The 400 K Club

December 31, 2023 by Frank Jackson · Leave a Comment

At the end of the 1965 season, Sandy Koufax

, though just one year away from retirement, was riding high. He led the National League in wins (26), ERA (2.04), and complete games (27) while setting a major league record with 382 strikeouts. Less than a decade later (1973), Nolan Ryan

astounded the baseball world by striking out 383 batters on his way to a 21-16 record. It seemed just a matter of time before some stud with a golden arm broke the 400K barrier. Randy Johnson

was a noteworthy challenger. He eclipsed 300 six times, peaking at 372 in 2001.

At the end of the 1965 season, Sandy Koufax

, though just one year away from retirement, was riding high. He led the National League in wins (26), ERA (2.04), and complete games (27) while setting a major league record with 382 strikeouts. Less than a decade later (1973), Nolan Ryan

astounded the baseball world by striking out 383 batters on his way to a 21-16 record. It seemed just a matter of time before some stud with a golden arm broke the 400K barrier. Randy Johnson

was a noteworthy challenger. He eclipsed 300 six times, peaking at 372 in 2001.

So after half a century, Ryan’s 383 remains the gold standard. In fact, it seems safer now than it does when he set the record. Today batters are striking out more than ever but starting pitchers aren’t finishing what they started, so relief pitchers are garnering more and more strikeouts. Ryan threw 326 innings in 1973. The 2023 MLB leader in IP was Logan Webb with 216 – 110 fewer innings. So forget about anyone reaching 400 in MLB. The best total since Randy Johnson retired was 326 by Gerritt Cole in 2019, but that’s a long way from Ryan’s record of 383, not to mention 400. But the 400K barrier has already been breached by major league pitchers…but they didn’t do it in the major leagues.

Consider the case of Virgil Trucks. First of all, gotta love a name like that. It could be a two-word sentence or the name of a dealership. Actually, for many years right-hander Trucks was a fixture in the American League. Over a 17-year career, mostly with the Tigers, Trucks…well, kept on truckin’: He fashioned a 177-135 record with a 3.39 ERA. He had two All-Star seasons and one 20-win season. Yet a case could be made that his best season was in 1938, his first year as a pro. Admittedly, he started at the bottom.

Hurling for Andalusia (a small town in south central Alabama) in the Class D Alabama-Florida League, Trucks won 25 and lost 6 with a 1.25 ERA and a WHIP of .982 in 273 innings. As impressive as these stats are, the real eye-opener was his accumulation of 418 strikeouts. That averages out to 13.8 per 9 innings. Observers probably wondered what he would do in 1939, but while he was still effective (16-10 with a 2.82 ERA with two teams, Alexandria of the Class D Evangeline League and Beaumont of the Class A1 Texas League), he wasn’t mowing ‘em down. The same was true in 1940 with Beaumont, but in 1941 with Buffalo of the Double-A International League, he struck out 204 in 204 IP. At the MLB level his best total was 161 in 236.2 IP in 1946 for Detroit. That 6.1 SO9 rate tied his personal best at the MLB. Not bad but a long way from a strikeout record.

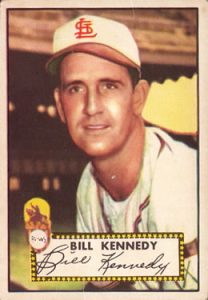

As impressive as Trucks’ 418K achievement is, it was not the highest total ever achieved in professional baseball. Surpassing that total in 1946 was William Aulton Kennedy, who struck out 456 batters while pitching for the Rocky Mount Rocks of the Class D Coastal Plain League. To say this was unexpected would be an understatement. Originally signed by the Yankees in 1939, he was released from the St. Louis Cardinals’ extensive farm system early in the 1946 season. It’s not hard to imagine the Cardinals’ GM, William Walsingham, Jr. having some sleepless nights as Kennedy’s strikeout total mounted. But the 1946 Cardinals won the World Series (over the Red Sox), which covers up any number of mistakes or regrets.

Actually, Walsingham need not have worried. Unlike Trucks, Bill “Lefty” Kennedy did not have a lengthy or notable career. His modest big league career fairly screams “JOURNEYMAN!” In eight seasons on the mound he won 15, lost 28, and fashioned an ERA of 4.73. He struck out 256 batters in 464.2 IP, which works out to 5 SO per 9 IP, not exactly blowing ‘em away.

Kennedy had the good fortune to be a rookie on the 1948 Cleveland Indians; unfortunately, he was dealt to the St. Louis Browns in mid-June (he had an ERA of 11.12 in six appearances) long before the Tribe won the World Series. In return for Kennedy and $100,000, the Indians received pitcher Sam Zoldak, something of a journeyman himself, and arguably not worth the extra $100,000.

Being traded to the St. Louis Browns was like being sent to the eighth circle (fraud) of Dante’s hell, as the Browns were masquerading as a major league team. Yet Kennedy remained with the franchise through 1951. During that span he had a record of 12-25. In his two busiest seasons (132 IP in 1948 and 153.2 in 1949), his ERA was in line with his career ERA. After spending almost all of 1950 in the minors, he returned to the Browns in 1951 with a disappointing (1-5, 5.79 ERA) season – even by Browns’ standards. He was returned to the minors in mid-July, which means he missed out on the Eddie Gaedel sideshow, which occurred on August 19.

With the White Sox in 1952, Kennedy appeared to have hit his stride at age 31. Coming out of the bullpen save for one start, he led the AL in appearances (47) and fashioned a 2.80 ERA in 70.2 IP. If he thought he had found a home at Comiskey Park, however, he was wrong. During spring training of 1953 he was traded (along with Marv Grissom and Hal Brown) to the Boston Red Sox for hard-hitting shortstop Vern Stephens, an eight-time All-Star who had led the AL in RBIs in 1944, 1949, and 1950, but had begun to decline (in fact, the White Sox put him on waivers before the season was over).

After 16 games with the Red Sox in 1953 Kennedy was returned to the minors (Triple-A Louisville). After learning to throw a screwball while pitching for the Seattle Rainiers (a Cincinnati affiliate) in the Pacific Coast League, he earned another chance in MLB. The Reds brought him back to the big leagues for brief stints in 1956 and 1957, but the results were unimpressive. By then he was 36 years old, a good age to call it quits, but he went back to Seattle and remained there through 1960. So you have to give Kennedy credit for hanging in there.

It’s possible that Kennedy’s minor league achievement in 1946 kept him in the game longer. GMs might have been curious to see if his dominance might re-assert itself. Of course, since he was a left-hander, and since southpaws are less plentiful than right-handers and tend to be late bloomers (Sandy Koufax being the textbook example), he might have had a longer shelf life than a right-hander anyway.

Though Kennedy’s big-league career has faded into obscurity, that one season with the Rocky Mount Rocks gave him a place in baseball history. He was assured of baseball immortality, albeit minor league, even after he joined the invisible choir of Dead Kennedys on April 9, 1983.

Hard to believe, but Kennedy’s 456 Ks is not at the top of the leaderboard. To find the top dog, we must go back more than a century, to 1907 and the Mattoon Giants of the Class D Eastern Illinois League.

The name Grover Cleveland Lowdermilk sounds like a character in one of W.P. Kinsella’s fanciful baseball stories, but he was a real right-handed pitcher (1885-1968) with a fastball that inspired comparisons to Walter Johnson’s. While pitching for Mattoon, he garnered 458 Ks on his way to a 33-10 record with an ERA of 0.93. For good measure, he struck out 7 during a short early-season stint with the Class B Decatur (IL) Commodores of the Three-I League. That makes a grand total of 465 for the 1907 season. Keep in mind that this was during the Deadball Era when contact hitting was supposedly all the rage.

As with many a young pitcher blessed (?) with an overpowering fastball, Lowdermilk was a plagued by wildness – not Steve Dalkowski off-the-chart wildness, but just-off-the-plate wildness. So renowned for wildness was Lowdermilk that during his career, his name was a slang term for a pitcher who couldn’t throw strikes. According to Paul Dickson’s definition in his Baseball Dictionary :

Eponymous term for a pitcher given to wildness. From Grover Cleveland Lowdermilk whose lackluster pitching (career record of 23-39 between 1909 and 1920, with 296 strikeouts and 376 bases on balls [in 590.1 IP]) was characterized by legendary wildness.

Obviously, this is not a legacy any ballplayer would want but the term has fallen into disuse. Unfortunately, Lowdermilk never lived down having to pay second fiddle to that more famous Presidential namesake, namely Grover Cleveland Alexander.

Like Kennedy, Lowdermilk can be classified as a journeyman. His MLB strikeout totals were so-so and his career SO9 was only 4.5. The highlight of his career was his participation with the 1919 Black Sox after his contract was purchased from the Browns in mid-May. He actually had a decent season with the Sox, going 5-5 with a 2.57 ERA in 96.2 IP. He was limited to one inning in the World Series, however, entering Game One in the bottom of the 8 th with the Reds holding a big lead.

Lowdermilk was never implicated in the fixing of the World Series. He was 34 years old, however, so his career was all but over anyway. In 1920 he got off to a bad start and was sent down to the minors, where he spent the rest of his career, mostly with the Minneapolis Millers of the Double-A American Association. He called it quits in 1922 at age 37.

Lowdermilk’s MLB career ERA of 3.58 was not atrocious, though it was a bit high for the Deadball Era. As mediocre as his overall record was, he was capable of occasional flashes of brilliance (he once pitched both ends of a double-header shutout against the Cardinals in a St. Louis City Series). So you can’t blame managers and front offices for being intrigued by Lowdermilk. He probably remained in the game so long because the various MLB teams he pitched for (Cardinals, Cubs, Browns, Tigers, Indians, White Sox) hoped his blazing fastball would find the strike zone under their tutelage.

One wonders what went through the minds of these pitchers during their 400+ K seasons. Did they feel like supermen when they took the mound? Or did they tell themselves, no, it can’t be this easy? When Lowdermilk retired, he probably never figured anyone would ever challenge his mark. Yet he lived long enough to hear about the feats of Kennedy and Trucks.

Well, I don’t know that anyone will live long enough to witness the next pitcher to hit the 400-strikeout mark in any league, major or minor. If you watch the affiliated minor leagues, you are probably aware that the major league teams control the pitching staffs and have pitch counts imposed on their prospects. This is not the case in the independent minor leagues, but they play shorter seasons. So today a strikeout machine in the minors could attain an outstanding SO9 score without coming close to 400 or even 300 strikeouts. But there is a solution to this problem.

As you may have noticed, all the 400+ strikeout seasons occurred in Class D ball. So the logical solution is to bring back Class D minor leagues! In fact, if the aforementioned W.P. Kinsella were still around, he might have found the seeds of a story in the resurrection of a Class D minor league – a magical, mystery league where anything can happen!

Imagine an America criss-crossed with Class D baseball franchises. Imagine minor league ball in places you didn’t know were places…Smackover, Arkansas…Truth or Consequences, New Mexico…Intercourse, Pennsylvania…Santa Claus, Indiana…Cut and Shoot, Texas…all with professional baseball.

Then think of all the potential strikeouts.

Somewhere out there another baseball legend, his hour come round at last, is slouching towards Bethlehem (Pennsylvania?) to be born.