Users, Cheaters, Six-Time Losers, and the Search for Dignity

June 25, 2023 by Jeff Cochran · Leave a Comment

( Author’s Note:This story is the sequel to “Hank Aaron and Bob Dylan: Searchin’ High, Searchin’ Low For Dignity,” posted 4/16/23)

In the spring of 2005, Atlanta’s Center for Puppetry Arts held a fundraiser in a posh Buckhead home, not far from the Georgia Governor’s Mansion. Since the Center for Puppetry Arts was an advertising account of mine at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution , I was invited to the soiree. Yes, it would be great sipping a beer while checking out the beautiful old home on a grand slice of Atlanta real estate, but the evening’s highlight was an appearance by Henry and Billye Aaron. The Aarons had taken a special interest in the Center for Puppetry Arts, promoting the great work of founder Vincent Anthony, who welcomed Kermit the Frog and his creator, Jim Henson, as they cut the center’s opening day ribbon on September 23, 1978.

Appropriately enough for an event featuring Aaron, the fundraiser was low-key. A gentleman speaking on behalf of the Center for Puppetry Arts extolled the attraction’s great works and its future plans. Then the Aarons were introduced. And so was — in a casual way — the matter of Aaron’s Major League Baseball home run record being challenged by San Francisco Giants outfielder Barry Bonds, long suspected of using steroids to enhance his physique and hitting performance.

Bonds’ less-than-legitimate baseball accomplishments were mentioned, along with the opinion that if Bonds passed Aaron’s home run total of 755, it wouldn’t matter. The real Home Run King was there in the room with us. Aaron smiled and shook his head. He didn’t want to talk about it. Not there. Not then. Not at all.

Getting entangled in that topic was the last thing Aaron had in mind. In The Last Hero, Aaron biographer Howard Bryant wrote that “ Henry was personally and permanently offended by Barry Bonds.” Still, he kept his thoughts on Bonds mostly to himself. Bonds was, in Aaron’s words, a “lose-lose.” If he publicly raised the issue of Bonds and steroids, Aaron, according to Bryant, risked “criticism that he was just a bitter old man who could not deal with his record being broken.”

That wasn’t the attitude Aaron wished to convey, yet he also realized if he “supported Bonds in his quest to break the record, he would be tacitly condoning steroids and performance-enhancing drugs,” and for Aaron, that went against the grain even more. As Bryant sums it up, Aaron “didn’t want to be associated with the drug culture, which had changed the game and the way the sport was viewed.” Yes, for Aaron, talking about Bonds was a “lose-lose.”

Still, the world of Baseball, as in those on the inside, plus those watching from the stands or at home, realized Aaron’s achievements were hard-earned and genuine. Aaron’s character and reputation had preceded this matter. As his former teammate Ralph Garr told Bryant, “The one thing Henry hated was cheating. The whole thing bothered him.”

The same couldn’t be said of Bonds, Mark McGwire, Alex Rodriguez, Sammy Sosa, Rafael Palmiero, and other contemporaries whose home run numbers far surpassed those of sluggers going back to the 1920s. They were cheating, soiling the dignity of Baseball and the players who followed the rules over the previous 100-plus years. Aaron knew the drug-driven sluggers had dishonored the game and diminished the legitimate feats of players.

Also complicating matters was that one of Aaron’s best friends since the 1950s was Bud Selig, the Commissioner of Baseball. Selig had been in the commissioner’s chair* since 1992, guiding baseball through years of turmoil, triumph, and many changes, some welcome, some not. A diplomatic fixer, Selig was perfect for the job. His gateway to Major League Baseball (MLB) was his family’s Ford dealership in Milwaukee. He sold cars to members of the Milwaukee Braves like Aaron and Joe Torre. Soon he started attending Green Bay Packers games with Aaron.

Selig bought stock in the Braves, becoming the team’s biggest investor, but he had no say in keeping the Braves from moving to Atlanta in 1966. Afterwards, he began seeking another team to play in Milwaukee, nearly finalizing a deal to buy the Chicago White Sox in 1968. When that fell through, he bought the Seattle Pilots, an expansion team that had only played one miserable season. In 1970 the Pilots became the Milwaukee Brewers. Selig’s perseverance was admirable. Someone else could sell the cars, he’d run the Brewers and make sure his town kept them.

Selig soon learned that hustling to secure a new team for Milwaukee proved far easier than serving as chief executive for organized baseball in an avaricious, too-often drug-enticed culture. During most of Selig’s years as commissioner, MLB was prosperous, at a financial zenith, but possessing an ugly truth: The powers-that-be were hesitant to blow the whistle on cheating. So were the players, who balked at drug-testing for performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs).

Bigger muscles made for more home runs, which made for bigger crowds and more money for the game, which of course, meant more money for the players. The players, after all, were the main attraction, and if the turnstiles kept humming, team owners gave PEDs less thought than merited. Cheating was not only being ignored and winked at, it was, for all intents, celebrated throughout the national media. The cover story in the October 5, 1998 issue of Sports Illustrated proclaimed “that in 1998 baseball enjoyed… The Greatest Season Ever,” due in great part to the home run race of Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa as they both topped Roger Maris’ single-season home run record.

In his 2019 memoir, For The Good Of The Game, Selig acknowledges Baseball had a doping problem going back to the late ‘80s. In ‘88, Washington Post sports columnist Thomas Boswell told Charlie Rose on a CBS program that Oakland Athletics superstar Jose Canseco was “the most conspicuous example of a player who has made himself great with steroids.” Canseco vehemently denied it, but fessed up in his first memoir, Juiced, published in 2005.

The memoir produced some wild claims, including that “85% of major league players took steroids.” Then came the graphic revelation that he and Mark McGwire would shoot up together in the toilet stalls of the Oakland Athletics’ clubhouse. McGwire immediately denied Canseco’s story, but in 2010, admitted he had used steroids off and on for a decade, including “The Greatest Season Ever” of 1998.

Selig writes that in 1994, while drafting the new collective bargaining agreement, team owners proposed a provision for drug-testing. The players flatly rejected it and the owners decided not to go to war over PEDs. From there, the parties focused on the core issue, revenue structure — the one on which they remained poles apart, enough for labor talks to break down, causing a player walk-out. The ‘94 major league baseball season ended on August 11, leading to, for the first time in 90 years, the cancellation of the World Series.

This wasn’t good news for fans, among them Bob Dylan, whose interest in the game was made evident in his 1975 song about pitcher Catfish Hunter (“Catfish”) and a baseball episode on his Theme Time Radio Hour ( first aired May 24, 2006) . Baseball teams have road trips and Dylan has the Never Ending Tour, a handle for his seemingly endless performance schedule that began in June ‘88.

In the fall of ‘94, Dylan was hitting a few big-league cities, but mostly minor league towns, and even smaller burgs like Gainesville, Georgia — the “poultry capitol of the world.” The intense concert schedule lit a fire in Dylan. That fiery spirit was especially manifested in his concert that summer at Woodstock ‘94. Still, he wasn’t creating new material at anywhere near the pace he set in previous decades. Only one album of new Dylan original compositions had been released in the first seven years of the ‘90s ( Under the Red Sky in September ‘90).

The songs did not come as fast as they did before, Dylan acknowledged to Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times in ’92. Then on November 15, 1994, maybe 2-3 weeks after the World Series would have been decided, came a new Dylan song, “Dignity,” on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Volume 3. “Dignity” could have been included on Dylan’s ‘89 album, Oh Mercy, but he and producer Daniel Lanois were not satisfied with any of the umpteen versions they worked on at The Studio, New Orleans. So, the song was set aside for five years.

For the new collection of greatest hits, an original multi-track recording of “Dignity” from the Oh Mercy sessions was given to Brendan O’ Brien, an up-and-coming producer, for remixing. What O’Brien came up with was most unfortunate. In his Dylan opus, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia , Michael Gray appraises O’Brien’s work by saying, “All he did for “Dignity” was ruin it.”

Gray continued:

… the first thing Brendan did was abolish its stand-out rhythm. Then he put all these silly “modern” noises on. Then he pushed Dylan down in the mix so you hardly notice any piano at all and so that this long, immensely entertaining lyric, delivered with great panache by a Bob Dylan firing on something like all cylinders, is no longer accessible or ready to jump straight out of the radio at you but instead needs painful attending-to.

In the very same week his treatment of “Dignity” was released, O’Brien got another chance and made the most of it. On November 17 and 18, Dylan and his band, including O’Brien, appeared at the Sony Studios in New York to record an edition of the MTV Unplugged series. It was a terrific show. The Los Angeles Times called it “unforgettable” and “the concert of the year.” Standing out among many great selections was the presentation of “Dignity.” Dylan provides an engaging vocal while his band plays in a spirited fashion on the jaunty and swaying song.

O’Brien, at the Hammond organ, discovers his inner-Matthew Fisher,** playing riffs that embraced the charm of Dylan’s melody. In less than six months, a CD of the show would be released, allowing us to set aside the version of “Dignity” on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Volume 3, while in the years to come, at least three other versions of the song from the New Orleans sessions would be included in future Dylan compilations.***

Michael Gray calls “Dignity” a “great song, which describes so resourcefully the yearning for a more dignified world,” concluding that “the song is accessible to anyone who cares to listen, and offers a clear theme, beautifully explored, with which anyone can readily identify.”

Of course, anyone observing society and all it produces and all it consumes is easily disappointed at the turns culture takes. We can readily identify. We can also acknowledge that a baseball strike is hardly a major concern like that of climate change, the banning of books in community libraries, food insecurity, crime, and restrictive voting laws enacted in red states when their candidates fail to get elected. However, over 64 million people attended major league baseball games last year.

We’re talking baseball, not wrestling. Followers of the game expect a sense of fairness to be exhibited by the players, umpires, and those administering the sport. They also deplore interruptions in the season when players and owners cannot agree to a collective bargaining agreement, as was the case in 1994 when big league baseball was advancing to an all-time attendance record. If you go to an Atlanta Braves game at Truist Park this season and decide you want a Heineken, it will cost you as much as what a Heineken six-pack will cost you at the grocery store.

There’s a lot of money to be made and the lords of the game are going to make sure every cent of it comes rolling in. As Dylan said in “Blind Willie McTell,” “power and greed and corruptible seed seem to be all there is.” And in the environmental/economic order, as well as in our pastimes, societal vulnerabilities are made evident. Consider the first two lines of the verse from “Dignity,” just below. It’s what we live with.

Chilly wind sharp as a razor blade

House on fire, debts unpaid

Gonna stand at the window, gonna ask the maid

Have you seen dignity?

Baseball recovered from the ‘94 strike, although many devoted fans took their time returning to the ballparks or even watching the games on TV. The strike left a bitter taste. Walk into any sports bar and you’d find guys blaming the millionaire players for being such selfish bastards, while ignoring any fault of the billionaire owners, who are provided taxpayer dollars to build and maintain their stadiums. Many of the guys badmouthing the players in the sports bar were likely getting squeezed, at least indirectly, by billionaires.

It appears respect is more easily granted to the super-wealthy and powerful, such as the owners, even if they gain a part of their riches and power through various confiscations of the taxpayers’ hard-earned money. There is dignity in the labors of men and women, but the dignity goes neglected when tax dollars they’ve paid for critical community needs are used to increase the comfort levels of the wealthy.

Since the ‘94 strike, Major League Baseball has gained 19 new stadiums, most of them subsidized in part by taxpayers. The new stadiums, nearly all of them sparkling structures, are money-making machines with corporate suites and a wide array of concession items that easily separate fans from their money. Baseball’s building boom has given the game the glow of wealth. In his memoir, Bud Selig recognizes the unprecedented addition of new ballparks:

At least at the start of the building boom, new stadiums played a major role in revitalizing struggling franchises. They generated badly needed revenues, which went into player salaries and the building of teams, helping them either reach the playoffs or at least become more competitive. Then the success built on itself.

The tens of millions following the game were thrilled with the new ballparks, although even devoted fans had to be disgusted over tax dollars being used for the expensive playpens. But more than the iron and steel of the new ballparks, it was the new “Iron Man,” Cal Ripken of the Baltimore Orioles, who provided fans nationwide a cause for joy and appreciation.

On September 6, 1995, with fans still doing a slow burn over the previous year’s strike, Ripken played in his 2,031st consecutive game, breaking the record held since 1939 by Lou Gehrig, the New York Yankees Hall-of-Famer who retired after being stricken by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known since as Lou Gehrig’s disease. His consecutive games record was considered one of the few in MLB that wouldn’t be broken.

Gehrig, like Hank Aaron, was admired not only for his immense skill as a player, but also for his character. After game 2,030, he never played in a major league game again. He grew weaker and would die less than two years after his July 4, 1939 farewell speech in which he declared himself “the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

Central casting could not have picked a more appropriate player than Ripken to succeed Gehrig as MLB’s “Iron Man.” Not relying on steroids or Andro to break Gehrig’s record, Ripken would simply grab his glove and trot out to shortstop or third base every day from May 30, 1982 through September 20, 1998 for a career total of 2,632 consecutive games.

When he broke Gehrig’s record on that September evening of 1995, play was stopped as the game became official in the bottom of the fifth inning. For 22 minutes, the players, the umpires and the fans at Oriole Park at Camden Yards gave Ripken a standing ovation.

Then Ripken returned the favor by lapping the field’s entire warning track, reaching out to the people to the stands, shaking hands and giving high-fives. In one of the most-watched baseball games ever, fans tuning into ESPN shared in the event, where President Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore and Yankees great Joe DiMaggio, a teammate of Gehrig’s, gathered to pay tribute to Ripken.

Baseball had its warm and glorious moment. It was like the ‘40s when the game was truly the national pastime. A beloved player, who, by the end of his 21-season career, would collect 3,184 hits, 431 home runs, win the American League’s Most Valuable Player award twice and then be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2007 on the first ballot with 98.5 of the votes, was publicly celebrated as no player had ever been. As he lapped the warning track on that Baltimore night, Ripken was ecstatic, as happy as George Bailey in the last 5 minutes of It’s A Wonderful Life.

As he lapped the warning track on that Baltimore night, Ripken was ecstatic, as happy as George Bailey in the last 5 minutes of It’s A Wonderful Life.

Bud Selig, the team owners, and the players must have felt a joyous epiphany. America would truly love the game again. But first, those running the game — and the players — needed to get out of their own way. Just like the users, cheaters and six-time losers who hang around the theatres in Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” MLB had its own frauds to contend with. And the lords of the game would not contend so well against them. The “users, cheaters and six-time losers” were relentless.

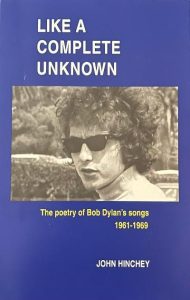

In Like A Complete Unknown, his book on the poetry of Bob Dylan’s songs from 1961 through 1969, John Hinchey illustrates what the “the artist” in “Subterranean Homesick Blues” faces.

“Subterranean Homesick Blues” is an exploding digest of an alternately gnomic and plain-spoken tips on eluding the traps society sets for our freedom.

Hinchey observes “the sense of menace and hidden malice” that pervades the song. The hostile society is enemy to Dylan’s “artist.” It’s pervasive, so don’t follow leaders and watch the parkin’ meters.

Nearly a quarter century passed between Dylan recording “Subterranean Homesick Blues” in 1964 and his first recordings of “Dignity” during the Oh Mercy sessions, but similar concerns are revealed in both songs. The “artist” in “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” as well as the wise man, the blind man, the drinkin’ man, the sick man, and the others searchin’ in “Dignity,” all face menace and hidden malice. They keep looking for dignity, lighting candles and trying to avoid the scandals.

The lords of Baseball, especially Bud Selig, — and the players — had it in their power to avoid scandals and maintain the game’s dignity. After all, MLB had a lot in its favor: New ballparks, an esteemed player like Cal Ripken surpassing the record of a beloved legend, and the fans, in just a few years after the strike, returning in record numbers, boosting the game financially. MLB was no longer, as Business Week reported in a 1985 cover story, a game in financial trouble.

Still, those running things couldn’t keep their eye on the ball. The users, cheaters and six-time losers of baseball were manipulating the game. Millions of fans went along for the ride, thrilled by the awesome power displays of McGwire, Sosa, Palmerio, Bonds, and others. The fans were deluded and they’d come to regret it.

Less than ten seasons after Ripken gave Baseball its ultimate PR moment, four manipulators — Bonds, Sosa, McGwire and Palmerio — entered the top ten of all-time home run leaders. Such individual-player achievements are usually cause for celebration. The news of a player’s 500th career home run makes the sports pages nationwide and the home run ball will likely be displayed in Cooperstown if it isn’t scooped up by someone doling out a six-figure check to the player.

MLB and its followers have always revered the game’s history, connecting the past to the present, but there was little celebrating when the manipulative players passed Lou Gehrig, Ted Williams, Ernie Banks, Mickey Mantle and Reggie Jackson on the home run list.

Bud Selig was running the game when the users, cheaters and six-time losers were tainting the record books with their drug-enhanced forgeries. A genuine baseball fan, this had to hurt Selig, especially since he was the commissioner. In his memoir, he admits to being caught off guard when McGwire and Sosa passed Maris in 1998. That’s when Barry Bonds, a far better player than either McGwire and Sosa, may have been caught off guard as well.

He wanted to feel some of the love they were receiving. He suspected McGwire had been juicing up. That’s when Bonds is believed to have started juicing as well. More players fell in line with the new regimen and the credibility of the game declined. It wasn’t until 2003 that players were tested for PEDs. That was a great step forward but too little too late. The assault on the record books was underway.

In the opening pages of his memoir, Selig conveys the sense of loss he felt in 2007 as Bonds approached home run 756. He tried to make sense of it but that proved impossible, noting, “It was the way Barry had piled up homers in the second half of his career, at a rate that seemed impossible to Henry and players from baseball’s other generations.” By 2007, Selig says, “We knew what was going on. This was an age when sluggers found extra power through chemistry, and, of course, Barry was one of the leading men in baseball’s steroid narrative.

“There is plenty of blame to spread around in this sad chapter, and I’ll accept my share of the responsibility. We didn’t get the genie back in the bottle in time to protect Aaron’s legacy.”

Never did any hard feelings pass between Aaron and Selig. Aaron knew the commissioner was in a tight spot. Their friendship remained strong after having done much to help each other over the decades. At the end of the ‘74 baseball season, not even six months after Aaron became the all-time home run king, he realized he would not retire from the game as planned. Aaron assumed he’d be given a key job in the Atlanta Braves’ front office, but that didn’t happen.

Thus, Aaron’s favored option was to play baseball for at least another year. But where? At the time, Braves management thought they’d do quite well in the years ahead without Aaron. (They learned otherwise — and how.) Bud Selig, still running the Milwaukee Brewers, sensed a great opportunity. He completed a trade with the Braves, returning Aaron to the town where he began his major league career.

Aaron played with the Brewers in ‘75 and ‘76, then in his early ‘40s, with a bum knee, no longer performing at the level of the previous two decades. Still, Selig believed the acquisition of Aaron was one of his most important moves during the years he owned the Brewers. He said Aaron “made a significant impact on one of our great young players, Robin Yount,” then only in his teens, but honing skills that would lead him to a first-ballot induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame after a brilliant 20-year career, each season in Milwaukee. Selig, in the eulogy he gave at Aaron’s memorial service two years ago, said Aaron was “a great and wonderful human being” who “had a special relationship with our fans.”

Beginning in the mid ‘80s, Atlanta Journal-Constitution sports columnist Terence Moore developed a close relationship with Aaron. Moore not only had the home run king as the ultimate source, but also a cherished friend. Moore writes about the depth of feeling Aaron had for baseball and life itself in The Real Hank Aaron, published last year.

The book is mostly a Hank Aaron biography, but partly a Terence Moore memoir. Over the decades Aaron shared his feelings with the sports columnist, who, as a Black man, navigated newsrooms when big media was starting to move beyond token integration. Certainly Aaron and Moore had to shake their heads in disbelief as they shared stories of slights and misunderstandings two decades deep into the 21st century.

Moore has a great recollection near the end of his book. On August 7, 2007, Barry Bonds lifted home run 756 in San Francisco. A few days later, Aaron and Moore discussed Bonds’ big moment. Aaron not only declined the opportunity to be at the San Francisco park when Bonds passed him numerically, he didn’t even see it live on TV, in the comfort of his own home. The real home run king was sleeping soundly in southwest Atlanta.

“It was 1:00 in the morning,” Aaron explained, “It wasn’t being disrespectful or anything. It’s just a matter of, hey, the body needed to go to sleep.” It was also a matter of a man being at peace with himself, possessing dignity.

So many roads, so much at stake

So many dead ends, I’m at the edge of the lake

Sometimes I wonder what it’s gonna take

To find dignity

Dylan said “Dignity never been photographed.” A valid point, for sure. But there are memories that lead to pictures in your mind. Mental photographs: they’re in your head, but just as real as any glossy photo held up for all to see. On that spring evening at the soirée in Buckhead, I took a mental photograph of Henry Aaron, smiling, but sad over the direction of the game he had enriched with dignity. Still, he must have taken the long view about any cheaters passing him on the all-time lists. They’d be found out soon enough — and they were. Those players are persona non grata in Cooperstown, New York, home of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Hopefully, the writers who vote on Hall of Fame membership will continue to draw a line against the cheaters who tarnished baseball. If they ever need a reminder, they can look at a video of the 2014 Hall of Fame ceremonies. Next to Joe Torre, a man of great integrity finally voted in, was his old teammate and friend, Henry Aaron. On July 27, 2014, you could have been “searchin’ high, searchin’ low, searchin’ everywhere…” but found dignity on the platform in Cooperstown.

*Bud Selig became acting Commissioner in 1992 and served as the 9th Commissioner of Baseball from July 9, 1998 through January 25, 2015.

**Matthew Fisher, the organist for Procol Harum on “ Whiter Shade of Pale.”

***Two recordings of “Dignity” were included on Tell Tale Signs, Rare and Unreleased 1989-2006, The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8, released October 6, 2008. Another is included on Sidetracks, a bonus disc on Bob Dylan: The Complete Album Collection, Vol. One, released on November 4, 2013.