☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

茶道の精神

茶道の歴史

The Book of Tea #Audiobook

お吟さま – Ogin-sama - Love Under the Crucifix (1962) Kinuyo Tanaka

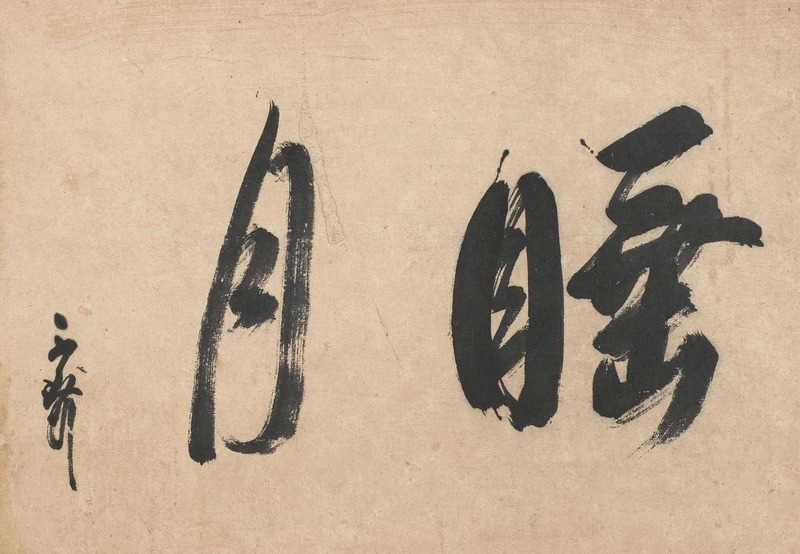

Suigetsu (Intoxicated by the Moon) paper hanging scroll for a tea ceremony

by Sen no Riky?, c. 1575

by Sen no Riky?, c. 1575

茶道の精神

茶道の精神を表す四つのキーワードである「和敬清寂」、「利休七則」、「一期一会」、「わび・さび」について考える。

https://www.youtube.com/embed/8OqoiTWrbXk

https://youtu.be/8OqoiTWrbXk

林敏夫

2014/10/07 にライブ配信

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

茶道の歴史

茶道の歴史について、各時代の人物が果たした役割を中心に、その変遷の過程を考える。

https://www.youtube.com/embed/15pyAvji88M

https://youtu.be/15pyAvji88M

林敏夫

2014/10/07 にライブ配信

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

Okakura Kakuzo – The Book of Tea #Audiobook

https://www.youtube.com/embed/4X2d30P4np8

https://youtu.be/4X2d30P4np8

Free Audiobook Collection

2018/03/16 に公開

Kakuz? OKAKURA (1862 - 1913)

The Book of Tea was written by Okakura Kakuzo in the early 20th century. It was first published in 1906, and has since been republished many times. - In the book, Kakuzo introduces the term Teaism and how Tea has affected nearly every aspect of Japanese culture, thought, and life. The book is noted to be accessibile to Western audiences because though Kakuzo was born and raised Japanese, he was trained from a young age to speak English; and would speak it all his life, becoming proficient at communicating his thoughts in the Western Mind. In his book he elucidates such topics as Zen and Taoism, but also the secular aspects of Tea and Japanese life. The book emphasises how Teaism taught the Japanese many things; most importantly, simplicity. Kakuzo argues that this tea-induced simplicity affected art and architecture, and he was a long-time student of the visual arts. He ends the book with a chapter on Tea Masters, and spends some time talking about Sen no Rikyu and his contribution to the Japanese Tea Ceremony. (Summary from Wikipedia)

Genre(s): *Non-fiction, History , Philosophy

Language: English

カテゴリ 教育

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

Reference NOTE

Okakura Kakuz?:Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okakura_Kakuz%C5%8D

Okakura Kakuz?

Okakura Kakuz? in 1898

Okakura Kakuz? (岡倉 覚三, February 14, 1862 – September 2, 1913) (also known as 岡倉 天心 Okakura Tenshin) was a Japanese scholar who contributed to the development of arts in Japan. Outside Japan, he is chiefly remembered today as the author of The Book of Tea.[1]

Born in Yokohama to parents originally from Fukui, Okakura learned English while attending a school operated by Christian missionary, Dr. Curtis Hepburn. At 15, he entered Tokyo Imperial University, where he first met and studied under Harvard-educated professor Ernest Fenollosa. In 1889, Okakura co-founded the periodical Kokka.[2] In 1887[3] he was one of the principal founders of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (東京美術学校 T?ky? Bijutsu Gakk?), and a year later became its head, although he was later ousted from the school in an administrative struggle. Later, he also founded the Japan Art Institute with Hashimoto Gah? and Yokoyama Taikan. He was invited by William Sturgis Bigelow to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 1904 and became the first head of the Asian art division in 1910.

Biography

Okakura was a high-profile urbanite who had an international sense of self. In the Meiji period he was the first dean of the Tokyo Fine Arts School (later merged with the Tokyo Music School to form the current Tokyo University of the Arts). He wrote all of his main works in English. Okakura researched Japan's traditional art and traveled to Europe, the United States, China and India. He emphasised the importance to the modern world of Asian culture, attempting to bring its influence to realms of art and literature that, in his day, were largely dominated by Western culture.[4]

His 1903 book on Asian artistic and cultural history, The Ideals of the East with Special Reference to the Art of Japan, published on the eve of the Russo-Japanese War, is famous for its opening paragraph in which he sees a spiritual unity throughout Asia, which distinguishes it from the West:

Asia is one. The Himalayas divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilisations, the Chinese with its communism of Confucius, and the Indian with its individualism of the Vedas. But not even the snowy barriers can interrupt for one moment that broad expanse of love for the Ultimate and Universal, which is the common thought-inheritance of every Asiatic race, enabling them to produce all the great religions of the world, and distinguishing them from those maritime peoples of the Mediterranean and the Baltic, who love to dwell on the Particular, and to search out the means, not the end, of life.[5]

In his subsequent book, The Awakening of Japan, published in 1904, he argued that "the glory of the West is the humiliation of Asia."[6]:107 This was an early expression of Pan-Asianism. In this book Okakura also noted that Japan's rapid modernization was not universally applauded in Asia: ″We have become so eager to identify ourselves with European civilization instead of Asiatic that our continental neighbors regard us as renegades−nay, even as an embodiment of the White Disaster itself."[6]:101

In his The Book of Tea, which was written in English in 1906, he states:

It (Teaism) insulates purity and harmony, the mystery of mutual charity, the romanticism of the social order. It is essentially a worship of the Imperfect, as it is a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know as life.

In Japan, Okakura, along with Fenollosa, is credited with "saving" Nihonga, or painting done with traditional Japanese technique, as it was threatened with replacement by Western-style painting, or "Y?ga", whose chief advocate was artist Kuroda Seiki. In fact this role, most assiduously pressed after Okakura's death by his followers, is not taken seriously by art scholars today, nor is the idea that oil painting posed any serious "threat" to traditional Japanese painting. Yet Okakura was certainly instrumental in modernizing Japanese aesthetics, having recognized the need to preserve Japan's cultural heritage, and thus was one of the major reformers during Japan's period of modernization beginning with the Meiji Restoration.

Outside Japan, Okakura influenced a number of important figures, directly or indirectly, who include Swami Vivekananda, philosopher Martin Heidegger, poet Ezra Pound, and especially poet Rabindranath Tagore and heiress Isabella Stewart Gardner, who were close personal friends of his.[7]

This page was last edited on 6 March 2018, at 16:20 (UTC).

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

Reference

千利休の生涯

http://kajipon.sakura.ne.jp/kt/haka-topic21.html

●魚問屋の息子から天下一の茶人へ

信長、秀吉という2人の天下人に仕え、茶道千家流の始祖となった“茶聖”千利休。本名は田中与四郎、号は宗易(そうえき)。大阪堺の魚問屋『ととや』に生まれる。当時の堺は貿易で栄える国際都市であり、京の都に匹敵する文化の発信地。堺は戦国期にあって大名に支配されず、商人が自治を行ない、周囲を壕で囲って浪人に警備させるという、いわば小さな独立国だった。多くの商人は同時に優れた文化人でもあった。

父は堺で高名な商人であり、利休は店の跡取りとして品位や教養を身につける為に、16歳で茶の道に入る。18歳の時に当時の茶の湯の第一人者・武野紹鴎(じょうおう)の門を叩き23歳で最初の茶会を開いた。

紹鴎の心の師は、紹鴎が生まれた年に亡くなった「侘(わ)び茶」の祖・村田珠光(じゅこう、1423-1502)。珠光は“あの”一休の弟子で、人間としての成長を茶の湯の目的とし、茶会の儀式的な形よりも、茶と向き合う者の精神を重視した。大部屋では心が落ちつかないという理由で、座敷を屏風で四畳半に囲ったことが、後の茶室へと発展していく。

紹鴎は珠光が説く「不足の美」(不完全だからこそ美しい)に禅思想を採り込み、高価な名物茶碗を盲目的に有り難がるのではなく、日常生活で使っている雑器(塩壷など)を茶会に用いて茶の湯の簡素化に努めた。そして、精神的充足を追究し、“侘び”(枯淡)を求めた。

利休は師の教えをさらに進め、“侘び”の対象を茶道具だけでなく、茶室の構造やお点前の作法など、茶会全体の様式にまで拡大した。また、当時は茶器の大半が中国・朝鮮からの輸入品であったが、利休は新たに樂茶碗など茶道具を創作し、掛物には禅の「枯淡閑寂」の精神を反映させた水墨画を選んだ。利休は“これ以上何も削れない”という極限まで無駄を削って緊張感を生み出し、村田珠光から100年を経て侘び茶を大成させた。

1568年(46歳)、活力に湧く自由都市・堺に信長が目をつける。信長は圧倒的な武力を背景に堺を直轄地にし、軍資金を差し出させ鉄砲の供給地とした。

新しいモノに目がない信長は、堺や京の町衆(町人)から強制的に茶道具の名品を買い上げ(信長の名物狩り)、武力・政治だけでなく文化の面でも覇権を目指す。信長は許可を与えた家臣にのみ茶会の開催を許し、武功の褒美に高価な茶碗を与えるなど、あらゆる面で茶の湯を利用した。

※現代でも高価な茶碗は重宝されるけど、戦国武将たちにとって名物茶器は一国一城に値するもので、その価値は今とは比較にならないものだった。名物茶釜「平蜘蛛釜」を所有していた大和の武将・松永久秀は数度にわたって信長を裏切っているにもかかわらず、信長は問答無用で攻め滅ぼすことはしなかった。1577年、信貴山城にこもった久秀を2万の織田軍で包囲した際、「もし平蜘蛛釜を差し出せば命までは奪わぬ」と降伏勧告を行った。信長が喉から手が出るほど平蜘蛛釜を欲していた事を知っていた久秀は、「信長にはワシの首も平蜘蛛釜もやらん!」と、なんと平蜘蛛釜に火薬を詰めて自分の首に縛り付け、釜もろとも爆死して天守閣を吹っ飛ばした。現代では信じられなけど、茶器が人の命を左右する時代が日本にあったんだ。(利休は43歳の時に久秀主催の茶会に茶匠として招かれている)

信長は堺とのパイプをより堅固にするべく、政財界の中心にいて茶人でもあった3人、今井宗久(そうきゅう)、津田宗及(そうぎゅう)、利休を茶頭(さどう、茶の湯の師匠)として重用した。利休は1573年(51歳)、1575年(53歳)と2度、信長主催の京都の茶会で活躍している。

信長の家臣は茶の湯に励み、ステータスとなる茶道具を欲しがった。彼らにとっての最高の栄誉は信長から茶会の許しを得ること。必然的に、茶の湯の指南役となる利休は一目置かれるようになった。

利休60歳の1582年6月1日、本能寺にて信長が自慢のコレクションを一同に披露する盛大な茶会が催された。そしてこの夜、信長は明智光秀の謀反により、多数の名茶道具と共に炎に散った。

後継者となった秀吉は、信長以上に茶の湯に熱心だった。秀吉に感化された茶の湯好きの武将は競って利休に弟子入りし、後に「利休十哲」と呼ばれる、細川三斎(ガラシアの夫)、織田有楽斎(信長の弟)、高山右近(キリシタン)、“ひょうげもの”古田織部など優れた高弟が生まれた。

1585年(63歳)、秀吉が関白就任の返礼で天皇に自ら茶をたてた禁裏茶会を利休は取り仕切り、天皇から「利休」の号を賜った(それまで宗易と名乗っていた)。このことで、その名は天下一の茶人として全国に知れ渡った。

翌年に大阪城で秀吉に謁見した大名・大友宗麟は、壁も茶器も金ピカの「黄金の茶室」で茶を服し、「秀吉に意見を言えるのは利休しかいない」と記した。

※秀吉は茶会を好んだが、いかんせん本能寺で大量の名物茶道具が焼失したこともあり、自慢できる茶器が不足していた。そこで利休は積極的に鑑定を行ない新たな「名品」を生み出していく。天下一の茶人の鑑定には絶大な信頼があり、人々は争うように利休が選んだ茶道具を欲しがるようになった。利休は自分好みの渋くストイックな茶碗を、ろくろを使用しない陶法で知られる樂長次郎ら楽焼職人に造らせた。武骨さや素朴さの中に“手びねり”ならではの温かみを持つ樂茶碗を、人々はこれまで人気があった舶来品よりも尊ぶようになり、利休の名声はさらに高まった。

1587年(65歳)、秀吉は九州を平定。実質的に天下統一を果たした祝勝と、内外への権力誇示を目的として、史上最大の茶会「北野大茶湯(おおちゃのゆ)」を北野天満宮で開催する。公家や武士だけでなく、百姓や町民も身分に関係なく参加が許されたというから、まさに国民的行事。秀吉は「茶碗1つ持ってくるだけでいい」と広く呼びかけ、利休が総合演出を担当した。当日の亭主には、利休、津田宗及、今井宗久、そして秀吉本人という4人の豪華な顔ぶれが並んだ。拝殿では秀吉秘蔵の茶道具が全て展示され、会場全域に設けられた茶席は実に800ヶ所以上となった!秀吉は満足気に各茶席を見て周り、自ら茶をたて人々にふるまったという。

★ミニコラム/利休の美学が垣間見えるエピソード集

・ある初夏の朝、利休は秀吉に「朝顔が美しいので茶会に来ませんか」と使いを出した。秀吉が“満開の朝顔の庭を眺めて茶を飲むのはさぞかし素晴らしいだろう”と楽しみにやって来ると、庭の朝顔はことごとく切り取られて全くない。ガッカリして秀吉が茶室に入ると、床の間に一輪だけ朝顔が生けてあった。一輪であるがゆえに際立つ朝顔の美しさ!秀吉は利休の美学に脱帽したという。

・秋に庭の落ち葉を掃除していた利休がきれいに掃き終わると、最後に落ち葉をパラパラと撒いた。「せっかく掃いたのになぜ」と人が尋ねると「秋の庭には少しくらい落ち葉がある方が自然でいい」と答えた。

・弟子に「茶の湯の神髄とは何ですか」と問われた時の問答(以下の答えを『利休七則』という)。「茶は服の良き様に点(た)て、炭は湯の沸く様に置き、冬は暖かに夏は涼しく、花は野の花の様に生け、刻限は早めに、降らずとも雨の用意、相客に心せよ」「師匠様、それくらいは存じています」「もしそれが十分にできましたら、私はあなたのお弟子になりましょう」。当たり前のことこそが最も難しいという利休。

・秀吉は茶の湯の権威が欲しくて「秘伝の作法」を作り、これを秀吉と利休だけが教える資格を持つとした。利休はこの作法を織田有楽斎に教えた時に、「実はこれよりもっと重要な一番の極意がある」と告げた。「是非教えて下さい」と有楽斎。利休曰く「それは自由と個性なり」。利休は秘伝などと言うもったいぶった作法は全く重要ではないと説いた。

・利休が設計した二畳敷の小さな茶室『待庵(たいあん)』(国宝)は、限界まで無駄を削ぎ落とした究極の茶室。利休が考案した入口(にじり口)は、間口が狭いうえに低位置にあり、いったん頭を下げて這うような形にならないと中に入れない。それは天下人となった秀吉も同じだ。しかも武士の魂である刀を外さねばつっかえてくぐれない。つまり、一度茶室に入れば人間の身分に上下はなく、茶室という小宇宙の中で「平等の存在」になるということだ。このように、茶の湯に関しては秀吉といえども利休に従うしかなかった。

・「世の中に茶飲む人は多けれど 茶の道を知らぬは 茶にぞ飲まるる(茶の道を知らねば茶に飲まれる)」(利休)

●秀吉との対立〜切腹へ

利休と秀吉は茶の湯の最盛期「北野大茶湯」が蜜月のピークだった。やがて徐々に両者の関係が悪化していく。秀吉は貿易の利益を独占する為に、堺に対し税を重くするなど様々な圧力を加え始め、独立の象徴だった壕(ごう)を埋めてしまう。これは信長でさえやらなかったことだ。堺の権益を守ろうとする利休を秀吉は煩わしく感じる。

1590年(68歳)、秀吉が小田原で北条氏を攻略した際に、利休の愛弟子・山上宗二が、秀吉への口の利き方が悪いとされ、その日のうちに処刑される(しかも耳と鼻を削がれて!)。衝撃を受ける利休。茶の湯に関しても、秀吉が愛したド派手な「黄金の茶室」は、利休が理想とする木と土の素朴な草庵と正反対のもの。秀吉は自分なりに茶に一家言を持っているだけに、利休との思想的対立が日を追って激しくなっていく。

←秀吉愛用の「黄金の茶室」(こんなとこ、落ち着かないと思う…)

そして翌1591年!1月13日の茶会で、派手好みの秀吉が黒を嫌うことを知りながら、「黒は古き心なり」と平然と黒楽茶碗に茶をたて秀吉に出した。他の家臣を前に、秀吉はメンツが潰れてしまう。

9日後の22日、温厚・高潔な人柄で人望を集めていた秀吉の弟・秀長が病没する。秀長は諸大名に対し「内々のことは利休が、公のことは秀長が承る」と公言するほど利休を重用していた。利休は最大の後ろ盾をなくした。

それから1ヵ月後の2月23日、利休は突然秀吉から「京都を出て堺にて自宅謹慎せよ」と命令を受ける。利休が参禅している京都大徳寺の山門を2年前に私費で修復した際に、門の上に木像の利休像を置いたことが罪に問われた(正確には利休の寄付の御礼に大徳寺側が勝手に置いた)。大徳寺の山門は秀吉もくぐっており、上から見下ろすとは無礼極まりないというのだ。秀吉は利休に赦しを請いに来させて、上下関係をハッキリ分からせようと思っていた。

秀吉の意を汲んだ家臣団のトップ・前田利家は利休のもとへ使者を送り、秀吉の妻(おね)、或いは母(大政所)を通じて詫びれば今回の件は許されるだろうと助言する。だが、利休はこれを断った。「秘伝の作法」に見られるような、権力の道具としての茶の湯は、「侘び茶」の開祖・村田珠光も、師の武野紹鴎も、絶対に否定したはず。秀吉に頭を下げるのは先輩茶人だけでなく、茶の湯そのものも侮辱することになる…。

利休には多くの門弟がいたが、秀吉の勘気に触れることを皆が恐れて、京を追放される利休を淀の船着場で見送ったのは、古田織部と細川三斎の2人だけだった。

利休が謝罪に来ず、そのまま堺へ行ってしまったことに秀吉の怒りが沸点に達した。

2月25日、利休像は山門から引き摺り下ろされ、京都一条戻橋のたもとで磔にされる。

26日、秀吉は気が治まらず、利休を堺から京都に呼び戻す。

27日、織部や三斎ら弟子たちが利休を救う為に奔走。

そして28日。この日は朝から雷が鳴り天候が荒れていた。利休のもとを訪れた秀吉の使者が伝えた伝言は「切腹せよ」。この使者は利休の首を持って帰るのが任務だった。利休は静かに口を開く「茶室にて茶の支度が出来ております」。使者に最後の茶をたてた後、利休は一呼吸ついて切腹した。享年69歳。利休の首は磔にされた木像の下に晒された。

利休の死から7年後、秀吉も病床に就き他界する。晩年の秀吉は、短気が起こした利休への仕打ちを後悔し、利休と同じ作法で食事をとったり、利休が好む枯れた茶室を建てさせたという。さらに17年後の1615年。大坂夏の陣の戦火は堺の街をも焦土と化し、豊臣家はここに滅亡した。

●後日談

利休の自刃後に高弟の古田織部が秀吉の茶頭となった。秀吉が没すると、織部は家康に命じられて2代徳川秀忠に茶の湯を指南した。だが、織部の自由奔放な茶が人気を集め始めると、家康は織部が利休のように政治的影響力を持つことを恐れるようになる。そして、大阪の陣の後に「織部は豊臣方と通じていた」として切腹を命じた。(この時代、茶をたてるのも命がけだ)

利休、織部に切腹命令が出たことは世の茶人たちを萎縮させた。徳川幕府の治世で社会に安定が求められると、利休や織部のように既成の価値観を破壊して新たな美を生み出す茶の湯は危険視され、保守的で雅な「奇麗さび」とされる小堀遠州らの穏やかなものが主流になった。

後年、利休の孫・千宗旦が家を再興する。そして宗旦の次男・宗守が『武者小路千家官休庵』を、三男・宗佐が『表千家不審庵』を、四男・宗室が『裏千家今日庵』をそれぞれ起こした。利休の茶の湯は400年後の現代まで残り、今や世界各国の千家の茶室で、多くの人がくつろぎのひと時を楽しんでいる。

※利休が公式に開いた最後の茶会の客は 家康だった(切腹の1ヶ月前)。

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

Reference NOTE

Sen no Riky?:Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sen_no_Riky%C5%AB

Sen_no_Rikyu

Sen no Riky? (千利休, 1522 – April 21, 1591), also known simply as Riky?, is considered the historical figure with the most profound influence on chanoyu, the Japanese "Way of Tea", particularly the tradition of wabi-cha. He was also the first to emphasize several key aspects of the ceremony, including rustic simplicity, directness of approach and honesty of self. Originating from the Sengoku period and the Azuchi–Momoyama period, these aspects of the tea ceremony persist.[1] Riky? is known by many names; for convenience this article will refer to him as Riky? throughout.

There are three iemoto (s?ke), or "head houses", of the Japanese Way of Tea, that are directly descended from Riky?: the Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushak?jisenke, all three of which are dedicated to passing forward the teachings of their mutual family founder, Riky?.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Later years

3 Death

4 In popular culture

5 See also

6 Notes

7 References

8 Further reading

9 External links

Early life

Riky? was born in Sakai in present-day Osaka Prefecture. His father was a warehouse owner named Tanaka Yohei (田中与兵衛), who later in life also used the family name Sen, and his mother was Gesshin My?chin (月岑妙珎).[2] His childhood name was Yoshiro.[3]

As a young man, Riky? studied tea under the townsman of Sakai named Kitamuki D?chin (1504–62),[4] and at nineteen, through D?chin's introduction, he began to study tea under Takeno J??, who is also associated with the development of the wabi aesthetic in tea ceremony. He is believed to have received the Buddhist name S?eki (宗易) from the Rinzai Zen priest Dairin S?t? (1480–1568) of Nansh?ji temple in Sakai.[5] He married a woman known as H?shin My?ju (d. 1577) around when he was twenty-one.[6] Riky? also underwent Zen training at Daitoku-ji temple in Kyoto. Not much is known about his middle years.

Later years

In 1579, at the age of 58, Riky? became a tea master for Oda Nobunaga[7] and, following Nobunaga's death in 1582, he was a tea master for Toyotomi Hideyoshi.[8] His relationship with Hideyoshi quickly deepened, and he entered Hideyoshi's circle of confidants, effectively becoming the most influential figure in the world of chanoyu.[9] In 1585, because he needed extra credentials in order to enter the Imperial Palace so that he could help at a tea gathering that would be given by Hideyoshi for Emperor ?gimachi and held at the Imperial Palace, the emperor bestowed upon him the Buddhist lay name and title "Riky? Koji" (利休居士).[10] Another major chanoyu event of Hideyoshi's that Riky? played a central role in was the Grand Kitano Tea Ceremony, held by Hideyoshi at the Kitano Tenman-g? in 1587.

His chashitsu Tai-an at the My?ki-an, Kyoto

Suigetsu (Intoxicated by the Moon) paper hanging scroll for a tea ceremony by Sen no Riky?, c. 1575

Flower vase Onkyoku, by Sen no Riky?, 16th century

It was during his later years that Riky? began to use very tiny, rustic tea rooms referred as s?-an ("grass hermitage"), such as the two-tatami mat tea room named Tai-an, which can be seen today at My?ki-an temple in Yamazaki, a suburb of Kyoto, and which is credited to his design. This tea room has been designated as a National Treasure. He also developed many implements for tea ceremony, including flower containers, teascoops, and lid rests made of bamboo, and also used everyday objects for tea ceremony, often in novel ways.

Raku teabowls were originated through his collaboration with a tile-maker named Raku Ch?jir?. Riky? had a preference for simple, rustic items made in Japan, rather than the expensive Chinese-made items that were fashionable at the time. Though not the inventor of the philosophy of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in the very simple, Riky? is among those most responsible for popularizing it, developing it, and incorporating it into tea ceremony. He created a new form of tea ceremony using very simple instruments and surroundings. This and his other beliefs and teachings came to be known as s?an-cha (the grass-thatched hermitage style of chanoyu), or more generally, wabi-cha. This line of chanoyu that his descendants and followers carried on was recognized as the Senke-ry? (千家流, "school of the house of Sen").

A writer and poet, the tea master referred to the ware and its relationship with the tea ceremony, saying, "Though you wipe your hands and brush off the dust and dirt from the vessels, what is the use of all this fuss if the heart is still impure?"[11]

Two of his primary disciples were Nanb? S?kei (南坊宗啓; dates unknown), a somewhat legendary Zen priest; and Yamanoue S?ji (1544–90), a townsman of Sakai. Nanb? is credited as the original author of the Nanp? roku, a record of Riky?'s teachings. Yamanoue's chronicle, the Yamanoue S?ji ki (山上宗二記), gives commentary about Riky?'s teachings and the state of chanoyu at the time of its writing.[12]

Riky? had a number of children, including a son known in history as Sen D?an, and daughter known as Okame. This daughter became the bride of Riky?'s second wife's son by a previous marriage, known in history as Sen Sh?an. Due to many complex circumstances, Sen Sh?an, rather than Riky?'s legitimate heir, D?an, became the person counted as the 2nd generation in the Sen-family's tradition of chanoyu (see "san-Senke" at schools of Japanese tea ceremony).

Riky? also wrote poetry, and practiced ikebana.

One of his favourite gardens was said to be at Chishaku-in in Kyoto.[13]

This page was last edited on 12 September 2018, at 13:49 (UTC).

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

Reference

OGIN SAMA

https://www.youtube.com/embed/gEEsvsZ6sF4

https://youtu.be/gEEsvsZ6sF4

Jesus Cortes

2015/12/03 に公開

"Ogin-sama". Tanaka Kinuyo. 1962 (VOSE)

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

Reference

お吟さま – Ogin-sama - Love Under the Crucifix (1962) Kinuyo Tanaka

https://www.youtube.com/embed/JRA9fqN-SXE

https://youtu.be/JRA9fqN-SXE

Golden Retriever

2018/09/03 に公開

1h 42min | Drama | 3 June 1962 (Japan)

The basic story in Love under the Crucifix is about Ogin, daughter of a tea master, who are both Christians in feudal Japan. Ogin falls in love with a feudal prince, also a Christian who is already married, and that creates problems. Further, when the Shogun bans Christianity, the situation worsens.

Kinuyo Tanaka was a Japanese actress and director. She had a career lasting over 50 years with more than 250 credited films, and was best known for her roles in collaboration with director Kenji Mizoguchi over 15 films between 1940 and 1954

カテゴリ 映画とアニメ

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

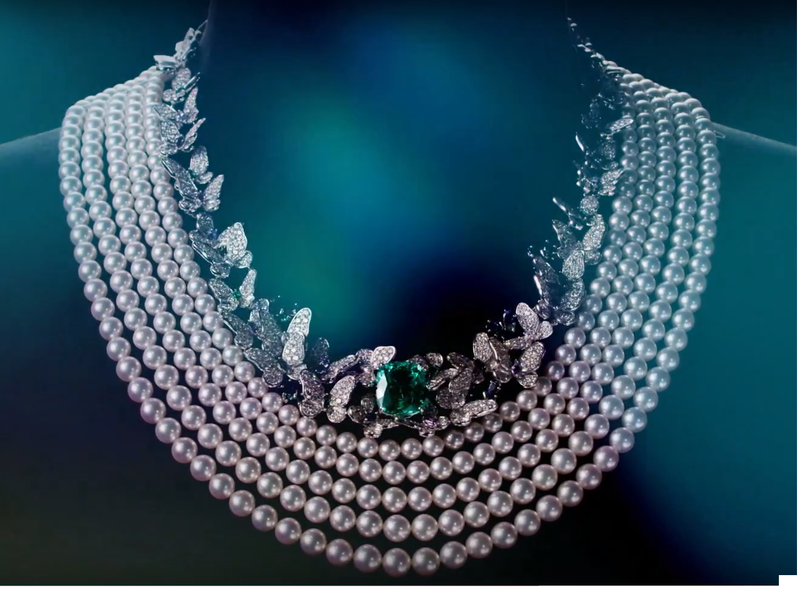

MIKIMOTO - "Praise to Nature" Three butterflies

MIKIMOTO - "Praise to Nature" Three butterflies

https://www.mikimoto.com/en/high/detail22.html

https://youtu.be/SPF8dNvkOk0

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

"MIKIMOTO Teaser - September 2017 "Praise to Nature"

"MIKIMOTO Teaser - September 2017 "Praise to Nature"

https://youtu.be/DhWhEB8Xy-g

https://www.youtube.com/embed/DhWhEB8Xy-g

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

"MIKIMOTO - "Praise to Nature" Bouquets of the four seasons"

"MIKIMOTO - "Praise to Nature" Bouquets of the four seasons"

https://www.mikimoto.com/en/high/praisetonature.html

☆☆☆============☆☆☆ ◇◇◇ ☆☆☆============☆☆☆

☆☆☆==============================================☆☆☆

☆☆☆==============================================☆☆☆

広告

☆☆☆==============================================☆☆☆

広告

☆===================================================☆

広告

☆===================================================☆

広告

☆☆☆==============================================☆☆☆

広告 Google Ad

☆===================================================☆

広告 Google Ad

☆===================================================☆

広告 Google Ad

☆===================================================☆

広告

広告

☆===================================================☆

広告

☆===================================================☆

広告

☆===================================================☆

広告

☆☆☆=========================================================☆☆☆

☆☆☆=========================================================☆☆☆