Major Managers in Minor League History

December 16, 2023 by Frank Jackson · Leave a Comment

Every now and then we read about a scout, coach, or manager who is described as a baseball “lifer.” Well, that word also applies to someone serving a life sentence in prison. Read into that what you will.

Every now and then we read about a scout, coach, or manager who is described as a baseball “lifer.” Well, that word also applies to someone serving a life sentence in prison. Read into that what you will.

Being a lifer is better than being on death row, I guess. Of course, organized baseball does not have a literal death sentence. Nine men out (the Black Sox plus Pete Rose) might argue that there is a metaphorical death sentence. Being sent into exile is also possible, as Trevor Bauer would attest. What makes the baseball lifer unusual is that his sentence is self-imposed.

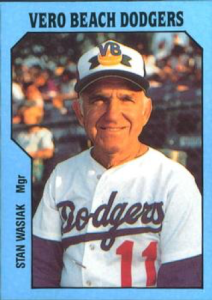

Typically, the baseball lifer is a traveling man. While he might spend his entire career with one organization, he will hire moving companies periodically or live out of a suitcase in a hotel. Consider the case of Stan Wasiak .

Now you might wonder who Stan Wasiak is – or was. Well, he is worthy of your attention for one reason: He won more minor league games than any other manager: 2,530, to be exact. Keep in mind that most minor league seasons are shorter than major league seasons, so he needed more seasons to reach that figure than a major league manager would need. Also, in the affiliated minor leagues, managers are more devoted to developing players than winning games, so playing to win is not a given. Had Wasiak been a major league manager, he would likely be in the Hall of Fame along with Connie Mack (3,731 wins), Tony LaRussa (2,884), and John McGraw (2,763).

Now I understand that the big leagues is THE SHOW, the minor leagues a sideshow. Nevertheless, let’s lift the flap on the tent and go inside to inspect Wasiak and take a peek at some other outstanding minor league managers.

Stan Wasiak was born in Chicago in 1920 and never played major league baseball. In fact, he never got close. He was a minor league catcher and infielder from 1940 to 1942. After three years in the military, he returned to the minors for three seasons. Following the 1949 season, Branch Rickey named him player/manager of the Dodgers’ Valdosta affiliate in the Class D Georgia-Florida League. The Valdosta franchise was just one of eight Class D teams affiliated with the Dodgers.

Believe it or not, in 1949 the Dodgers had a farm system of 27 teams, so it was easy for Wasiak to get lost in the shuffle. It was certainly a low-key beginning to a managerial career that would span 37 seasons. Now it would take up a lot of space to delineate all the stops during his career. So let’s just hit the highlights.

During most of his career, Wasniak was managing in the Dodger organization. The exceptions were 1955 through 1957 when he was managing Detroit affiliates, and 1966 through 1969 when he was managing White Sox affiliates. The highest level he reached was the Albuquerque Dukes of the Pacific Coast League from 1973 through 1976. His longest gig was managing the Vero Beach Dodgers from 1980 through 1986, the last year of his career. In 1985 he won the King of Baseball Award. Inaugurated in 1951, this annual award recognized lifetime achievement in the minor leagues. The award enjoyed a good run, lasting till 2019. After Covid passed, it did not return.

One might wonder why Wasiak never ascended to the big-league Dodgers. Well, one reason is that there was no room at the top. Walt Alston was the manager in Brooklyn and Los Angeles from 1954 through 1976. His successor was Tommy Lasorda, who led the Dodgers through 1996. Both are in the Hall of Fame. There was little to no chance of Wasiak or anyone else dislodging either.

Of course, any other major league team could have offered Wasiak a job in the Show – and perhaps some did so. When major league pay was much less than it is today, many minor league players preferred to stay with their old teams rather than move up to the big leagues. More than likely, the same applied to managers. Did Wasiak prefer to remain in the Dodger organization, bleed Dodger blue, and teach “The Dodger Way” even if he had zero chance of managing in Brooklyn or Los Angeles? Was there more status in being a Dodger lifer than, say, a Washington Senators lifer? Is there more status in being a janitor at Harvard than at Sleepytown Community College?

Another possible explanation for the baseball lifer is that a minor league manager often suffers from type-casting along with most of his players. It is pretty obvious that some minor league players are on a fast track to the major leagues. Top draft picks get the big bucks and the hoopla. Most of their teammates are second-class players. If they overachieve, they may one day arrive at the big leagues. Most of the others will wash out, but a select few will become organizational players.

They will remain in the minors longer than their peers and one day the organization will offer them jobs as coaches or managers with low-level minor league teams. They often end up as troubleshooters, moving up and down the minor league system, going wherever needed, as a coach, manager, or instructor. Their longevity indicates their proficiency, and some will even become big league coaches, but they will rarely be considered for major league managerial jobs. The long odds of an unheralded minor league player becoming a big-league player also apply to minor league managers with big-league aspirations.

This situation is not unique to organized baseball. In the movies, for example, you can be a superb supporting actor with multiple Oscars ( e.g ., Walter Brennan, who had three of them), but that doesn’t mean you will ever be promoted to leading man.

If you work in an office for a large or small business, you might have noticed the same phenomenon. Highly competent long-term employees often plateau while others are groomed for better things and rise accordingly. The lifers may hang around long enough to get a gold watch, but they will never be invited into the executive suite.

So one might well ask why Stan Wasiak would stick it out. The baseball season can be a grind. Those long bus rides are surely a downer, but those long off-seasons are pretty attractive. All things considered, managing a minor league team certainly beats pounding a keyboard in a cubicle, wielding a socket wrench on an assembly line, or driving a forklift in a warehouse.

Wasniak’s career is exemplary but it is not unique. In fact, there are 12 minor league managers with more than 2,000 victories. Most of them you’ve never heard of. A few are familiar names and some appeared briefly as major league managers. So let’s take a look at some of these long-lived lifers.

Right behind Wasniak is Bob Coleman, who toiled from 1919 through 1957 and garnered 2,496victories. He actually managed in the big leagues but with an asterisk. After five seasons with the Evansville Bees, the Boston Braves’ affiliate in the Three-I League, he was kicked upstairs to manage the big-league club. This was during the roster-depleted World War II seasons of 1943-1945, however, when baseball was in a holding pattern. Given the pre-war record of the Braves (next to last from 1939-1941), it could be argued that they were already in a holding pattern.

Right behind Wasniak is Bob Coleman, who toiled from 1919 through 1957 and garnered 2,496victories. He actually managed in the big leagues but with an asterisk. After five seasons with the Evansville Bees, the Boston Braves’ affiliate in the Three-I League, he was kicked upstairs to manage the big-league club. This was during the roster-depleted World War II seasons of 1943-1945, however, when baseball was in a holding pattern. Given the pre-war record of the Braves (next to last from 1939-1941), it could be argued that they were already in a holding pattern.

At any rate, very little was expected of Coleman. After three lackluster seasons (128-165), the Braves fired him as a manager but kept him on the payroll and gave him his old job back with Evansville. Of the final 12 years in his managerial career, 11 were with the Evansville Braves (the outlier year was 1950 when he managed the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association).

Mike Kelleyplayed one year in the big leagues (with the Louisville Colonels of the National League in 1899) but never made it to the big leagues as a manager. Not that he was stuck in the sticks, as, 29 seasons of his 31-year career (1901-1931) were spent in the American Association, entirely in the Twin Cities area, as he managed both St. Paul and Minneapolis (five championships with the former, none with the latter). The rivalry was known as the Streetcar Series and double-headers were often split between the two cities.

So home or away, Kelley was always at home. This sort of stability was highly unusual, as a minor league manager is usually all too familiar with the old real estate maxim: “Relocation, relocation, relocation.” Altogether, Kelley won 2,390games. Since 2,226 were for Minneapolis and St. Paul, it is fitting that he was one of the early (1959) inductees into the Minnesota Sports Hall of Fame, which was established in 1958.

Since the death of Tommy Lasorda in 2021, Buddy Baileycan lay claim to being the most successful living manager born in Norristown, Pennsylvania. He is the active leader in minor league victories with 2,357(that’s not counting his victories in the Venezuelan Winter League). Bailey got his start in 1983 with the Pulaski Braves. Altogether, he served 8 seasons with the Braves organization, 14 seasons with the Red Sox (he spent the 2000 season as a bench coach with the big club), and 18 seasons with various Cubs affiliates.

He is currently skippering their Myrtle Beach affiliate in the Carolina League. This brings up the subject of perks in minor league ball. Who wouldn’t want a summer job in Myrtle Beach? I don’t know if Buddy Bailey is into saltwater fishing or body surfing, but if he’s a golfer it’s noteworthy that there are more than 80-some courses in the Myrtle Beach area.

Rick Sweet, current manager of the Nashville Sounds of the International League, has 2,268minor league victories, second only to Buddy Bailey among active minor league managers. His big-league career as a switch-hitting catcher was modest, consisting of just three seasons (1978, 1982 and 1983), and 815 plate appearances. After serving as a scout for two years, he started his managerial career in 1987 with the Bellingham Mariners of the Northwest League, but most of his career, 23 seasons to be exact, has been at the Triple-A level (Tucson, Ottawa, Portland, Louisville, Colorado Springs, San Antonio, and Nashville), and he has won four Manager of the Year awards at that level.

Now 71 years old, he has managed the Nashville Sounds for four seasons, winning more games (321) than any other manager in the history of the franchise. It is curious that so many major league teams have named him to manage their highest affiliates (in 2022 he won the Mike Coolbaugh Award, which is a more recent lifetime achievement award for minor league lifers), yet not one has elevated him to the big time. If Sweet ever had major league ambitions, he has likely outlived them. Yet he still has a chance to write his name into the record book. Will he hang on longer than Buddy Bailey to become the leading active manager, or perhaps even the all-time leader? Stay tuned.

Next on the list is Johnny Liponwith 2,185victories. If the name sounds familiar, it’s probably because he played nine seasons (1942, 1946, and 1948-1954) in the big leagues as an infielder, mostly with the Tigers. His minor league managerial career began in 1959 with the Cleveland Indians organization, starting with the Selma Cloverleafs of the Alabama-Florida League. In 1968, he was kicked upstairs to the big Tribe, serving as a coach in Cleveland through 1971. After manager Alvin Dark was fired, Lipon managed the Indians for the last two months of the 1971 season.

His record (18-41) was not encore-worthy, so he was replaced by Ken Aspromonte in 1972. Returning to minor league ball, Lipon remained there through 1992, managing at various way stations up and down the Pittsburgh and Detroit organizations. His last stop was the Lakeland Tigers of the Florida State League in 1992. In 1995 he joined Stan Wasiak as a winner of the King of Baseball award.

Spencer Abbottstarted his managerial career with Fargo of the Northern League in 1903 and retired at age 70 after his 1947 season with the Charlotte Hornets of the Tri-State League. His stops along the way included such colorfully named teams as the Hutchinson Salt Packers (1906), the Wellington Dukes (1910), the Lyons Lions (1911), the Pasadena Millionaires (1913), and the Santa Barbara Barbareans (1913).

He also logged time in some of the upper echelon minors: the International League (1923-1925 and 1927), the American Association (1926), and the Pacific Coast League (1931-1933, 1937). That was as high in the food chain as he got as a manager, though he did serve as a coach for the Washington Senators in 1935. So he had to be content with 2,180minor league victories.

Before he got into pro baseball, Butch Hobsonfollowed in his father’s footsteps and played baseball and football at the University of Alabama. He served as a backup quarterback under Bear Bryant and got some playing time in the 1972 Orange Bowl. He played eight years in MLB, including three as the starting third baseman for the Boston Red Sox. He finished his playing career with three seasons (1983-1985) as a member of the Columbus Clippers, the International League affiliate of the Yankees. He began his managerial career with the Columbia Mets of the South Atlantic League in 1987.

Returning to the Red Sox organization, he managed their New Britain and Pawtucket affiliates before returning to Boston to manage the Red Sox for three seasons (1992-1994). After a 54-61 record in the strike-shortened 1994 season, he was replaced by Kevin Kennedy. Hobson then returned to minor league managing. Since 1996 when he was involved in a cocaine bust while managing the Phillies’ Triple-affiliate at Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, his employment in affiliated ball has been scant. Since 2000, all of his gigs have been in indy ball, save for 2017 when he managed the Kane County Cougars of the Midwest League.

Altogether, he spent 15 seasons in the Atlantic League (6 with the Nashua Pride, 3 with the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs, and 6 with the Lancaster Barnstormers), 2 seasons in the Can-Am Association (with Nashua), and 6 seasons with the Chicago Dogs of the American Association. Hired as the skipper for the Dogs’ inaugural season of 2018, he is the only manager in the franchise’s history. Remaining with the Dogs in 2024, he is currently sitting on 2,142victories. His son, K.C. Hobson, has played minor league ball since 2010, most recently (2023) with the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs of the Atlantic League.

As a rookie outfielder with the famed 1914 Miracle Braves, Larry Gilbertwas the first native of New Orleans to play in the World Series. After hitting a less-than-miraculous .151 in 121 plate appearances in 1915, he was sent back to the minors. In 1917 he returned to New Orleans, where he played for the Pelicans of the Southern League. Serving as player-manager from 1923-1925, he remained as manager through 1938. Remaining in the Southern Association, he managed the Nashville Volunteers from 1939 through 1948. Nashville valued his presence so much that he was reportedly the highest paid manager in all of baseball.

Understandably, he rebuffed offers from major league teams. It was a remarkably stable career for a minor league manager: one league, two teams, 25 seasons, 2128victories. He was inducted into both the Louisiana and Tennessee Sports Halls of Fame, as well as the Greater New Orleans Baseball Hall of Fame. To this day, you can watch amateur baseball at Larry Gilbert Stadium in New Orleans. His sons, Charlie and Tookie Gilbert, both played major league baseball.

Bill Clymerplayed three games with the 1891 Philadelphia Athletics (then a member of the American Association, which was considered a major league) at age 18. He went 0 for 11, and that was the end of his major league playing career. He then began a minor league playing career that lasted through 1897. He first managed in the minors for the Rochester Patriots/Ottawa Wanderers at age 25 in 1898, embarking on career that lasted till 1932. From 1900 through 1906 he was a player-manager for the Wilkes-Barre Coal Barons, the Louisville Colonels, and the Columbus Senators. He continued as a manager through 1932, ending his career with the Scranton Miners of the New York-Penn League. Along the way he won 2,122games.

Although he is not at the top of the list of career victories, a good case could be made that Jack Dunnis the heavyweight champ of minor league managers based on his career winning percentage of .579. He is renowned as the man who signed Babe Ruth to his first professional contract (and served as his guardian) in 1914 with the minor league Baltimore Orioles, but there is much more to his career than that. Dunn was both a pitcher and a position player during his eight years (1897-1904) in the majors. In the field he played mostly third base and shortstop, but he also logged time at second base and the outfield, giving him broad experience that undoubtedly helped him as a manager.

He began his managerial career in 1905, spending two seasons with Providence in the Eastern League. In 1907 he transferred to the Baltimore Orioles who at the time were in the same league. In 1910 he took over as team owner (in 1913 the Eastern League rebranded itself as the International League to reflect the addition of teams in Toronto and Montreal) while continuing as manager. Dunn remained in Baltimore through 1928 save for 1915 when he moved the franchise to Richmond because of competition from the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins.

He was not there long, however, as he sold his interest in the Richmond club, bought the International League’s Jersey City franchise, and moved it to Baltimore in 1916 after the Federal League folded. Altogether, he won 1,900 games for Baltimore teams and 2,107total). Next to signing Babe Ruth, his next biggest claim to fame is managing the Orioles to seven consecutive pennants (never achieved before or since by any manager at any level) from 1919 through 1925, finally dropping to a mere second place in 1926. During this 8-year stretch he won more than 100 games every year, peaking with 119 in 1921. Along the way he also won three (1920, 1922 and 1925) Little World Series, as the post-season matchup between the International League and American Association champs was called. A number of pundits asserted that during their dynasty years, the Orioles were as good as if not better than a number of major league teams.

Unlike most minor league owners, Dunn did not need to sell his best players to the major leagues to stay afloat. Famously, Lefty Grove won 108 games for the Orioles in five seasons before he finally made his major league debut with the A’s in 1925 and began his long march toward 300 MLB victories. Unfortunately, the end of Dunn’s career coincided with the end of his life, as he died at age 56 following the 1928 season. He fell victim to a heart attack while on horseback, so he was literally and figuratively in the saddle right up to the end.

Ironically, he had turned down an offer to manager the Boston Braves earlier in the year. Had he lasted as long as the men listed above, he might have finished at the top of the list. Since he won 1,489 games in the International League, it is no surprise that he was inducted into that league’s Hall of Fame in 1950. The Dunn family influence did not die with Jack Dunn, however, as his wife Mary inherited the team and remained team owner till her death in 1943, at which time his grandson, Jack Dunn III, took over. He managed the team in 1949 and later became the traveling secretary for the major league Orioles in 1954 after the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore.

Lefty O’Doulwas a renowned hitter, hitting coach, and baseball ambassador to Japan (he was the first American inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame). Though he didn’t arrive in the big leagues to stay till he was 31 in 1928, he won National League batting titles in 1929 and 1932, and had a .349 lifetime BA. His best season was 1929 when he batted .398 for the Phillies. With one more hit, he would have joined the charmed .400 circle (.3996865, to be exact, which would round off to .400). His 254 hits that season remains the NL record (Bill Terry of the Giants tied the record just one year later).

O’Doul’s achievements at the major league level tend to overshadow his lengthy career as a minor league manager. He won 2,094games, all but 583 of them with his hometown San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. His managerial career with the Seals ran from 1935 to 1951, but he also managed the minor league San Diego Padres (1952-1954), the Oakland Oaks (1955), the Vancouver Mounties (1956), and the Seattle Rainiers (1957). Many pundits feel he deserves a place in Cooperstown.

Fittingly, he does have a spot in the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame, since all his managerial victories were in the PCL. Actually, his playing career alone made him worthy of enshrinement as he hit .353 during his PCL tenure. Notably, of his 1,132 hits in that league, 309 were in 1925 when he played for the Salt Lake Bees. His sports bar, Lefty O’Doul’s Restaurant and Cocktail Lounge, was a longtime favorite in San Francisco from its opening in 1950 till it closed in 2017.

Andy Gilbert(no relation to the aforementioned Larry Gilbert) won 2,009games in 9 leagues in 29 seasons. His major league playing career was brief, one hit in 12 at bats with the Boston Red Sox. His career could be described as a cup of coffee in 1942 and a refill in 1946, with military service in-between. He spent most of 1946, as well as 1947 through 1949 playing Triple-A ball. After three seasons with the Giants’ Triple-A affiliate, the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, he accepted a position as player-manager with the Springfield Giants of the Class D Ohio-Indiana League.

He continued to manage in the Giants system, closing out his playing career at age 40 in 1955, save for one game in 1959. From 1972 to 1975, he served as a coach with the big club. He remained with the Giants organization through 1980, when he managed the Shreveport Captains of the Texas League. After 31 seasons collecting a paycheck from the Giants, he spent two seasons with the Savannah Braves of the Southern League.

Before ending this essay, it is worth listing three honorable mentions who are still active and within striking distance of 2,000 victories.

Tom Kotchmanhas been a minor league manager for 42 years. After two nondescript seasons as a player at Class A, he embarked on his managerial career with the Auburn Red Stars of the New York-Penn League in 1979. In 1984 he took the reins of the Redwood Pioneers, an Angels’ affiliate. He managed at various Angel farm teams through 2012. Since 1990 he has managed exclusively in short-season leagues, thus hindering his ability to amass victories.

Nevertheless, he has accrued 1,964wins. Needing just 36 wins to reach 2,000, he could do just that with a good season in 2024 (he is currently with the Florida Complex League Red Sox). Kotchman was in the inaugural class of inductees into the Professional Baseball Scouts Hall of Fame in 2008. In 2017 he won the Tony Gwynn Lifetime Achievement Award bestowed by Baseball America . His son Casey played 10 seasons (2004-2013) in the major leagues.

Stan Cliburnis a classic minor league lifer, based on a lengthy career as a player as well as a manager. He played just part of one season (1980) in the majors as a backup catcher with the Angels, but 14 in the minors (1974-1987), nine in the Angels’ system and five in the Pirates’ system. Following the 1987 season he went into managing and has remained there ever since, splitting his time between affiliated ball (16 seasons) and indy ball (15 seasons), winning 1,962games along the way. Since 2019, he has been the manager of the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs of the Atlantic League.

He should surpass 2,000 victories at some point in the 2024 season. He is the identical twin brother of Stu Cliburn, who pitched three seasons with the Angels and is currently the pitching coach for Butch Hobson’s Chicago Dogs. Stan himself worked for Hobson in 2014 as a hitting coach with the Lancaster Barnstormers.

John Shoemakerhas bled Dodger blue at assorted minor league venues, 4 as a player, and 29 as a manager. After serving as hitting coach for the Vero Beach Dodgers (where Stan Wasiak was his manager), he was promoted to manager in 1987 at age 30 and went on to manage at every level of affiliated minor league ball. He is currently the manager of the Cucamonga Quakes of the Class-A California League, who won the league championship in 2023.

At age 67, Shoemaker has 1,780victories. He has a shot at 2,000 if he hangs on a few more years and the Dodgers continue to supply him with decent players. Like Mike Sweet (see above), he also won the Mike Coolbaugh Award (in 2015). Based on his record with the Jacksonville Suns (two championships in five seasons), he was named to the Southern League Hall of Fame in 2016. Fun fact: Shoemaker, who was awarded a basketball scholarship at Miami University, was drafted by the Chicago Bulls in the 6 th round of the 1978 NBA draft.

So there we have it, an assortment of lifers who have spent a big chunk of their lives away from the glare of the major league spotlight. For the most part, their achievements have been unsung. But there is no doubt they made major contributions to the development of countless major league players who have gone on to fame and fortune.