A Star is Reborn: Satchel Paige in the Movies

September 19, 2023 by Frank Jackson · Leave a Comment

You might be surprised to discover that Satchel Paige

is included in the Internet Movie Database

, the encyclopedic go-to source for film buffs. In fact, he has four credits, three onscreen and one behind the screen.

You might be surprised to discover that Satchel Paige

is included in the Internet Movie Database

, the encyclopedic go-to source for film buffs. In fact, he has four credits, three onscreen and one behind the screen.

The first is a formality, as the credit is for an unscripted TV role in the 1948 World Series, which was widely, though not nationally telecast. All the participants on the Boston Braves and Cleveland Indians got a screen credit. A number of familiar names ( e.g ., Warren Spahn, Bob Feller, Johnny Sain, Lou Boudreau) are listed as well as some that have faded into obscurity. Paige got screen credit for making a relief appearance in Game 5.

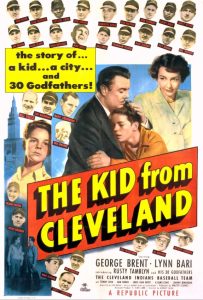

Paige’s second credit is for a 1949 movie called The Kid from Cleveland . As the film describes itself, “This is the story of a city, a kid and a baseball team.” In other words, prepare to have your heart warmed.

Right off the bat, this is a bad film, laughably so in some scenes. The kid, Johnny Barrows, is played by Russ Tamblyn, who was 14 when the film was released on Labor Day weekend of 1949. This was his first of many screen credits. You may not know his name, but if you’ve seen Samson and Delilah, Gun Crazy, Father of the Bride, Seven Brides for Seven Brides, Peyton Place, High School Confidential, and West Side Story , among many others, you have seen Russ Tamblyn. Taking on juvenile roles long after he attained majority, he eventually made the transition to more mature roles and continued to work through 2018.

Sad to say, Johnny Barrows is a budding juvenile delinquent (JDs, of course, would soon be all the rage in 50’s movies). His dad was killed in the war, and he can’t get along with his stepfather. Also, he’s become pals with another kid who is the proverbial bad influence. But he’s a big Indians fan and after he meets Super Chief Bill Veeck and the Tribe, they help him get his head on straight.

The cornball narrative aside, The Kid from Cleveland contains much of interest for Seamheads. For one thing, it includes game footage of the 1948 Indians taking on opponents during the regular season and the World Series. This was arguably the peak of the franchise when even the nosebleed seats at Municipal Stadium were in demand. Former MLB player/manager Lew Fonseca was in charge of directing and editing World Series highlight films at the time and has a screen credit for “Baseball Supervision.” n 1948 he provided “special baseball assistance” on The Babe Ruth Story , which makes The Kid from Cleveland look like Citizen Kane .

In addition to appearing in game footage, Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium is a recurring location for many non-game dramatic scenes in the movie. Also, League Park, the Indians’ bandbox alternative ballpark through 1946, stands in for Hi Corbett Field, the Indians’ spring training park in Tucson. So ballpark aficionados get a look at two long-gone ballparks in Cleveland. Make that three long-gone ballparks, as the World Series footage also includes shots of Braves Field in Boston.

When this film was made, Hollywood was going through a trend of on-location movies. Urban crime movies were particularly popular, giving audiences a quasi-documentary look at New York ( The Naked City ), Chicago ( Call Northside 777 ), and New Orleans ( Panic in the Streets ), among other cities. I don’t know how much demand there was for a you-are-there experience of postwar Cleveland, but that’s what you get in The Kid from Cleveland .

The most remarkable aspect of the movie is the involvement of the entire Cleveland Indians team. Owner Bill Veeck, manager Lou Boudreau, “advisory coach” Tris Speaker, and GM Hank Greenberg all play themselves and have speaking parts.

Also credited with speaking parts are Bob Feller, Bob Lemon, Steve Gromek, Joe Gordon, and Gene Bearden, who also played himself in The [Monty] Stratton Story , also released in 1949, which must be a major league record for an active player portraying himself in movies in one season.

Finally, this brings us to Satchel Paige, who was in his “rookie” year in 1948. Paige is showcased in a scene where he teaches his hesitation pitch to the kid. After he claims it took him 20 years to master the pitch, hilarity ensues as Bob Feller says it was more like 30 years, and Steve Gromek ups the ante to 40! This banter was apparently the work of screenwriter John Bright.

Also of interest is the role of a local gangster played by infielder John Berardino, who was with the Indians at the time the movie was made. He is the only Indian who did not play himself. He would go on to a lengthy career in movies and TV after his 11-year playing career ended in 1952. He accrued 114 credits on the Internet Movie Database through 1996.

The rest of the Indians are on screen even if they don’t have speaking parts. They are part of the “30 godfathers” who come to the aid of Johnny Barrows. If my arithmetic is correct, this includes 24 players, player/manager Boudreau, coach Speaker, and the front office brain trust, Veeck and Greenberg, as well as the Indians’ play-by-play announcer, a fictional role essayed by George Brent, and a fictional parole officer played by Tommy Cook.

Now you might marvel at how much cooperation the filmmakers received from the Indians. It definitely surpasses whatever cooperation the Tribe offered to the Major League filmmakers four decades later. The link to Hollywood was likely Bob Hope, who purchased a minority interest in the team in 1946 when Bill Veeck took charge. Though born in England, Hope had grown up in Cleveland and had remained an Indians fan (remember, no big league ball in Hollywood ‘s backyard before 1958).

He does not appear in the film, however, possibly because he was under contract to Paramount and the film was produced by Republic Pictures. His tribal membership remained in good standing, however. Long after Hope had sold his interest in the Indians, he was invited back to Municipal Stadium to sing a baseball-oriented version of “Thanks for the Memories” before the last game played there on October 3, 1993.

At any rate, if you think it would be cool to see Satchel Paige play himself in a movie, or if you’re an old-school Indians fan still mourning the loss of Chief Wahoo, The Kid from Cleveland is a gold mine. Best of all, it’s available for free on YouTube.

Also available on the internet is the film with Satchel Paige’s next acting credit. In a sense, he trades in one uniform for another, as he plays a buffalo soldier ( i.e ., a black cavalry trooper) in The Wonderful Country , a 1959 western.

Unless you are a fan of Robert Mitchum and/or westerns, you likely have never encountered The Wonderful Country . Though hardly one of Mitchum’s best, it is passable entertainment. It does fit comfortably into Mitchum’s oeuvre , as he once observed, “I have two styles of acting – with or without a horse.” The film holds up better than The Kid from Cleveland , but that could be considered damning with faint praise. Nevertheless, when Mitchum and Paige are onscreen together, it is a rare opportunity to witness the interaction of two American pop culture legends whose climb to the top was against all odds. Paige’s wayward youth is no secret in baseball circles, but it was arguably no better than Mitchum’s.

In his mid-20’s Mitchum started his acting career playing cowpokes in Hopalong Cassidy movies and G.I.’s in World War II movies. A big career boost was Out of the Past , a 1947 film that is always included in Film Noir Top 10 lists, with some pundits asserting it belongs at the top of the list. Getting busted for marijuana in 1948 was avant-garde at the time and made him the darling of the Hollywood scandal sheets. An antihero before that term was coined, Mitchum fed off his bad boy image into his more mature years. Right up to the end he was adding to his legend. Suffering from lung cancer and emphysema on the final night of his life, his last act was to light up and puff away on an unfiltered Pall Mall.

Did Mitchum really do that or not? I don’t know, but it’s in his biography ( Robert Mitchum: Baby, I Don’t Care by Lee Server). Did Satchel Paige do half the stuff he supposedly did. I don’t know. For that matter, did Odysseus really do all that stuff in the Odyssey, or did Homer make it up? I don’t know. But I do know that ripping yarns, verifiable or otherwise, tend to gravitate towards legendary figures.

In The Wonderful Country , Satchel Paige acquits himself reasonably well as a cavalry sergeant, but it was his only attempt to play anyone other than himself. In fact, one of the curiosities of The Wonderful Country is how many people involved in the movie are better known for other pursuits. For example, Tom Lea, who appears in a bit part, was the author of the book on which the film was based – yet his main claim to fame was as a painter. Julie London, the female lead, was much better known as a songstress.

John Banner, who plays a German immigrant, went on to sitcom fame as Sergeant Schultz in the long-running comedy series Hogan’s Heroes . Screenwriter Robert Ardrey is better remembered today as a science writer ( African Genesis, The Territorial Imperative, et al ). Co-cinematographer Floyd Crosby was much better known for his work on Roger Corman’s B movies.

You might well wonder how the much-traveled Paige came to find himself wearing a cavalry uniform in Mexico in front of a movie camera in 1959. At the time it appeared that his baseball career was finally over, and it was time for a career change. Looking back on his 30+ years on the mound, perhaps he felt something was gaining on him.

His most recent gig had been with the Miami Marlins of the International League. In the mid-50’s, he again teamed up with Bill Veeck, who had signed him up for the Indians in 1948, and later for the St. Louis Browns from 1951 to 1953. By 1956 Veeck was running the Marlins, then the top farm team of the Phillies.

As a living legend in Miami, Paige was quite a drawing card. Ever the promoter, Veeck rented the Orange Bowl for an August 7 charity game against the Columbus Clippers. The crowd, estimated at 57,713, was far in excess of the capacity (13,000) of the Marlins’ home park, Miami Stadium. Paige came through for the big crowd, winning the game 6-2 and knocking in three runs with a double. At season’s end, Paige was 11-4 with a 1.86 ERA in 111 IP. Not bad for a 49-year-old, but routine for a legend.

Unfortunately, after the 1956 season Veeck sold the team to broadcasting pioneer George Storer. The 1957 season went well, but the 1958 season was another story, not so much because of Paige’s on-field performance as his off-field misadventures.

Early in the season, Paige was arrested for speeding and not having a valid driver’s license. During the season he tried management’s patience by showing up late for games and missing flights. An argument over money resulted in a 12-game suspension. To say the honeymoon was over was an understatement; the divorce decree was being finalized.

So, Paige was at liberty at the conclusion of the 1958 season. At the same time, Robert Mitchum was serving as executive producer as well as the star of a western to be filmed in the state of Durango, a popular location for westerns, in northwestern Mexico.

Other actors could have played the part of the cavalry sergeant, but Mitchum was a fan of Paige and had heard he was available. So, he made his pitch (presumably without hesitation) to Paige, who probably did not hesitate to accept the offer. After all, given the SAG-AFTRA union’s minimum rate ($3,756 per week in 2023) for a speaking part in a feature film and the number of days spent on location, it’s not a bad way to earn a tidy sum fairly quickly.

Paige was 52 years old at the time, but he was still in good shape. So, when he shows up in a sergeant’s uniform, he doesn’t come across as an old man so much as a seasoned trooper. A second career as a character actor might have been a possibility but Paige never pursued it. Or maybe it didn’t pursue him. Or maybe he wasn’t through with baseball. We know he returned to the mound at age 59 for one game with the Kansas City Athletics in 1967. The following year he was on the active roster (though he did not pitch) of the Atlanta Braves so he could qualify for a major league pension.

And that brings us to Paige’s final credit, this one behind the camera, namely as a writer for the 1981 TV movie Don’t Look Back: The Story of Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige. Now Paige didn’t sit down at a typewriter or some primitive word processor and churn out a screenplay. The script was written by Ronald Rubin who used Paige’s autobiography, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (co-authored with David Lipman) as the raw material.

Paige also got credit as a technical consultant and appeared briefly at the beginning and end of the movie. It’s worth pausing to note that the aforementioned Johnny Berardino also has a role in this movie, 32 years after he was in The Kid from Cleveland. tarring Lou Gossett as Paige, the film was aired on ABC on May 31, 1981.

Today a new movie is often in theaters at more or less the same time as it begins streaming. Forty years ago, however, there was a gulf between theatrical movies and made-for-TV movies. The former varied in quality but the latter were almost always mediocre. Commercial interruptions (fades to black followed by slow fade-ins) were baked into the script.

Occasionally, a TV movie would break out and even get play dates in a movie theater. Among them were Brian’s song , the story of the Chicago Bears’ Brian Piccolo, who died at age 26 of cancer; Duel , Stephen Spielberg’s thriller about a faceless truck driver and a monster truck harassing a motorist; and The Killers , a 1964 update of the Hemingway short story of the same name – with Lee Marvin dispatching crime boss Ronald Reagan in his last role before he took up politics. For the most part, however, TV movies were feature-length TV shows.

Leonard Maltin, who edits an encyclopedic movie guidebook, segregates TV movies from theatrical movies. While the theatrical releases get the standard one-to-four-star ratings, TV movies are singled out and classified as below average, average, and above average. Given the bigotry of low expectations theory, that is Maltin’s way of warning the viewer not to expect too much.

Don’t Look Back: The Story of Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige is only average by made-for-TV movie standards in 1981. If you happen across it, go ahead and watch it, but it isn’t worth searching for. Your time will be better spent tracking down The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings , a 1976 theatrical film in which Billy Dee Williams plays a Paige-like character during the heyday of the Negro Leagues.

Of course, if you are a true Seamhead, you may feel compelled to watch every baseball movie available. If you suffer from this particular form of OCD, then go ahead and search for Look Back: The Story of Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige .

Just as legends are often based on real people, movies are often based on true stories. But as we media consumers have learned through decades of experience, truth and truthiness are not the same thing. Plenty of sportswriters have built careers exploiting that difference.

Given the raw material supplied by one Satchel Paige, it’s hard to blame them.