- Home

- Introduction, Update Information, Links

- The Super Seventies "Classic 500"

- Readers' Favorite Seventies Albums

- Seventies Single Spotlight

- The Top 100 Seventies Singles

- Favorite Seventies Artists In The News

- Seventies Almanac - Year By Year

- Seventies Singles - Month By Month

- Seventies Albums - Month By Month

- Seventies Daily Music Chronicle

- Seventies Superstars In Their Own Words

- The Super Seventies Archives

- Seventies Trivia Quizzes & Games

- Seventies MIDI Jukebox

- The Super Seventies Bookstore

- The Super Seventies Photo Gallery

- Seventies' Greatest Album Covers

- Popular Seventies Movies & TV

- Seventies Celebrity Portrait Gallery

- Seventies Lyrics Hit Parade

- Top Seventies Artist Music Videos

- Seventies Usenet Music Forums

- Seventies Smiley Calendar

- EXTRA!

- Superseventies.com Facebook Page

- Superseventies.com Reddit Discussions

- The Super Seventies Blog

- Tweet The Seventies

- RockSite InfoBank

- Beatlefan Site

- Thanks For Your Support! / Top Sellers

- Search The Rock Site/ The Web

![]()

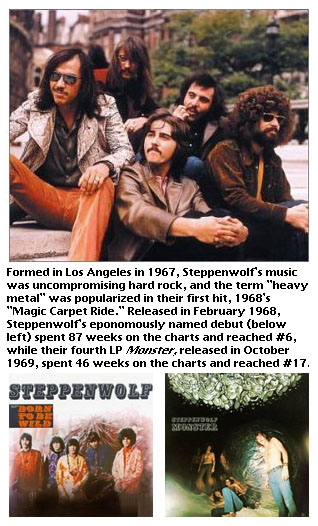

Hard-rock outfit Steppenwolf's 1969 track "Monster/Suicide/America" rings truer than ever in 2007.

by David Fricke

in Rolling Stone

![]() merica, where are you now?/ Don't you care about your sons and daughters?/ Don't you know we need you now?/ We can't fight alone against the monster": That chorus is the big finale of the best rock & roll song about the precarious state of our union, a three-part suite more than nine minutes long and originally released in late 1969 by the hard-rock hit machine Steppenwolf. "Monster/Suicide/America" ate up most of Side One of the group's fourth straight Top Twenty studio LP, Monster

(Dunhill). The album is still in print (and on iTunes). XM Satellite Radio's Deep Tracks channel has the title track in periodic rotation. But I have gone back to the "Monster" opera a lot

on my own in recent years, because the history in it is repeating itself so precisely.

merica, where are you now?/ Don't you care about your sons and daughters?/ Don't you know we need you now?/ We can't fight alone against the monster": That chorus is the big finale of the best rock & roll song about the precarious state of our union, a three-part suite more than nine minutes long and originally released in late 1969 by the hard-rock hit machine Steppenwolf. "Monster/Suicide/America" ate up most of Side One of the group's fourth straight Top Twenty studio LP, Monster

(Dunhill). The album is still in print (and on iTunes). XM Satellite Radio's Deep Tracks channel has the title track in periodic rotation. But I have gone back to the "Monster" opera a lot

on my own in recent years, because the history in it is repeating itself so precisely.

The music -- written by singer John Kay, drummer Jerry Edmonton, bassist Nick St. Nicholas and guitarist Larry Byrom -- has lost none of its muscular drama: the bright, winding guitar riff and power-chord gunfire in "Monster"; the heavy-blues hell of "Suicide"; the gospel-army glow of the vocals and Goldy McJohn's organ in that last-stand chorus of "America." But Kay's acute, snarling rage at the runaway greed, disastrous imperialism and daily betrayals of civil rights is startling in its prescience: "Its leaders were supposed to serve the country/ But now they won't pay it no mind... Now we are fighting a war over there/ No matter who's the winner/ We can't pay the cost." When Kay sings, "The police force is watching people," he has the biography to back it up. Born in 1944 in what would soon become Communist East Germany, he escaped with his mother to West Germany four years later.

Named after Herman Hesse's 1929 novel of transformation and dementia, Steppenwolf are most remembered for their 1968 outlaw-life anthems "Born to Be Wild" and "Magic Carpet Ride." But they were also a gnarly R&B band -- see the cover of Don Covay's "Sookie Sookie" on 1968's Steppenwolf

-- and could be impressively weird. A 1971 B side, "For Madmen Only" (a title also borrowed from Hesse's book), was 8:46 of feedback and organ drone. And while Rolling Stone

's 1970 review of Monster

mocked its politics ("The words get in the way"), Kay's best early writing was vigorously partisan songs of warning and resistance: "Don't Step on the Grass, Sam," on 1968's The Second.

But "Monster/Suicide/America" is as powerful and right

today as it was thirty-seven years ago. And I will keep going back to it -- at least until history stops repeating itself.

![]()

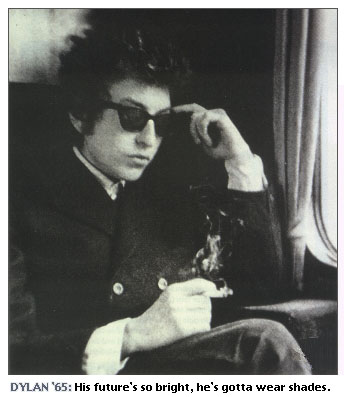

An old-school Dylan doc goes on the road with the rugged folk hero on his track to stardom.

by Ken Tucker

in Entertainment Weekly

Bob Dylan: Don't Look Back

Deluxe Tour Edition

Unrated, 95 mins., 1967

(New Video Group)

![]() he rerelease of D.A. Pennebaker's '67 documentary Don't Look Back

arrives in a box as thick as your average Charles Dickens novel. The film -- an impressionistic look at Bob Dylan's 1965 England tour, shot in black and white, with Dylan frequently in black moods and nearly always exhibiting white-hot creative power -- remains a mesmerizing document. It's artfully, intentionally casual, "sloppy" only in the sense of tricking you into thinking it was made up on the spot in the way the newly electric Dylan was making up a fresh definition of rock stardom, and the film reveals new details with every viewing. (I had never caught, for example, that after Dylan sings "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" in a hotel room, the British Dylan wannabe Donovan murmurs fawningly, improbably, "I used to know a girl named Baby Blue.")

he rerelease of D.A. Pennebaker's '67 documentary Don't Look Back

arrives in a box as thick as your average Charles Dickens novel. The film -- an impressionistic look at Bob Dylan's 1965 England tour, shot in black and white, with Dylan frequently in black moods and nearly always exhibiting white-hot creative power -- remains a mesmerizing document. It's artfully, intentionally casual, "sloppy" only in the sense of tricking you into thinking it was made up on the spot in the way the newly electric Dylan was making up a fresh definition of rock stardom, and the film reveals new details with every viewing. (I had never caught, for example, that after Dylan sings "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" in a hotel room, the British Dylan wannabe Donovan murmurs fawningly, improbably, "I used to know a girl named Baby Blue.")

Pennebaker's 16mm handheld camera doesn't merely follow Dylan on stage, where, solo with acoustic guitar and harmonica, he bleats out an array of songs including some that would soon change rock history with Bringing It All Back Home.

It also captures Dylan interacting with the public: joking sweetly with teen female fans; tearing a student journalist a new one just because he can (Dylan's deadpan cruelty is as devastating as some of his music). And the film takes you into London business offices, where Dylan's malicious-cherub manager, Albert Grossman, is caught jacking up his client's concert fee with sour skill.

Pennebaker's 16mm handheld camera doesn't merely follow Dylan on stage, where, solo with acoustic guitar and harmonica, he bleats out an array of songs including some that would soon change rock history with Bringing It All Back Home.

It also captures Dylan interacting with the public: joking sweetly with teen female fans; tearing a student journalist a new one just because he can (Dylan's deadpan cruelty is as devastating as some of his music). And the film takes you into London business offices, where Dylan's malicious-cherub manager, Albert Grossman, is caught jacking up his client's concert fee with sour skill.

If you compare Don't Look Back with Martin Scorsese's superb, more conventionally structured No Direction Home (2005), which spans decades with masterful ease, you might be tempted to downgrade Don't Look Back 's achievement. But it's apples and oranges. Pennebaker was creating a new form of documentary on the fly, a method he'd pursue in rock docs like Monterey Pop (1968) and his really-needs-a-DVD-distributor Town Bloody Hall (1979), about a feminism debate between Norman Mailer and Germaine Greer.

Yet Don't Look Back

doesn't benefit from its "65 Tour Deluxe Edition" padding. The second disc of outtakes doesn't add anything to our understanding of Dylan; the "companion book" is a transcript of the dialogue; the photo flip-book of the famous opening -- Dylan's flash-card version of "Subterranean Homesick Blues" -- is pointlessly cutesy. The commentary by Pennebaker and road manager Bob Neuwirth (Dylan's longtime friend) is too kindly, softening the hard edges of Dylan's temper to no good purpose. But nothing can minimize Dylan in top form, as when he tells a stupefied reporter, "I'm just as good a singer as Caruso." That this both is true and not true, simultaneously, is one aspect of what makes Dylan great. Buy the remastered single-disc edition

to look back in awe. B

![]() Reader's Comments

Reader's Comments

No comments so far, be the first to comment .

![]() Best of EXTRA!

| EXTRA!

| Main Page

| Seventies Single Spotlight

| Search The RockSite/The Web

Best of EXTRA!

| EXTRA!

| Main Page

| Seventies Single Spotlight

| Search The RockSite/The Web