PR

X

Keyword Search

▼キーワード検索

Comments

続日本100名城東北の…

New!

オジン0523さん

【甥のステント挿入… New!

Gママさん

New!

Gママさん

2025年版・岡山大学… New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

ムベの実を開くコツ… noahnoahnoahさん

noahnoahnoahさん

エコハウスにようこそ ecologicianさん

【甥のステント挿入…

New!

Gママさん

New!

Gママさん2025年版・岡山大学…

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

New!

隠居人はせじぃさんムベの実を開くコツ…

noahnoahnoahさん

noahnoahnoahさんエコハウスにようこそ ecologicianさん

Calendar

カテゴリ: 海外旅行

9世紀後半〜20世紀初頭の服装の女性が望遠鏡を操作している線画。

「アイルランド出身女性科学者が宇宙の解明に貢献した」と。

中心に明るいバルジ(膨らみ)を持ち、そこから渦を巻くように腕が広がっている。

これは典型的な渦巻銀河の構造。

宇宙空間に無数の岩石が浮かぶ小惑星帯(asteroid belt)の写真か?

そして次の展示は アイルランド系の著名な子孫たちを紹介するセクション。

「 アイルランド人の「世界への影響」の多様性(科学・政治・芸術など) 。」

この展示は、 ベルナルド・オイギンス(Bernardo O’Higgins)

彼は、 アイルランド系移民の子孫 として南米で活躍した代表的な歴史人物の一人。

ロナルド・レーガン(Ronald Reagan) 。

「アイルランド出身女性科学者が宇宙の解明に貢献した」と。

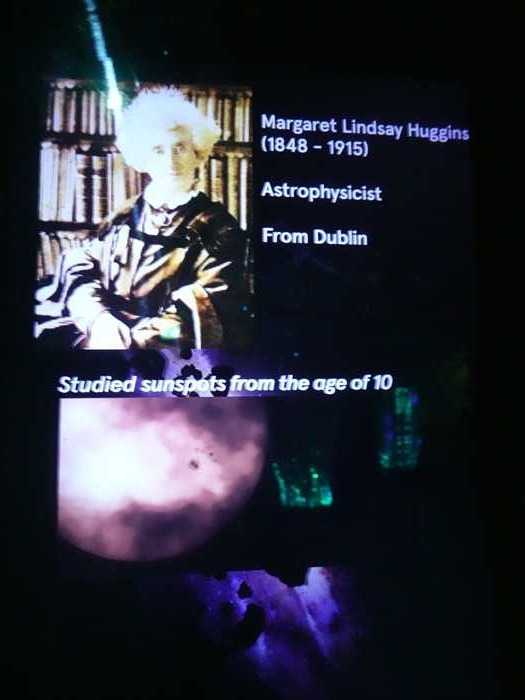

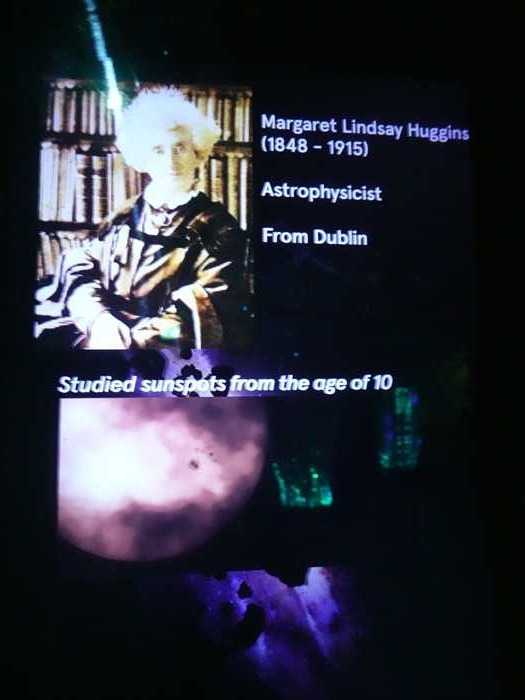

Margaret Lindsay Huggins(マーガレット・リンジー・ハギンズ)

生没年

:1848–1915

職業

:Astrophysicist(天体物理学者)

出身地

:ダブリン(Dublin)

「Studied sunspots from the age of 10」

【10歳から黒点(sunspots)の研究を始めた】

画面下部には、黒点を映した太陽像の写真が表示されていた。

「Studied sunspots from the age of 10」

【10歳から黒点(sunspots)の研究を始めた】

画面下部には、黒点を映した太陽像の写真が表示されていた。

主な業績:

・恒星や星雲のスペクトル写真撮影の先駆者。

・夫と共に星の化学組成や運動を分析し、天体の物理的理解に貢献。

・19世紀末の科学界において女性が主導的に活動した稀有な存在。

中心に明るいバルジ(膨らみ)を持ち、そこから渦を巻くように腕が広がっている。

これは典型的な渦巻銀河の構造。

宇宙空間に無数の岩石が浮かぶ小惑星帯(asteroid belt)の写真か?

小惑星帯とは?

・主に火星と木星の間に位置する帯状の領域。

・太陽系形成時に惑星になり損ねた物質が残ったとされる。

・代表的な天体:ケレス(準惑星)、ベスタ、パラスなど。

この画像は、EPIC博物館における「アイルランド人の宇宙への貢献」を讃える展示の一部で、

銀河→太陽→黒点→小惑星という宇宙スケールの旅を視覚的に展開しているのであった。

この画像は、EPIC博物館における「アイルランド人の宇宙への貢献」を讃える展示の一部で、

銀河→太陽→黒点→小惑星という宇宙スケールの旅を視覚的に展開しているのであった。

そして次の展示は アイルランド系の著名な子孫たちを紹介するセクション。

「 アイルランド人の「世界への影響」の多様性(科学・政治・芸術など) 。」

この展示は、 ベルナルド・オイギンス(Bernardo O’Higgins)

彼は、 アイルランド系移民の子孫 として南米で活躍した代表的な歴史人物の一人。

・ 生没年:

1778年 ~ 1842年

・ 出身地:

チリ(父親はアイルランド出身のアンブロシオ・オイギンス)

・ 功績:

・ チリ独立の父と呼ばれる

。

・スペインからの独立戦争を指導し、 初代チリ共和国の最高指導者(Supreme Director)

に就任。

に就任。

・独立後、 奴隷制の廃止や土地改革、教育制度の充実

などを推進。

右上には 第40代アメリカ合衆国大統領・ロナルド・レーガン(Ronald Reagan) の姿が。

右上には 第40代アメリカ合衆国大統領・ロナルド・レーガン(Ronald Reagan) の姿が。

ロナルド・レーガン(Ronald Reagan) 。

・生没年:1911年~2004年

・ 第40代アメリカ合衆国大統領(任期:1981年~1989年)

・ 元ハリウッド俳優・カリフォルニア州知事を経て大統領に就任。

・「レーガノミクス」やソ連との冷戦終結に向けた強硬外交などで知られる。

・ Great-Grandfather from Tipperary

・ Great-Grandfather from Tipperary

→ 曽祖父がアイルランド・ティペラリー県の出身

と。

展示パネル

・上段:アメリカ国旗を背景にした大統領演説中の写真

・中央左:「Ronald Reagan」の文字とスピーチ用マイク(演説シーン)

・中央右:共和党全国大会(風船や拍手のシーン)

・下段左:星条旗に囲まれた演説会場の映像

・下段右:アイルランド国旗が並ぶ演壇に立つレーガン(アイルランド訪問時)

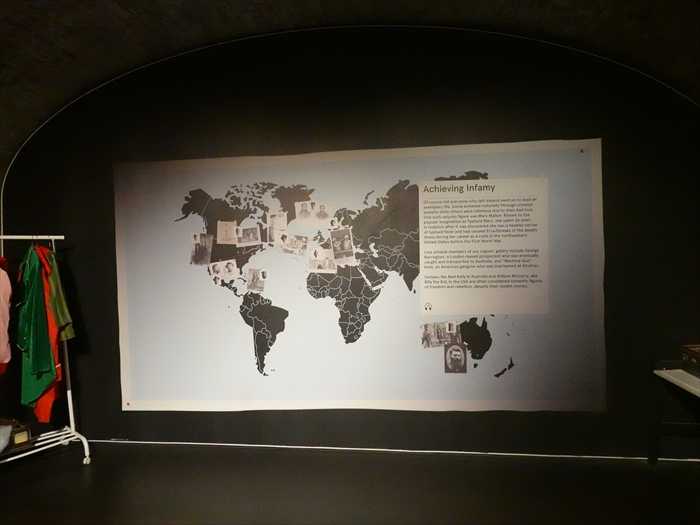

「 Meet the Notorious Irish(悪名高きアイルランド人たち) 」

このセクションは、歴史的に「悪名高い」「一癖ある」と言われたアイルランド系移民や

その子孫たちを紹介するコーナー。

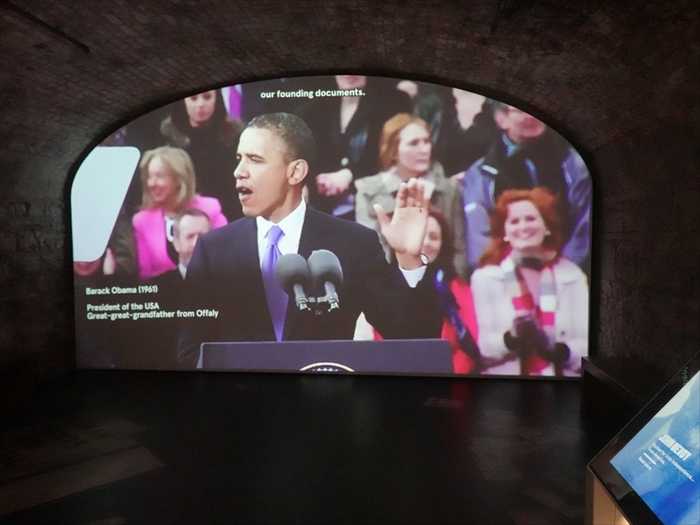

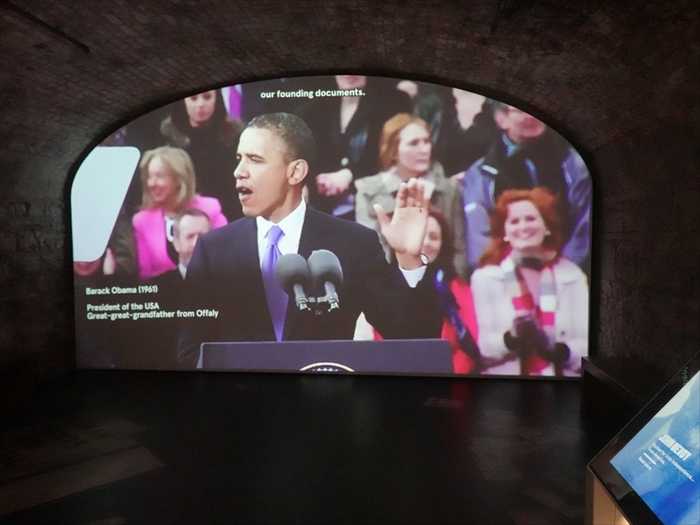

バラク・オバマ(Barack Obama)

に関するもの。

アイルランド移民の血筋が、アメリカの最高権力者にまでつながっている と。

アイルランド移民の血筋が、アメリカの最高権力者にまでつながっている と。

アイルランド系の血筋を持つ世界的リーダーを紹介する中で、彼もその一人として

取り上げられていた。

取り上げられていた。

バラク・オバマ(Barack Obama)

・生年:1961年

・ 第44代アメリカ合衆国大統領(2009年〜2017年)

・ アメリカ初のアフリカ系大統領として歴史に名を刻んだ人物

。

・ オバマの母方の先祖にあたるFulmuth Kearney(1830年生まれ)がアイルランドの

County Offaly(オファリー県)Moneygall村の出身。

・ オバマの母方の先祖にあたるFulmuth Kearney(1830年生まれ)がアイルランドの

County Offaly(オファリー県)Moneygall村の出身。

・ 1850年ごろ、アメリカに移民として渡った。

「 Meet the Notorious Irish(悪名高きアイルランド人たち) 」

このセクションは、歴史的に「悪名高い」「一癖ある」と言われたアイルランド系移民や

その子孫たちを紹介するコーナー。

「Notorious(ノートリアス)」という語は…

・単なる「悪人」ではなく、

・社会的に注目され、物議を醸した、あるいは型破りな人物、

・あるいは「犯罪的な側面を持ちながらも魅力的・伝説的」な人物を含むのだ と。

「アイルランド人の移民が世界で果たした多様な役割」をあらゆる角度から紹介

。

・「英雄」だけでなく、

・「悪党・革命家・流れ者・海賊」なども含め、

・アイルランド人のグローバルな影響力の広がりを示していたのであった。

「 Meet the Notorious Irish(悪名高きアイルランド人たち)

」セクションの壁面パネル

(新聞見出し風)展示

(新聞見出し風)展示

このセクションでは、「 アイルランド人の移民は、時に社会の周縁や地下世界でも存在感を示した

」

という歴史の一面を、ユーモラスかつ皮肉を込めて伝えていたのであった。

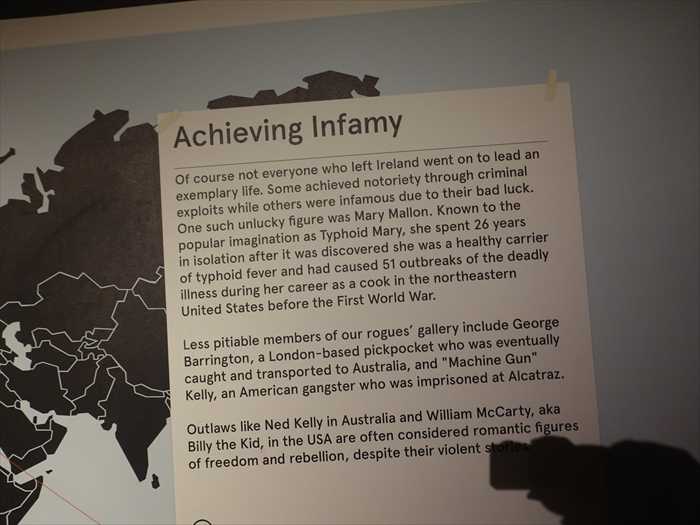

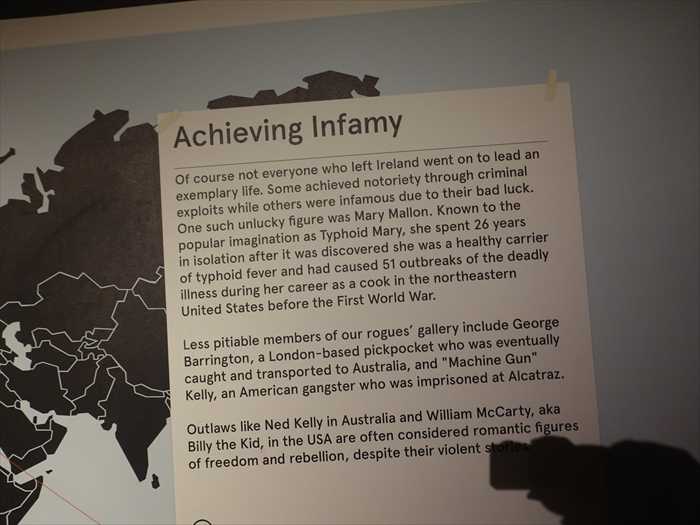

「 Achieving Infamy(悪名を馳せた人々) 」セクションの締めくくりを象徴する展示。

「Achieving Infamy

Of course not everyone who left Ireland went on to lead an exemplary life. Some

achieved notoriety through criminal exploits while others were infamous due to

their bad luck.One such unlucky figure was Mary Mallon. Known to the popular

imagination as Typhoid Mary, she spent 26 years in isolation after it was discovered

she was a healthy carrier of typhoid fever and had caused 51 outbreaks of the deadly

illness during her career as a cook in the northeastern United States before

the First World War.Less pitiable members of our rogues' gallery include George Barrington, a London-based pickpocket who was eventually caught and transported to Australia, and "Machine Gun"

Kelly, an American gangster who was imprisoned at Alcatraz.

Outlaws like Ned Kelly in Australia and William McCarty, aka Billy the Kid, in the USA

are often considered romantic figures of freedom and rebellion, despite their

violent stories.」

【 悪名を馳せた人々

より同情の余地が少ない「悪名高きギャラリー」の面々には、ロンドンを拠点としたスリの

ジョージ・バリントン(後に逮捕されオーストラリアへ流刑)や、「マシンガン」ケリー

(アルカトラズ刑務所に収監されたアメリカのギャング)などがいます。

また、オーストラリアのネッド・ケリーやアメリカのビリー・ザ・キッド

(本名:ウィリアム・マッカーティ)のような無法者たちは、暴力的な背景を持ちながらも、

自由と反抗のロマン的象徴とされることが多いのです。】

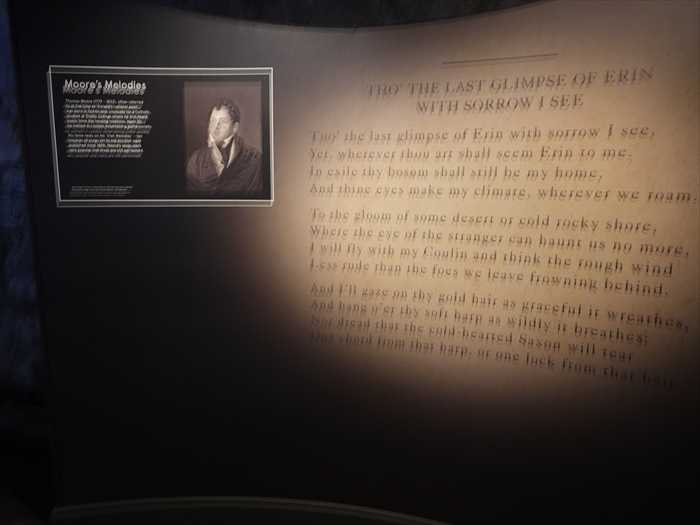

次は「 アイルランド音楽と詩の伝統 」を象徴する展示の一つで、

トマス・ムーア(Thomas Moore)とその名作「Moore’s Melodies(ムーアの旋律)」 に

焦点を当てていた。

「Moore’s Melodies

「 Achieving Infamy(悪名を馳せた人々) 」セクションの締めくくりを象徴する展示。

「Achieving Infamy

Of course not everyone who left Ireland went on to lead an exemplary life. Some

achieved notoriety through criminal exploits while others were infamous due to

their bad luck.One such unlucky figure was Mary Mallon. Known to the popular

imagination as Typhoid Mary, she spent 26 years in isolation after it was discovered

she was a healthy carrier of typhoid fever and had caused 51 outbreaks of the deadly

illness during her career as a cook in the northeastern United States before

the First World War.Less pitiable members of our rogues' gallery include George Barrington, a London-based pickpocket who was eventually caught and transported to Australia, and "Machine Gun"

Kelly, an American gangster who was imprisoned at Alcatraz.

Outlaws like Ned Kelly in Australia and William McCarty, aka Billy the Kid, in the USA

are often considered romantic figures of freedom and rebellion, despite their

violent stories.」

【 悪名を馳せた人々

もちろん、アイルランドを離れた人すべてが模範的な人生を歩んだわけではありません。

中には犯罪行為によって悪名を馳せた者もいれば、不運によって知られることになった人もいます。

中には犯罪行為によって悪名を馳せた者もいれば、不運によって知られることになった人もいます。

そのような不運な人物の一人がメアリー・マロン(Mary Mallon)です。「腸チフスの

メアリー(Typhoid Mary)」として広く知られ、第一次世界大戦前にアメリカ北東部で料理人

として働いていた際に腸チフスの健康保菌者であり、この致命的な病気の流行を 51 回も

引き起こしたことが判明した後、 26 年間も隔離生活を送りました。

メアリー(Typhoid Mary)」として広く知られ、第一次世界大戦前にアメリカ北東部で料理人

として働いていた際に腸チフスの健康保菌者であり、この致命的な病気の流行を 51 回も

引き起こしたことが判明した後、 26 年間も隔離生活を送りました。

より同情の余地が少ない「悪名高きギャラリー」の面々には、ロンドンを拠点としたスリの

ジョージ・バリントン(後に逮捕されオーストラリアへ流刑)や、「マシンガン」ケリー

(アルカトラズ刑務所に収監されたアメリカのギャング)などがいます。

(本名:ウィリアム・マッカーティ)のような無法者たちは、暴力的な背景を持ちながらも、

自由と反抗のロマン的象徴とされることが多いのです。】

この文章は、EPIC博物館の「 移民の物語は栄光だけではなく、影の部分もある

」 というテーマ

を

表現する核心メッセージ。

特に:

表現する核心メッセージ。

特に:

・無法者(outlaw)と英雄のあいだの曖昧さ

・不運と誤解によって悪名を得た人物(例:タイフォイド・メアリー)

・移民の苦しみと社会からの排除

といった現代的にも共鳴するテーマが、展示を通して伝わって来たのであった。

この展示パネルは、 アイルランド移民によって世界に広がった音楽とダンスの伝統

について紹介。

「 Music and Dance: Sharing the Tradition

The Irish love of a tune travelled with them when they left in search of a better life.

The Irish love of a tune travelled with them when they left in search of a better life.

The mass emigration of famine times in the mid-19th century saw the music and

dance of Ireland carried to Britain and America. In time, some of these forms were

adapted and became part of popular entertainment on the American stage.

The early 20th century arrival of new technologies – sound recording, radio and cinema – brought Irish talent to even bigger audiences.」

【 音楽とダンス:伝統を分かち合う

dance of Ireland carried to Britain and America. In time, some of these forms were

adapted and became part of popular entertainment on the American stage.

The early 20th century arrival of new technologies – sound recording, radio and cinema – brought Irish talent to even bigger audiences.」

【 音楽とダンス:伝統を分かち合う

アイルランド人の音楽への愛は、彼らがより良い生活を求めて旅立つときにも、常に共に

ありました。19世紀半ばの飢饉時代の大量移民により、アイルランドの音楽とダンスは

イギリスやアメリカへと運ばれました。やがてその一部は形を変え、アメリカの舞台芸術の

一部として定着していきます。

ありました。19世紀半ばの飢饉時代の大量移民により、アイルランドの音楽とダンスは

イギリスやアメリカへと運ばれました。やがてその一部は形を変え、アメリカの舞台芸術の

一部として定着していきます。

20世紀初頭には、録音技術・ラジオ・映画といった新たな技術の登場により、アイルランドの

才能はさらに多くの観客へと届くようになりました。】

才能はさらに多くの観客へと届くようになりました。】

この展示コーナーが伝えているポイントは:

・アイルランド移民は文化(特に音楽・ダンス)を持って旅立った。

・それは新天地(特にアメリカ)で融合・進化し、ミュージカル・ショー・映画などへ。

・テクノロジーの力で、その伝統が大衆娯楽の主流に躍り出た。

代表的な例には:

・アイリッシュ・ダンス → 「リバーダンス」などに発展

・ケルト音楽 → カントリー音楽やフォークのルーツの一部に

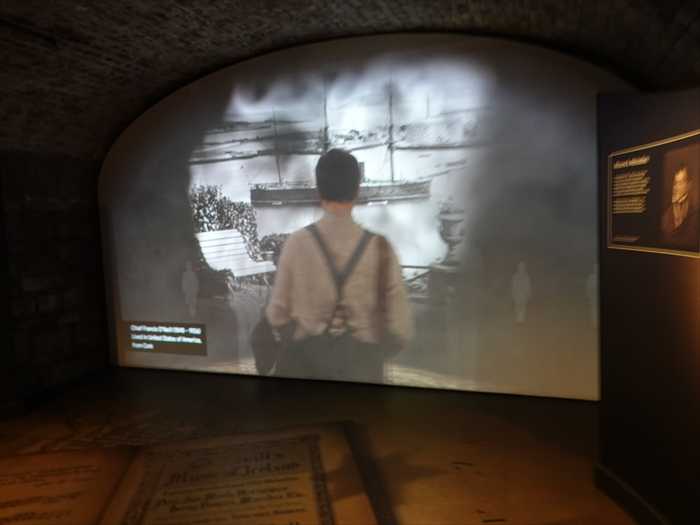

「移民の旅立ち(The Departure)」 を表現した映像演出の場面。

「移民の旅立ち(The Departure)」 を表現した映像演出の場面。

・ 飢饉、貧困、抑圧から逃れるために、多くのアイルランド人が19世紀〜20世紀にかけて

海外へ移住 。

海外へ移住 。

・ 多くはアメリカ、カナダ、オーストラリア、イギリス

へ。

・この映像は、 その瞬間の「不安」「希望」「哀愁」を象徴的に描いたもの

。

次は「 アイルランド音楽と詩の伝統 」を象徴する展示の一つで、

トマス・ムーア(Thomas Moore)とその名作「Moore’s Melodies(ムーアの旋律)」 に

焦点を当てていた。

「Moore’s Melodies

Thomas Moore’s collection of Irish Melodies, published between 1808 and 1834,

was extremely popular among Irish emigrants in the 19th century.

was extremely popular among Irish emigrants in the 19th century.

His lyrics, which were often sentimental and patriotic, were set to traditional Irish tunes,

and they helped preserve a sense of Irish identity abroad.

and they helped preserve a sense of Irish identity abroad.

The melodies were shared in songbooks and performed in drawing rooms and

public halls across Britain, America, and beyond.」

【 ムーアの旋律

public halls across Britain, America, and beyond.」

【 ムーアの旋律

トマス・ムーアの『アイルランド旋律集』は、1808年から1834年にかけて発表され、

19世紀のアイルランド移民たちの間で非常に人気を博しました。

19世紀のアイルランド移民たちの間で非常に人気を博しました。

彼の歌詞は、しばしばセンチメンタルで愛国的なものであり、伝統的なアイルランド民謡に

合わせて書かれていました。

合わせて書かれていました。

これらの旋律は、国外におけるアイルランド人のアイデンティティの保持に大きく貢献しました。

楽譜は歌集として配布され、英国・アメリカなどの社交室や公会堂で歌われました。】

アイルランド系移民コミュニティの集団写真を大型パネルで再現 。

「移民と社交文化(とくにダンスホール)」に焦点を当てたもので、アイルランド系移民が

新天地で人と出会い、繋がり、未来を築いていった様子を描いている と。

「 Meet on the Dance Floor

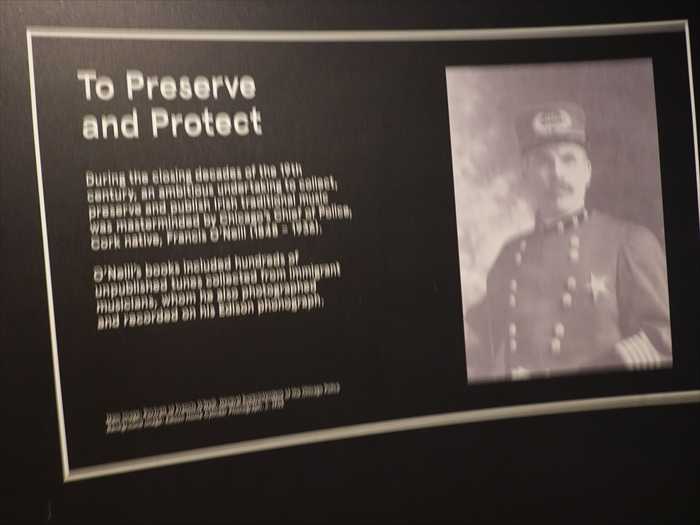

「音楽と文化の保存」に関する展示の一部で、 フランシス・オニール(Francis O’Neill)

という人物に焦点を当てていた。

「 To Preserve and Protect

という人物に焦点を当てていた。

「 To Preserve and Protect

During the closing decades of the 19th century, an ambitious undertaking to collect,

preserve and publish Irish traditional music was masterminded by a Chicago Chief of

Police, Cork native, Francis O'Neill (1848–1936).

preserve and publish Irish traditional music was masterminded by a Chicago Chief of

Police, Cork native, Francis O'Neill (1848–1936).

O'Neill's books included hundreds of unpublished tunes collected from immigrant

musicians, whom he also photographed and recorded on his Edison phonograph.」

【 保存し、守るために

musicians, whom he also photographed and recorded on his Edison phonograph.」

【 保存し、守るために

19世紀末、アイルランドの伝統音楽を収集・保存・出版する壮大な試みが行われました。

その中心人物となったのは、アメリカ・シカゴの警察署長であり、コーク出身のフランシス・

オニール(1848–1936)です。

オニールの著作には、移民音楽家から収集された未出版の楽曲が数百曲以上収められており、

彼は彼らを写真に撮影し、エジソンの蓄音機で録音することも行っていました。】

この展示は、「移民が新天地で文化を失うどころか、それを保存・記録・継承しようとした」

事例のひとつとして、オニールの活動を紹介しているのであった。

その中心人物となったのは、アメリカ・シカゴの警察署長であり、コーク出身のフランシス・

オニール(1848–1936)です。

オニールの著作には、移民音楽家から収集された未出版の楽曲が数百曲以上収められており、

彼は彼らを写真に撮影し、エジソンの蓄音機で録音することも行っていました。】

この展示は、「移民が新天地で文化を失うどころか、それを保存・記録・継承しようとした」

事例のひとつとして、オニールの活動を紹介しているのであった。

「アイルランド移民と音楽録音産業の関わり」を示すセクションの一部であり、1920年代の

アイリッシュ・ミュージック黄金時代 に焦点 を当てています。

「The Record Business

At the moment when the record business became a commercial reality, a number of

exceptionally talented Irish immigrant musicians were in New York, the centre of

the music business.

アイリッシュ・ミュージック黄金時代 に焦点 を当てています。

「The Record Business

At the moment when the record business became a commercial reality, a number of

exceptionally talented Irish immigrant musicians were in New York, the centre of

the music business.

Ellen O’Byrne De Witt, who founded an Irish music shop in New York, saw the

potential for quality recordings and her foresight helped create the "Golden Age" of

Irish music recording in the 1920s.」

【 レコード産業

potential for quality recordings and her foresight helped create the "Golden Age" of

Irish music recording in the 1920s.」

【 レコード産業

レコード産業が商業的現実となったその瞬間、数多くの優れたアイルランド系移民音楽家たちが、

音楽産業の中心地であるニューヨークに集まっていました。

音楽産業の中心地であるニューヨークに集まっていました。

エレン・オバーン・デ・ウィット(Ellen O’Byrne De Witt)は、ニューヨークでアイリッシュ・

ミュージックの専門店を開いた人物であり、良質な録音の可能性を見出した先見の明により、

1920年代の「アイリッシュ音楽録音黄金時代」を築く上で重要な役割を果たしました。】

ミュージックの専門店を開いた人物であり、良質な録音の可能性を見出した先見の明により、

1920年代の「アイリッシュ音楽録音黄金時代」を築く上で重要な役割を果たしました。】

Ellen O’Byrne De Witt とは?

・アイルランド系移民女性。

・ニューヨークに音楽ショップを開き、演奏家とレコード会社をつなぐ存在に。

・彼女の推進によって、伝統音楽が商業的に録音・流通されるきっかけが生まれました。

・その結果、1920年代のアイリッシュ・ミュージック・レコーディングの黄金期が到来。

アイルランド系移民コミュニティの集団写真を大型パネルで再現 。

「つながり、団結するアイルランド系移民」を象徴する目的で展示。

海外に渡ったアイルランド人が、新天地でもコミュニティを築き、アイデンティティを保った

ことを示すもの。

ことを示すもの。

写真に写る 人々の数と密度が、結束力の強さと人数の多さ(移民の規模)を視覚的に訴えて

いる のであった。

いる のであった。

「移民と社交文化(とくにダンスホール)」に焦点を当てたもので、アイルランド系移民が

新天地で人と出会い、繋がり、未来を築いていった様子を描いている と。

「 Meet on the Dance Floor

Irish societies, county clubs and dancehalls, filled with familiar accents and a home

from home atmosphere, were important meeting places for immigrants in American

cities. It was common for a newly-arrived immigrant to be introduced at such

gatherings to those Irish already established. Sometimes the new arrival had a job

before the evening was over.

from home atmosphere, were important meeting places for immigrants in American

cities. It was common for a newly-arrived immigrant to be introduced at such

gatherings to those Irish already established. Sometimes the new arrival had a job

before the evening was over.

There were 27 dancehalls in greater New York during the 1920s providing steady

work for immigrant musicians, as well a meeting place for young men and women.

Introductions on the dance floor often led to marriage.」

【 ダンスフロアで出会う

work for immigrant musicians, as well a meeting place for young men and women.

Introductions on the dance floor often led to marriage.」

【 ダンスフロアで出会う

アイルランド系の社交団体、郡人会、ダンスホールは、馴染みあるアクセントと言葉、そして

「故郷のような雰囲気」に満ちた空間であり、アメリカ都市部における移民たちの重要な

出会いの場でした。

「故郷のような雰囲気」に満ちた空間であり、アメリカ都市部における移民たちの重要な

出会いの場でした。

新しく到着した移民が、こうした集まりですでに定住している同郷のアイルランド人に

紹介されることはごく一般的でした。時には、その夜のうちに仕事が見つかることさえ

あったのです。

紹介されることはごく一般的でした。時には、その夜のうちに仕事が見つかることさえ

あったのです。

1920年代のニューヨーク大都市圏には、27のダンスホールがあり、移民音楽家にとって

安定した仕事の場であると同時に、若者たちが出会う場所でもありました。

安定した仕事の場であると同時に、若者たちが出会う場所でもありました。

ダンスフロアでの紹介が結婚に至ることも珍しくありませんでした。】

「アイルランド系音楽家と録音文化」に関する展示の一部で、ウィリアム・マラリー

(William Mullaly)とジェームズ・モリソン(James Morrison)という2人の伝説的音楽家を

紹介しています。金色の蓄音機(グラモフォン)ホーンの演出が、録音技術の歴史的雰囲気を

際立たせています。

「アイルランド系音楽家と録音文化」に関する展示の一部で、ウィリアム・マラリー

(William Mullaly)とジェームズ・モリソン(James Morrison)という2人の伝説的音楽家を

紹介しています。金色の蓄音機(グラモフォン)ホーンの演出が、録音技術の歴史的雰囲気を

際立たせています。

この展示は、以下のようなメッセージを伝えています:

・「録音技術の発展」がアイルランド伝統音楽の保存と普及を可能にした

・アイルランドからの移民たちは、単に演奏者であるだけでなく、文化の継承者・記録者でもあった

・彼らの録音は、100年以上たった今でも再生可能であり、文化遺産として残っている

「 WILLIAM MULLALY(ウィリアム・マラリー)

・楽器:コンサーティーナ(Concertina)

・活動時期:主に1920年代

・意義:

・アイルランド伝統音楽の演奏家としては、最初期に録音されたコンサーティーナ奏者の

一人。

一人。

・コンサーティーナという比較的マイナーな楽器を、録音・商業流通という形で残すことに

成功。

成功。

・移民先のアメリカで録音されたレコードが、母国アイルランドにも逆輸入される形で

知られる。」

「 JAMES MORRISON(ジェームズ・モリソン)

知られる。」

「 JAMES MORRISON(ジェームズ・モリソン)

・楽器:フィドル(バイオリン)

・生年:1893年(スライゴー県出身)

・活動拠点:アメリカ・ニューヨーク

・意義:

・1920年代〜30年代にかけて、アイルランド伝統フィドルの最重要人物の一人。

・同時代のマイケル・コールマン(Michael Coleman)と並び称される。

・自身のバンドを率いて多くの録音を残し、アメリカ移民社会でアイルランド音楽の象徴的存在

となった。」

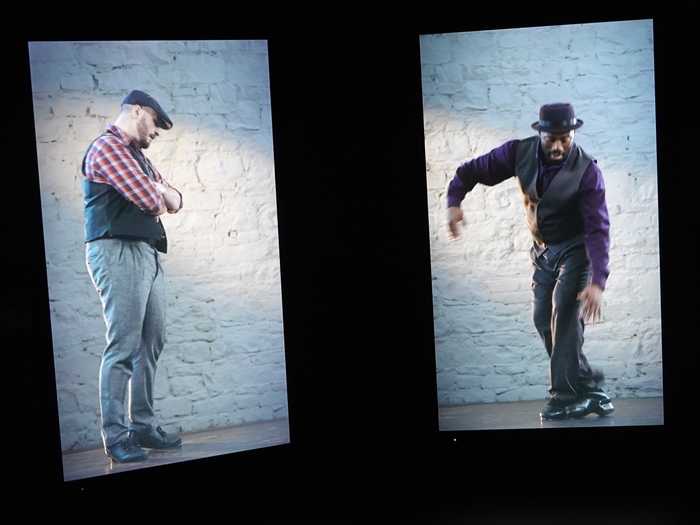

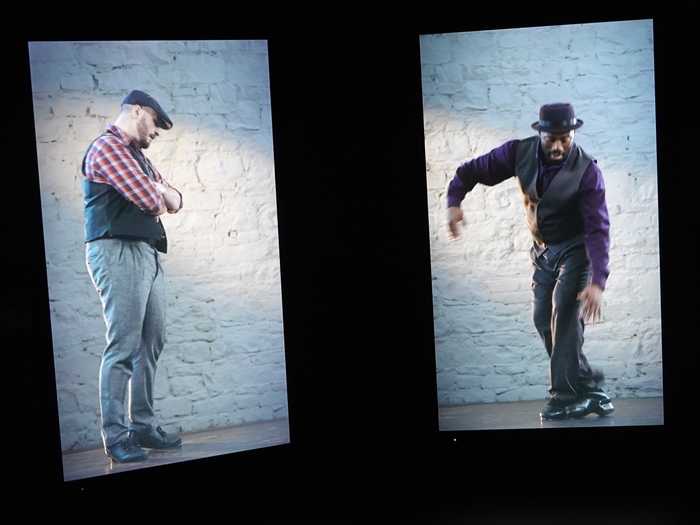

アイリッシュ・ステップダンスとアメリカのタップダンスの融合と影響 を視覚的に表現した

ビデオ・インスタレーションの一場面.

「 From Folk to Country

となった。」

アイリッシュ・ステップダンスとアメリカのタップダンスの融合と影響 を視覚的に表現した

ビデオ・インスタレーションの一場面.

「 From Folk to Country

Irish music had a considerable influence on the development of music in the United States.

The music skills brought by Irish and other immigrant groups combined with existing

forms to create American folk music.

The music skills brought by Irish and other immigrant groups combined with existing

forms to create American folk music.

Fiddle players with their repertoire of dance tunes – particularly lively reels and hornpipes

– seem to have made the biggest impression. Uilleann pipers were also heard in different American settings but their uniquely Irish sound limited their appeal. The transition from

the fiddle neck to the finger board of the banjo – an instrument of Afro-American origin –

was not difficult for a musician to make and this allowed many fiddlers to adapt to the

banjo's rise in popularity.

– seem to have made the biggest impression. Uilleann pipers were also heard in different American settings but their uniquely Irish sound limited their appeal. The transition from

the fiddle neck to the finger board of the banjo – an instrument of Afro-American origin –

was not difficult for a musician to make and this allowed many fiddlers to adapt to the

banjo's rise in popularity.

These two instruments became particularly associated with the new American sound

which developed in the east coast and southern regions of the country – areas known

as Appalachia and the Ozarks – and which laid the foundations for Country and Western.」

【 フォークからカントリーへ

which developed in the east coast and southern regions of the country – areas known

as Appalachia and the Ozarks – and which laid the foundations for Country and Western.」

【 フォークからカントリーへ

アイルランド音楽は、アメリカ合衆国における音楽の発展に大きな影響を与えました。

アイルランド系やその他の移民たちが持ち込んだ音楽の技術は、既存の音楽スタイルと融合し

アメリカン・フォーク・ミュージックを生み出しました。

アイルランド系やその他の移民たちが持ち込んだ音楽の技術は、既存の音楽スタイルと融合し

アメリカン・フォーク・ミュージックを生み出しました。

特に、リールやホーンパイプといったダンスチューンのレパートリーを持つフィドル奏者は、

最も強い印象を残したようです。

最も強い印象を残したようです。

ユニークな音色を持つイーリアン・パイプも一部で演奏されましたが、そのあまりに

アイルランド的な響きがかえってアメリカの主流にはなりにくかったようです。

アイルランド的な響きがかえってアメリカの主流にはなりにくかったようです。

一方、フィドルからバンジョーへの移行は比較的容易でした。バンジョーはアフリカ系アメリカ人

起源の楽器であり、その人気の高まりとともに、多くのフィドル奏者が演奏に取り入れるように

なりました。

起源の楽器であり、その人気の高まりとともに、多くのフィドル奏者が演奏に取り入れるように

なりました。

このフィドルとバンジョーという2つの楽器は、アメリカの東海岸や南部、特にアパラチア山脈や

オザーク地方で発展した新しいアメリカ音楽と密接に結びつき、のちのカントリー&ウェスタン

音楽の土台を築くこととなりました。】

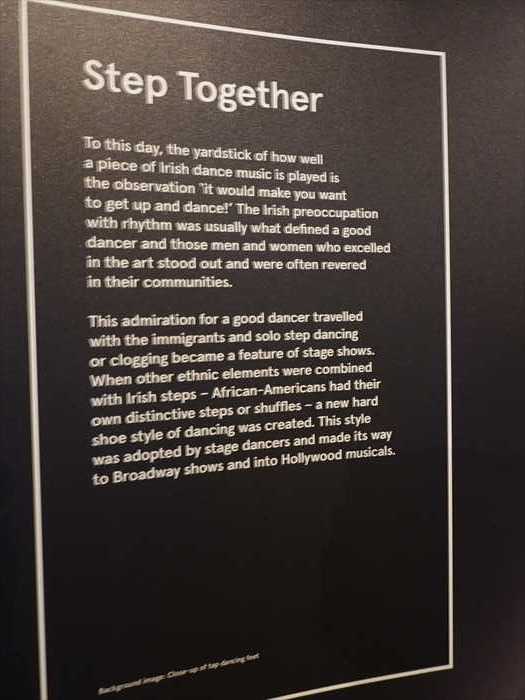

「 Step Together(共にステップを) 」の解説パネルです。 アイルランド系移民のダンス文化が、

アメリカでどのように変化・融合していったか を紹介していた。

「 Step Together

オザーク地方で発展した新しいアメリカ音楽と密接に結びつき、のちのカントリー&ウェスタン

音楽の土台を築くこととなりました。】

「 Step Together(共にステップを) 」の解説パネルです。 アイルランド系移民のダンス文化が、

アメリカでどのように変化・融合していったか を紹介していた。

「 Step Together

To this day, the yardstick of how well a piece of Irish dance music is played is the

observation "it would make you want to get up and dance!" The Irish preoccupation with

rhythm was usually what defined a good dancer and those men and women who excelled

in the art stood out and were often revered in their communities.

observation "it would make you want to get up and dance!" The Irish preoccupation with

rhythm was usually what defined a good dancer and those men and women who excelled

in the art stood out and were often revered in their communities.

This admiration for a good dancer travelled with the immigrants and solo step dancing or clogging became a feature of stage shows. When other ethnic elements were combined

with Irish steps – African-Americans had their own distinctive steps or shuffles –

a new hard shoe style of dancing was created. This style was adopted by stage dancers

and made its way to Broadway shows and into Hollywood musicals.」

【 共にステップを

with Irish steps – African-Americans had their own distinctive steps or shuffles –

a new hard shoe style of dancing was created. This style was adopted by stage dancers

and made its way to Broadway shows and into Hollywood musicals.」

【 共にステップを

今日に至るまで、アイルランドのダンス音楽がうまく演奏されているかどうかの基準は「思わず

踊り出したくなるかどうか」という点にあります。アイルランド人はリズムに強いこだわりを

持っており、それが優れたダンサーを定義する要素でした。そして、その芸に秀でた男女は

地域社会の中で際立った存在となり、しばしば敬意をもって称えられました。

踊り出したくなるかどうか」という点にあります。アイルランド人はリズムに強いこだわりを

持っており、それが優れたダンサーを定義する要素でした。そして、その芸に秀でた男女は

地域社会の中で際立った存在となり、しばしば敬意をもって称えられました。

この「優れたダンサーへの憧れ」は移民と共に旅をし、ソロのステップダンスやクロッグダンス

(木靴ダンス)は舞台ショーの見どころの一つとなっていきました。

(木靴ダンス)は舞台ショーの見どころの一つとなっていきました。

他の民族の要素がアイルランドのステップと組み合わさると──たとえばアフリカ系アメリカ人の

独自のステップやシャッフルなど──新たな「ハードシュー・スタイルのダンス」が生まれました。

独自のステップやシャッフルなど──新たな「ハードシュー・スタイルのダンス」が生まれました。

このスタイルは舞台のダンサーたちに取り入れられ、ブロードウェイのショーやハリウッドの

ミュージカルにまで発展していったのです。】

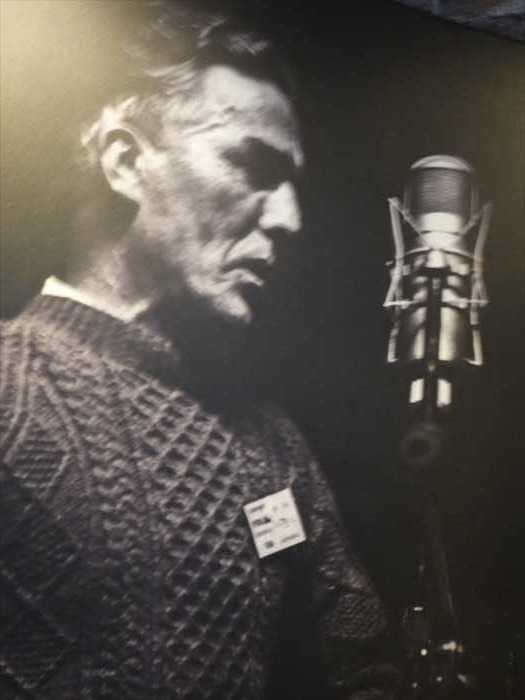

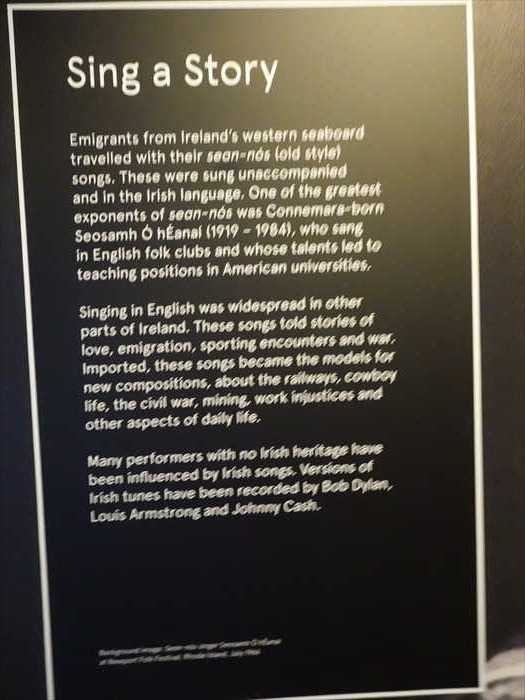

「 Sing a Story

ミュージカルにまで発展していったのです。】

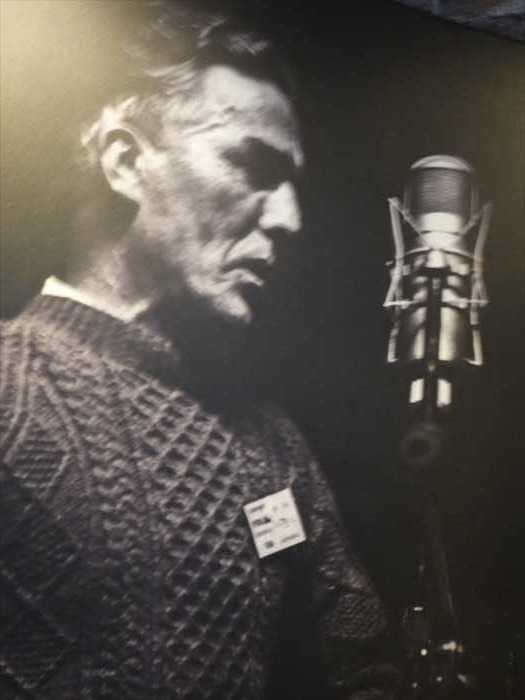

Seosamh Ó hÉanaí(ショーサム・オ・ヘナイ / Joe Heaney)

。

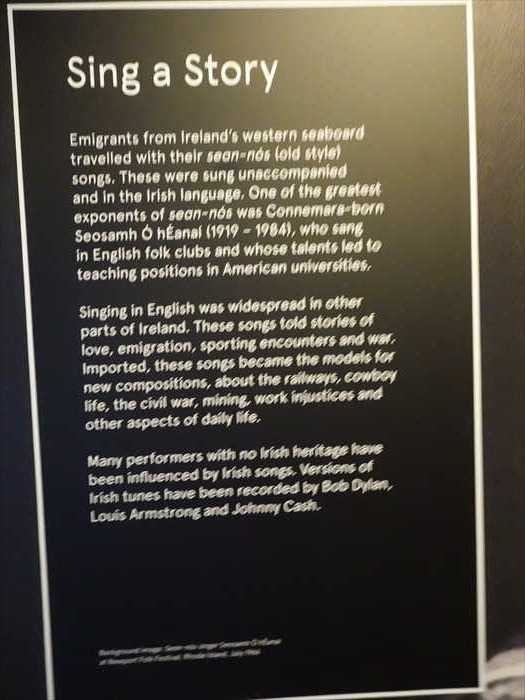

「 Sing a Story

Emigrants from Ireland's western seaboard travelled with their sean-nós (old style) songs.

These were sung unaccompanied and in the Irish language. One of the greatest

exponents of sean-nós was Connemara-born Seosamh Ó hÉanaí (1919–1984),

who sang in English folk clubs and whose talents led to teaching positions in American universities.

These were sung unaccompanied and in the Irish language. One of the greatest

exponents of sean-nós was Connemara-born Seosamh Ó hÉanaí (1919–1984),

who sang in English folk clubs and whose talents led to teaching positions in American universities.

Singing in English was widespread in other parts of Ireland. These songs told stories

of love, emigration, sporting encounters and war. Imported, these songs became

the models for new compositions, about the railways, cowboy life, the civil war, mining,

work injustices and other aspects of daily life.

of love, emigration, sporting encounters and war. Imported, these songs became

the models for new compositions, about the railways, cowboy life, the civil war, mining,

work injustices and other aspects of daily life.

Many performers with no Irish heritage have been influenced by Irish songs. Versions

of Irish tunes have been recorded by Bob Dylan, Louis Armstrong and Johnny Cash.」

【 物語を歌う

of Irish tunes have been recorded by Bob Dylan, Louis Armstrong and Johnny Cash.」

【 物語を歌う

アイルランド西海岸出身の移民たちは、sean-nós(シャン・ノース、古い様式)の歌を携えて

旅立ちました。これらの歌は無伴奏で、アイルランド語で歌われました。sean-nós の偉大な

担い手の一人が、コネマラ出身の ショーサム・オ・ヘナイ(Seosamh Ó hÉanaí、1919–1984)

です。彼はイングランドのフォーククラブで歌い、その才能からアメリカの大学で教鞭を

とるまでになりました。

旅立ちました。これらの歌は無伴奏で、アイルランド語で歌われました。sean-nós の偉大な

担い手の一人が、コネマラ出身の ショーサム・オ・ヘナイ(Seosamh Ó hÉanaí、1919–1984)

です。彼はイングランドのフォーククラブで歌い、その才能からアメリカの大学で教鞭を

とるまでになりました。

アイルランドの他地域では、英語で歌われる歌が広まりました。これらは、恋愛、移住、

スポーツの出来事、戦争といった物語を語るものでした。移民とともにアメリカに持ち込まれた

これらの歌は、鉄道、西部開拓、南北戦争、鉱山労働、労働の不正義など、日常生活に関する

新たな作曲の手本となりました。

スポーツの出来事、戦争といった物語を語るものでした。移民とともにアメリカに持ち込まれた

これらの歌は、鉄道、西部開拓、南北戦争、鉱山労働、労働の不正義など、日常生活に関する

新たな作曲の手本となりました。

アイルランドにルーツを持たない多くのアーティストたちも、アイルランドの歌から影響を

受けています。 アイルランドの旋律を元にした楽曲は、ボブ・ディラン、

ルイ・アームストロング、ジョニー・キャッシュといったアーティストたちにも

録音されています。】

「 アイルランド移民と舞台芸術 」に関係する内容が紹介

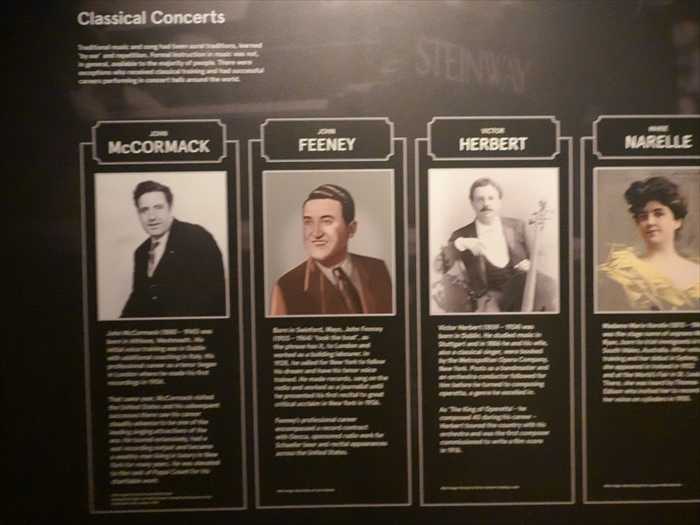

アイルランド系の著名なクラシック音楽家たち を紹介する展示「Classical Concerts」の一部。

左から

1.John McCORMACK

アメリカ音楽界におけるアイルランド系音楽や歌の影響を示す

「 Tin Pan Alley(ティン・パン・アレー) 」に関するもの。

「 Tin Pan Alley

受けています。 アイルランドの旋律を元にした楽曲は、ボブ・ディラン、

ルイ・アームストロング、ジョニー・キャッシュといったアーティストたちにも

録音されています。】

「 アイルランド移民と舞台芸術 」に関係する内容が紹介

赤いカーテンに囲まれた「小劇場」風のディスプレイでは、モニターに白いドレスを着た

人物が登場する映像が流れていた。

人物が登場する映像が流れていた。

有名なアイルランド系の舞台女優、またはオペラ歌手のパフォーマンスを紹介する映像か?

ミュージカルやバラエティ・ショーにおけるアイルランド系移民の貢献を示している

のであろう。

のであろう。

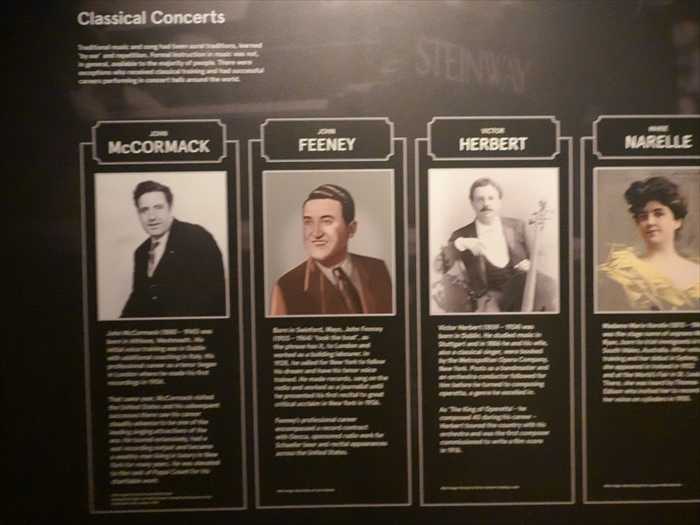

アイルランド系の著名なクラシック音楽家たち を紹介する展示「Classical Concerts」の一部。

左から

1.John McCORMACK

1884年アイルランドのアスローン生まれの世界的なテノール歌手。

2.John FEENEY

1896年、メイヨー州スウィンフォード生まれのバリトン歌手。

3.Victor HERBERT

2.John FEENEY

1896年、メイヨー州スウィンフォード生まれのバリトン歌手。

3.Victor HERBERT

1859年ドイツ生まれ(アイルランド系)。作曲家、チェリスト、指揮者。

4.Marie NARELLE

4.Marie NARELLE

1870年、オーストラリア生まれの歌手。本名は Catherine Mary Ryan。

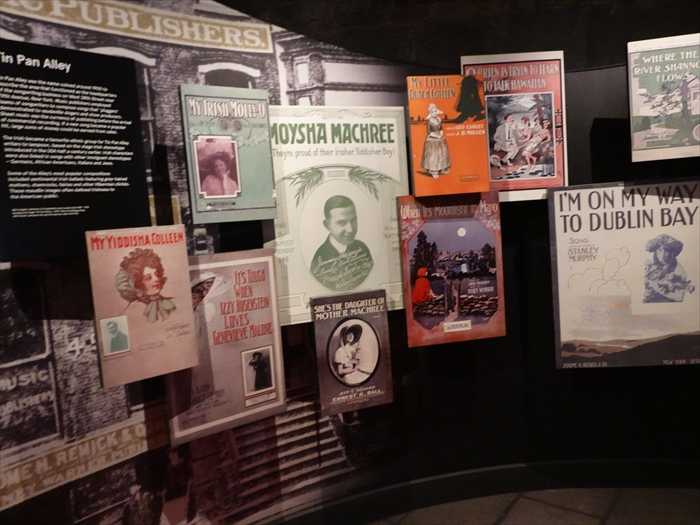

アメリカ音楽界におけるアイルランド系音楽や歌の影響を示す

「 Tin Pan Alley(ティン・パン・アレー) 」に関するもの。

「 Tin Pan Alley

The place where popular music was made.

In the early 20th century, a number of music publishers and songwriters set up business

in a part of New York City that became known as Tin Pan Alley. It was here that the

sheet music industry flourished and where the business of creating and marketing

popular songs took off.

in a part of New York City that became known as Tin Pan Alley. It was here that the

sheet music industry flourished and where the business of creating and marketing

popular songs took off.

Irish American composers and lyricists were among the most successful.

They included men like Chauncey Olcott, Ernest R. Ball, and George M. Cohan.

They included men like Chauncey Olcott, Ernest R. Ball, and George M. Cohan.

The songs they created often sentimentalized Irish identity, telling tales of emigration,

motherly love, and longing for the old country. The popularity of these songs helped

to shape perceptions of Irishness in America and beyond.」

【 ティン・パン・アレー

motherly love, and longing for the old country. The popularity of these songs helped

to shape perceptions of Irishness in America and beyond.」

【 ティン・パン・アレー

ポピュラー音楽が生まれた場所

20世紀初頭、ニューヨーク市の一角に数多くの音楽出版社や作詞・作曲家が拠点を構え、

この地域は「ティン・パン・アレー」として知られるようになりました。ここでは楽譜産業が

繁栄し、ポピュラー音楽の創作と販売が本格的に始まりました。

この地域は「ティン・パン・アレー」として知られるようになりました。ここでは楽譜産業が

繁栄し、ポピュラー音楽の創作と販売が本格的に始まりました。

アイルランド系アメリカ人の作曲家や作詞家たちは、その中でも特に成功を収めました。

彼らの中には、チャンシー・オルコット、アーネスト・R・ボール、ジョージ・M・コーハンと

いった人物が含まれます。

彼らの中には、チャンシー・オルコット、アーネスト・R・ボール、ジョージ・M・コーハンと

いった人物が含まれます。

彼らが生み出した楽曲はしばしばアイルランド人としてのアイデンティティを感傷的に描き、

移民の物語や母の愛、故郷への郷愁などをテーマにしていました。こうした楽曲の人気は、

アメリカ国内はもちろんのこと、国境を越えて「アイルランドらしさ」への認識を形成する

一助となりました。】

「 Classical Concerts

移民の物語や母の愛、故郷への郷愁などをテーマにしていました。こうした楽曲の人気は、

アメリカ国内はもちろんのこと、国境を越えて「アイルランドらしさ」への認識を形成する

一助となりました。】

「 Classical Concerts

Traditional music and song had been aural traditions, learned ‘by ear’ and repetition.

Formal instruction in music was not, in general, available to the majority of people.

There were exceptions who received classical training and had successful careers

performing in concert halls around the world.」

【 クラシック・コンサート

performing in concert halls around the world.」

【 クラシック・コンサート

伝統音楽や歌は、聴覚によって伝承され、「耳で聞いて」学び、繰り返しによって身に

つけられてきました。

つけられてきました。

音楽の正式な教育は、一般的に多くの人々には提供されていませんでした。

しかし、例外としてクラシック音楽の訓練を受け、世界各地のコンサートホールで成功した

キャリアを築いた人々もいました。

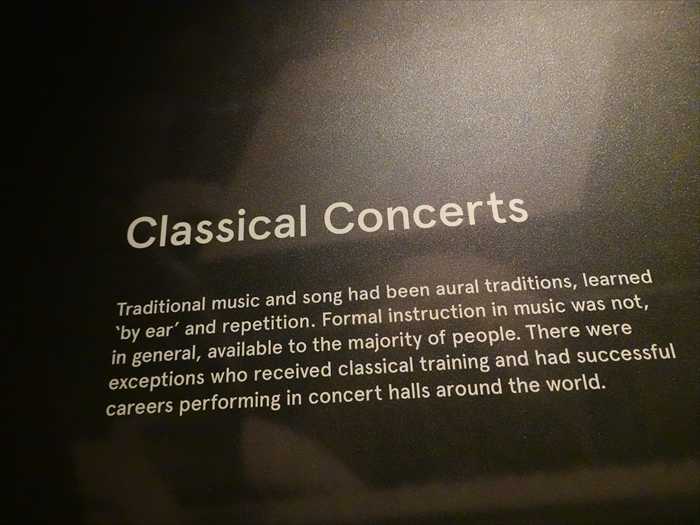

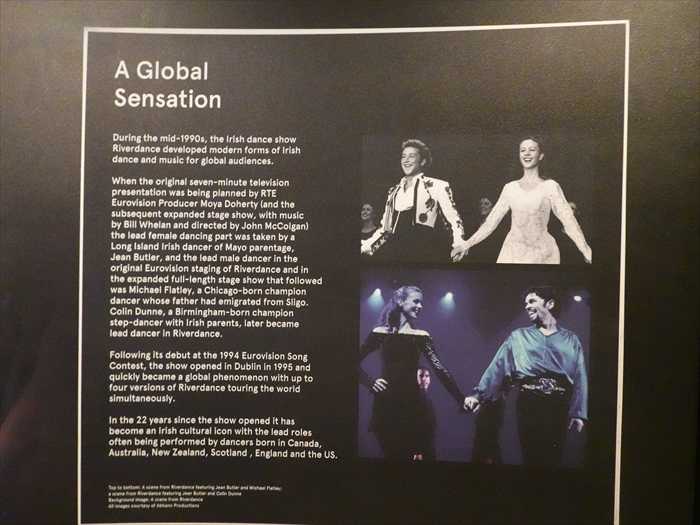

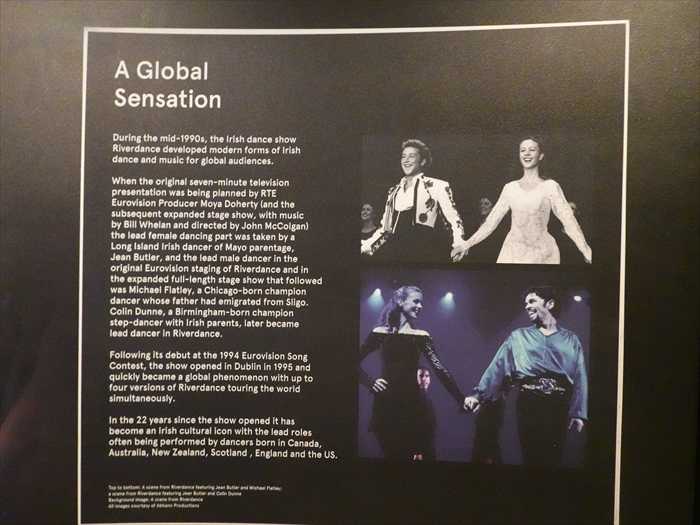

「 A Global Sensation

キャリアを築いた人々もいました。

「 A Global Sensation

During the mid-1990s, the Irish dance show Riverdance developed modern forms of

Irish dance and music for global audiences.

Irish dance and music for global audiences.

When the original seven-minute television presentation was being planned by RTE

Eurovision Producer Moya Doherty (and the subsequent expanded stage show, with

music by Bill Whelan and directed by John McColgan)

music by Bill Whelan and directed by John McColgan)

the lead female dancing part was taken by a Long Island Irish dancer of Mayo parentage,

Jean Butler, and the lead male dancer in the original Eurovision staging of Riverdance and

in the expanded full-length stage show that followed was Michael Flatley, a Chicago-born champion dancer whose father had emigrated from Sligo.Colin Dunne, a Birmingham-born championstep-dancer with Irish parents, later became lead dancer in Riverdance.

in the expanded full-length stage show that followed was Michael Flatley, a Chicago-born champion dancer whose father had emigrated from Sligo.Colin Dunne, a Birmingham-born championstep-dancer with Irish parents, later became lead dancer in Riverdance.

Following its debut at the 1994 Eurovision Song Contest, the show opened in Dublin

in 1995 and quickly became a global phenomenon with up to four versions of

Riverdance touring the world simultaneously.

in 1995 and quickly became a global phenomenon with up to four versions of

Riverdance touring the world simultaneously.

In the 22 years since the show opened it has become an Irish cultural icon with the lead

roles often being performed by dancers born in Canada,

roles often being performed by dancers born in Canada,

Australia, New Zealand, Scotland, England and the US.」

【 世界的センセーション

【 世界的センセーション

1990年代半ば、アイルランドのダンスショー《リバーダンス》は、アイリッシュ・ダンスと

音楽の現代的な形を発展させ、世界中の観客に届けられるようになりました。

音楽の現代的な形を発展させ、世界中の観客に届けられるようになりました。

最初の7分間のテレビ放送が、RTÉ(アイルランド放送協会)のユーロビジョン・プロデューサー、

モヤ・ドハティによって企画されていた際(その後、音楽はビル・ウィーラン、演出は

ジョン・マッコルガンによって拡張されたステージショーが制作された)、女性の主役

ダンサーにはメイヨー県出身の両親をもつロングアイランド在住のアイルランド系ダンサー、

ジーン・バトラーが選ばれました。

モヤ・ドハティによって企画されていた際(その後、音楽はビル・ウィーラン、演出は

ジョン・マッコルガンによって拡張されたステージショーが制作された)、女性の主役

ダンサーにはメイヨー県出身の両親をもつロングアイランド在住のアイルランド系ダンサー、

ジーン・バトラーが選ばれました。

そして、オリジナルのユーロビジョン版《リバーダンス》、およびその後に制作された

全長ステージショーで男性の主役を務めたのは、父親がスライゴーから移住してきたシカゴ出身の

チャンピオン・ダンサー、マイケル・フラットリーでした。

全長ステージショーで男性の主役を務めたのは、父親がスライゴーから移住してきたシカゴ出身の

チャンピオン・ダンサー、マイケル・フラットリーでした。

後に、アイルランド人の両親をもつバーミンガム出身のチャンピオン・ステップダンサー、

コリン・ダンが《リバーダンス》の主役を引き継ぎました。

コリン・ダンが《リバーダンス》の主役を引き継ぎました。

1994年のユーロビジョン・ソング・コンテストでの初披露の後、1995年にダブリンで正式に

公演が始まりました。そして、このショーは瞬く間に世界的な現象となり、最大4つの

《リバーダンス》のカンパニーが同時に世界各地を巡回する規模となりました。

公演が始まりました。そして、このショーは瞬く間に世界的な現象となり、最大4つの

《リバーダンス》のカンパニーが同時に世界各地を巡回する規模となりました。

初演から22年の間に、このショーはアイルランド文化の象徴的存在となり、主役の多くはカナダ、

オーストラリア、ニュージーランド、スコットランド、イングランド、アメリカ合衆国などで

生まれたダンサーたちによって演じられています。】

「 Hollywood to Broadway 」。

ピンボケにて解読不能。

オーストラリア、ニュージーランド、スコットランド、イングランド、アメリカ合衆国などで

生まれたダンサーたちによって演じられています。】

「 Hollywood to Broadway 」。

ピンボケにて解読不能。

・・・もどる・・・

・・・つづく・・・

・・・つづく・・・

お気に入りの記事を「いいね!」で応援しよう

【毎日開催】

15記事にいいね!で1ポイント

10秒滞在

いいね!

--

/

--

© Rakuten Group, Inc.