to the bitter end. Having hit 130 home runs in 9 seasons, mostly with the Twins, he hit a team-leading 25 homers and drove home 78 (2 behind team leader Tommy Davis) while hitting .246 for the Pilots. Not bad at all – in fact, it was good enough to attract the attention of the Oakland Athletics, who traded for him in the off-season before the Pilots gave up the ghost and moved to Milwaukee.

The A’s were probably satisfied as they got pretty much a carbon copy season from Mincher: same batting average; 2 more homers but 4 fewer RBIs. He was pretty close to the end of his career, however, as he retired after the 1972 season, which allowed him to bow out with a World Series appearance and an even 200 home runs.

The Seattle Pilots made a lot of bad decisions in their one year of existence, but choosing Mincher was not one of them. He went into the books as the first All-Star in the franchise after he replaced teammate Mike Hegan, who had to bow out due to injury. The long-term consequences to the franchise were negligible, but given the Pilots’ one-year tenure, long-term thinking was a moot point.

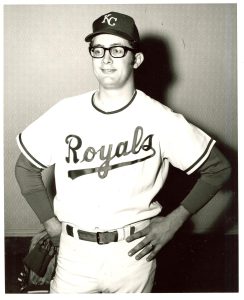

The Kansas City Royals went another route in the 1968 expansion draft. They chose pitcher Roger Nelson of the Orioles, which probably evoked a response of “Who?” Indeed, his MLB footprint had been small but promising.

Arriving in the big leagues with the White Sox in 1967, Nelson appeared in just 5 games but chalked up a 1.29 ERA. After the season he was shipped off to the Orioles in a trade that brought Luis Aparicio back to the White Sox. Starting the season at Triple-A, he was brought up by the Orioles and did nothing to disgrace himself, going 4-3 with a 2.41 ERA in 19 games.

1968 was popularly known as the Year of the Pitcher, and the pitching-rich Orioles (staff ERA of 2.66) couldn’t keep everybody. So Nelson took his act to the starting rotation of the newborn Royals. The result was a 7-13 record and a 3.31 ERA in 193.1 innings, acceptable stats for a pitcher in his first full season with a team in its first season. Curiously, he placed no higher than 5 th place on the staff in victories. Wally Bunker (25 th pick in the draft), his former teammate with the Orioles, led the staff with 12, while Moe Drabowsky (pick No. 42), yet another former Oriole, won 11.

Nelson’s next two seasons were forgettable, but he rebounded with a record of 11-6 and a 2.08 ERA in 1972. His finest hour came on October 4, 1972, when he pitched a two-hit shutout (4-0 versus the Rangers) in the last game ever played at Municipal Stadium in Kansas City.

In the off-season Nelson was traded to Cincinnati, where he was used sparingly (14 games each in 1973 and 1974) with so-so results. The grand totals for his career were 29-32 and 3.06. Nevertheless the trade was notable because it brought Hal McRae to Kansas City, where he enjoyed a 15-year career. So in a sense, the Nelson pick paid big dividends for the Royals.

In the 1976 draft, both new teams (Mariners and Blue Jays) followed the same strategy. Both went with youth and both chose wisely, as both choices were named to the Topps All-Rookie team. This draft marked a turning point, as from this point on, expansion teams were more interested in promising young players than veterans.

The Mariners’ choice was highlighted by Danny Kaye (part-owner of the team) making the first selection. He chose the Royals’ Ruppert Jones, a 21-year-old center fielder. Obviously, the Mariners were thinking long-term and not seeking instant credibility. Jones had moved up through the minors in the Royals’ system and surfaced with them for 51 at bats in 1976. The bulk of his season was at Triple-A Omaha, where he hit 19 homers, drove home 73, and hit .262. He was ready for the big time, but there was nowhere for him to go with the Royals, who had just won their first AL West title.

Amos Otis was in his prime and ensconced in center field, and they had Willie Wilson waiting in the wings. So Jones was expendable. The choice was a boon for the Mariners, as Jones quickly became the face of the infant franchise, playing in 160 games, and going down in history as the team’s first-ever All-Star. He more or less replicated his Triple-A stats from the previous year, as he hit .263 with 24 homers and 76 RBIs.

The fledgling Blue Jays chose the versatile 25-year-old Bob Bailor from the Orioles. The O’s were a dominant team in the mid-70s and there was no room for Bailor. He had done well at every stop along the way, but his experience with the big league club was limited to a few at bats in 1975 and 1976.

In his rookie year with the Blue Jays, Bailor hit .310 playing mostly in the outfield (47 games in center field, 15 in left, and 2 games in right) but also at shortstop (53 games) and 7 games at DH. As it turned out, that was his best offensive season. The rest of his career with the Blue Jays, as well as the Mets and Dodgers, was decent, resulting in 775 hits and a .264 batting average.

He continued to play all over the field. Aside from first base and catching, he played every other position (he pitched for the Jays in three games in 1980). After his playing days were over, he returned to the Blue Jays as a minor league manager and first base coach.

In 1992, the expansion teams were not limited to players in their own leagues. They could choose from any MLB team, so the talent pool was much greater. Nevertheless, the Colorado Rockies remained in the NL for their first pick, choosing David Nied from the Atlanta Braves.

Having won their second straight NL East title, the Braves were in the early stages of an extraordinary streak when they ran the table in their division every year, save the strike year of 1994, through 2005. In 1992 Steve Avery, Tom Glavine, and John Smoltz, played a big part in the Braves’ emergence, but not all the young arms could be protected, so Nied was the odd man out.

A product of the renowned baseball program at Duncanville (TX) High School, Nied had worked his way up the minor league system, going a combined 15-6 in 1991 at two levels (High-A and Double-A), and 14-9 at Triple-A Richmond in 1992, topping it off by going 3-0 with a 1.17 ERA with the Braves at the end of the season. He positively radiated potential, and the Rockies got the message.

Starting the first game in Rockies’ history, on April 5, 1993, a 3-0 loss to the Mets at Shea Stadium. Nied got what would now be known as a quality start, giving up two earned runs in five innings, but he was matched against Dwight Gooden, who pitched a four-hit shutout. Nied also got the first complete game victory for the Rockies on April 15, a 5-3 victory over the Mets at Mile High Stadium in a rematch with Dwight Gooden in front of 52,608, only 519 fewer than had witnessed the opening day match in New York.

On June 21, 1994, Nied notched the first complete-game shutout in franchise history, an 8-0 whitewashing of the Astros in front of 56,913 at Mile High Stadium. At that point, his record for the season stood at 6-4. Incredibly, he would garner just three more victories that season and none during the next two seasons. By age 27, when he should have been in his prime, he had pitched his last big league game. So the Rockies’ choice initially appeared to be a good one but it went south on them. There are no guarantees.

Meanwhile, the new NL East franchise, the Florida Marlins, chose Nigel Wilson of the Blue Jays. One can imagine that Wilson, who had grown up in Ontario, was likely disappointed to be exiled from his hometown team. The Marlins’ pick was a calculated risk. True, in 1992 Wilson had clubbed 26 homers at Knoxville in the Southern League, but that was Double-A ball. Promising to be sure, but worthy of a team’s first pick in the expansion draft?

As it turned out, the Marlins wasted their pick. Wilson did well enough at Triple-A Edmonton, hitting .292 with 17 homers and 68 RBIs, but after he was promoted to the Marlins at the end of the 1993 season, he flopped. He came to bat 16 times with no hits and 11 strikeouts. Obviously, some more seasoning was necessary. He spent all of 1994 at Edmonton, batting .309 with 12 homers and 62 RBIS, but he never played another game with the Marlins, who put him on waivers. Again, he did well at Triple-A, this time at Indianapolis, the Reds’ affiliate, where he hit .313 with 17 home runs and 51 RBIs in 304 at bats.

Wilson was promoted to the Reds at the end of the 1995 season but still did not get his first MLB hit. He struck out 4 times in 7 at bats. The Indians took a flyer on him and assigned him to Triple-A Buffalo. Again he did well (30 HR, 95 RBIs, .299) and was promoted to MLB at the end of the season. He finally got his first MLB hits (in fact, two of his three hits were home runs), and even got one plate appearance in the ALDS against Baltimore, but that was it for his MLB experience.

Released by the Indians, he said sayonara to Cleveland and joined the Nippon Ham Fighters in 1997; coincidentally, this was the year the Marlins won their first World Series title. Wilson had some notable seasons with the Fighters, but that was no consolation to the Blue Jays.

So that brings us to the last expansion draft 19 years ago. This time around each league added one team (the Diamondbacks in the NL, the Devil Rays in the AL) with the Milwaukee Brewers moving from the AL to the NL to keep an even number of teams in each league. Both expansion teams went for young pitchers.

The Devil Rays reached across the state and selected Tony Saunders from the Marlins. Saunders had a decent enough record in the minors but he had only one outstanding season. In 1996 he went 13-4 with a 2.63 ERA for the Portland Sea Dogs of the Double-A Eastern League. In 1997 he was 4-6 with a 4.61 ERA in 22 games with the Marlins. He might have been worth a draft pick somewhere down the line – but number one?

In the Devil Rays’ first season, he went 6-15 with a 4.12 ERA. He did, however, eat some innings (192.1 innings), so perhaps he had a future of some sort. Unfortunately, 1998 proved to be his career year. Going back and forth from the minors to Tampa Bay in 1999, his MLB log that season was 3-3 with a 6.43 ERA in 42 innings. And that was it for his MLB career. At age 25, his career was all but over. Thanks to injuries, he sat out 2001 through 2004. At age 31, he surfaced as a closer with the Mesa Miners of the independent Golden League. He pitched 10 innings in 9 games and that was the end of his career.

The Diamondbacks chose Brian Anderson from the Indians. It was a bit of a head-scratcher. Like Saunders, he might have been worth a draft pick down the line – but number one?

Anderson got his feet wet in MLB at age 21, appearing in four games with the Angels in 1993. Over the next two seasons he went 13-13 with the Haloes, pitching a little over 200 innings total but with an ERA well over 5.00. His next two seasons with the Indians were a little better. In two seasons he was 7-3. His ERA dipped below 5.00 but he only pitched about half as many innings. There was nothing special about Anderson, but he was a left-hander, and according to conventional wisdom, lefties develop later than righties. The Diamondbacks must have figured he would mature on their watch.

Actually, they weren’t far wrong. Anderson gave the Diamondbacks five workmanlike seasons. His ERA was still nothing to write home about, but he went 41-42 in 840.2 innings. Returning to the Indians at age 31 as a free agent in 2003, he gave them 148 innings and posted a 9-10 record with his career-best ERA of 3.71. He was traded to the Royals in August and posted a 5-1 record the remainder of the season. His composite record of 14-11 and 3.78 in 197.2 IP was his career year.

Unfortunately, he followed this up in 2004 with his worst season (6-12, 5.64). After 6 games with the Royals in 2005 he was released. He later signed with the Rangers but never played with them. He finished up with 13 years of MLB service, a record of 82-83, and a 4.74 ERA.

It shouldn’t be surprising that the results of previous first-round expansion picks show mixed results. But it seems as though the chances of securing high-caliber, long-term help are slim. The word is out that selecting veterans is no way to kick-start a team. Selecting younger players makes more sense – but which ones? The original teams are not going to make their top prospects available. You can never have too much pitching, but young pitchers often get injured or just plain underachieve.

Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred has been making noises about another round of MLB expansion as soon as Oakland and Tampa Bay resolve their stadium problems. So there is a good chance we’ll get to see another expansion draft a few years from now.

Given the increasing sophistication of statistics, there’s no doubt that future expansion teams will have a lot more data at their fingertips than their predecessors had. Will that enable them to make better decisions? Sooner or later, no matter how much or how little data you possess, you have to make a hard choice. If you’re the GM of an expansion team, you have to ask yourself one question: “Do I feel lucky?”

Well, do you, punk?