PR

X

Keyword Search

▼キーワード検索

Comments

私はイスラム教徒です@ Re:アイルランド・ロンドンへの旅(その131): ロンドン散策記・アルバート記念碑(Albert Memorial)-2(11/06)

神神は言った: コーランで 『 (21) 人々…

私はイスラム教徒です@ Re:アイルランド・ロンドンへの旅(その122): ロンドン散策記・Victoria and Albert Museum・ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館-5(10/28)

神神は言った: コーランで 『 (21) 人…

続日本100名城東北の…

New!

オジン0523さん

【甥のステント挿入… New!

Gママさん

New!

Gママさん

2025年版・岡山大学… New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

ムベの実を開くコツ… noahnoahnoahさん

noahnoahnoahさん

エコハウスにようこそ ecologicianさん

【甥のステント挿入…

New!

Gママさん

New!

Gママさん2025年版・岡山大学…

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

New!

隠居人はせじぃさんムベの実を開くコツ…

noahnoahnoahさん

noahnoahnoahさんエコハウスにようこそ ecologicianさん

Calendar

カテゴリ: 海外旅行

【 海外旅行 ブログリスト

】👈️リンク

V&A(ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館/ロンドン) 日本展示室に掛けられている 浮世絵(木版画) 。

額装されているのは主に 歌舞伎や武者絵を題材にした錦絵で、江戸末期〜明治期の作品 。

「 Legendary Women in Japanese Prints

ways in which women came to be depicted: dangerous, talented and powerful.」

浮世絵に描かれた伝説的な女性たち

これらの版画は、日本の版画師たちの創造力を示すだけでなく、女性がいかに危険で、

才能に満ち、力強い存在として描かれてきたかを物語っている。】

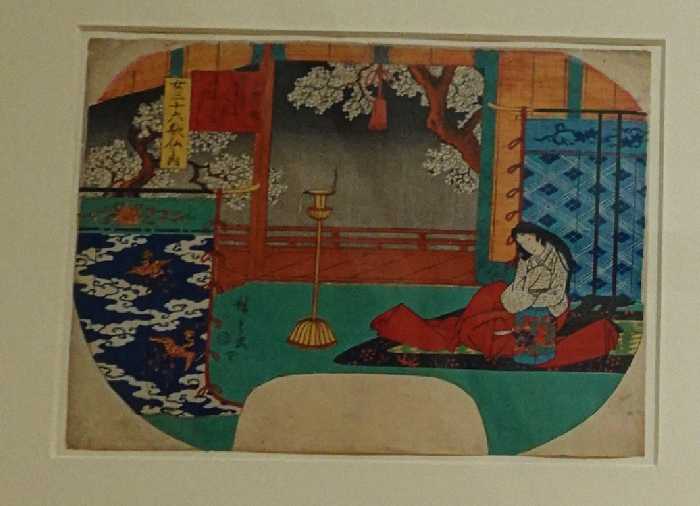

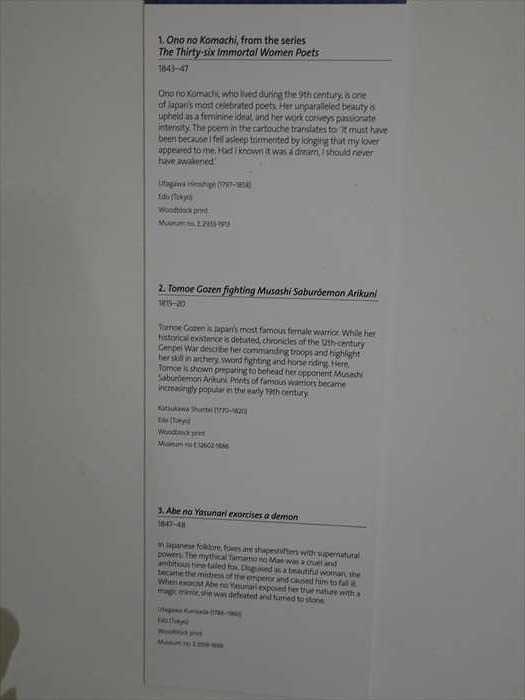

左上: 1.小野小町 《女三十六歌仙》シリーズより 団扇絵

右上: 2.巴御前、武蔵三郎衛門有国と戦う図

下 : 3.安倍泰成、妖狐を退治する図

1.小野小町 《女三十六歌仙》シリーズより 団扇絵

2.巴御前、武蔵三郎衛門有国と戦う図 をネットから。

3.安倍泰成、妖狐を退治する図 をネットから。

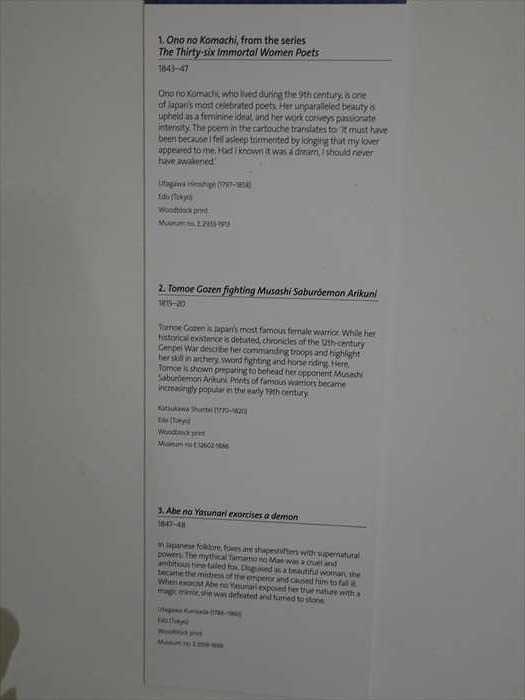

「 1. Ono no Komachi, from the series The Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets

1.小野小町

「 2. Tomoe Gozen fighting Musashi Saburōemon Arikuni

【 2.巴御前、武蔵三郎衛門有国と戦う図

3. Abe no Yasunari exorcises a demon

【 3.安倍泰成、妖狐を退治する図

左:4.神功皇后と武内宿禰(たけうちのすくね)

中央左:5.二代目 岩井粂三郎の揚巻役

中央右:6.木曽のお六の櫛

右下:7.厳島における弁才天の顕現が平清盛を圧倒する図

「 4. Empress Jingû and Minister Takeuchi,

【 神功皇后と武内宿禰(たけうちのすくね)

「 5. The Actor Iwai Kumesaburō II as Agemaki

【 5.二代目 岩井粂三郎の揚巻役

「 6.Kiso no Oroku Combs, from the series A Compendium of Famous Artisans

【 6.木曽のお六の櫛

「 7. The manifestation of Benzaiten overwhelming Taira no Kiyomori at Miyajima

【 7.厳島における弁才天の顕現が平清盛を圧倒する図

7.厳島における弁才天の顕現が平清盛を圧倒する図

V&A日本展示室(Room 45, Toshiba Gallery of Japanese Art) の一角、浮世絵コーナー

とは別のガラスケースを振り返って。

「日本の陶磁器・漆工芸の国際交流」 をテーマにした展示で、江戸期の肥前磁器

(伊万里焼・柿右衛門様式など)を中心に、西洋輸出向けの豪華な大皿・壺を紹介。

ウォーターフォール・オン・カラーズ(水の色彩滝) 千住博 。

「 Waterfall on Colors

【 ウォーターフォール・オン・カラーズ(水の色彩滝)

再び 「根付(netsuke)、印籠(inrō)、小型漆器」などの展示コーナー を。

根付 (netsuke) コレクション に近づいて。

「 Netsuke

【 根付(ねつけ)

ここに展示されている根付の大半は、1700年から1870年の間に制作されたものである。】

なんとか解読できました。

根付と一緒に展示される 印籠(inrō)とその付属品(緒締め・根付) 👈️リンク のコーナー。

「 Smoking

Tobacco was introduced to Japan by the Portuguese in the late 16th century.

Despite attempts to ban it, smoking became popular among both men and women.

Men carried personal smoking sets consisting of a tobacco container, a pipe and

a pipe-holder. These were hung from the waist and held in place by toggles called

netsuke. Both men and women used communal smoking cabinets, which were usually

made from decorated lacquer. These incorporated small braziersfor burning charcoal

with which to light the pipe.」

【 喫煙

そこには小型の火鉢が組み込まれており、炭を焚いて煙管に火を点けることができた。】

根付(netsuke)展示ケース の全景。

「 Netsuke

【 根付(ねつけ)

ここに展示されている根付の大部分は 1700年から1870年の間に制作されたものである。】

着物・衣装コーナー を再び。

「 Kimono for Men

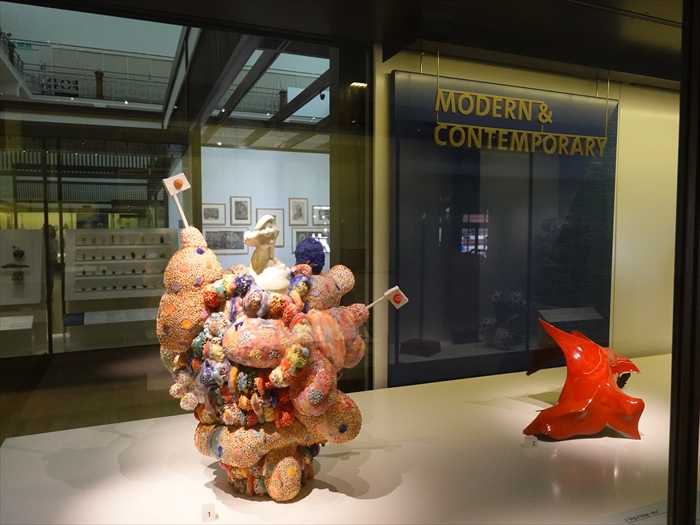

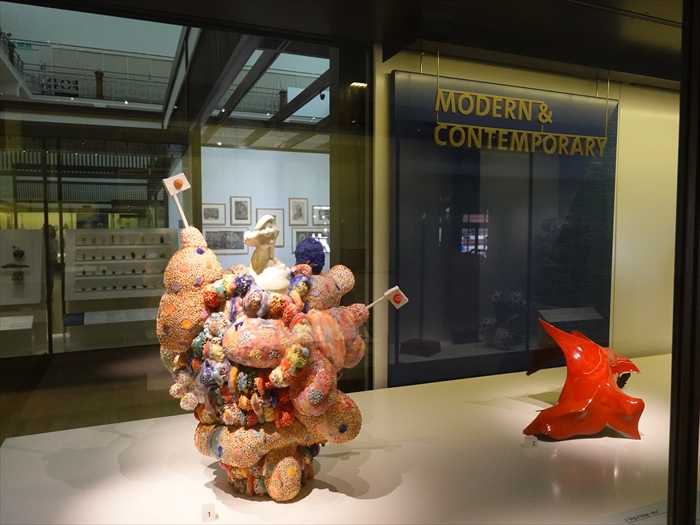

「 MODERN & CONTEMPORARY(現代日本美術) 」展示コーナー。

極彩色の現代陶芸作品 をアップで。 Heart on Wave 川合 一仁。

「 Studio Crafts

Today, many Japanese makers use traditional craft media to create unique works of art.

They are supported by an extensive system of art colleges and a well-developed art

market in Japan. Numerous craft associations also encourage their activities, as do

regular competitive exhibitions. All the objects have been made since 2010, many of

them very recently.」

【スタジオ・クラフト(現代工芸)

今日、多くの日本の作り手は、伝統的な工芸の素材や技法を用いて、独自の芸術作品を創り

出している。彼らの活動は、日本の充実した美術大学の制度や発達した美術市場によって

支えられている。また、数多くの工芸団体がその活動を奨励しており、定期的に行われる

公募展や競技的な展覧会も後押しとなっている。ここに展示されている作品はすべて

2010年以降に制作されたもので、多くはごく最近のものである。】

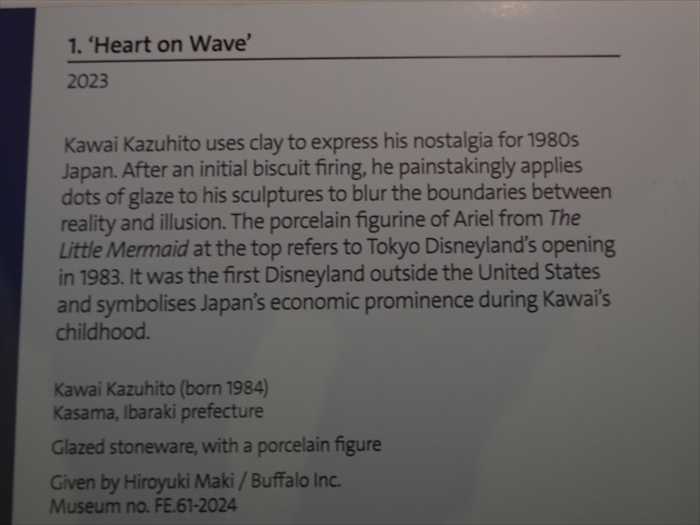

「 1. ‘Heart on Wave’

【1. Heart on Wave(波の上の心)

2023年

川合一仁(かわい かずひと)は、1980年代日本への郷愁を粘土で表現している。素焼きの後、

彼は現実と幻想の境界を曖昧にするために、丹念に釉薬の点を彫刻表面に施す。作品上部

にある『リトル・マーメイド』のアリエルの磁器人形は、1983年に開園した

東京ディズニーランドを示唆している。それは米国以外で初めてのディズニーランドであり、

川合の幼少期における日本の経済的繁栄を象徴している。

川合 一仁(1984年生)

茨城県笠間市

釉薬を施した炻器、

磁器製人形付き寄贈:牧浩之/Buffalo Inc.

所蔵番号:FE.61-2024】

こちらも「MODERN & CONTEMPORARY(現代・現代美術)」セクション。

木工によるデザイン作品(おそらく屏風風の木製パネルや円形構造物) コーナー。

中央に展示されているのは、木工によるデザイン作品(おそらく屏風風の木製パネルや

円形構造物)で、横には椅子や織物、籠などが並んでいた。

メモリー 熊井恭子 。

「 Studio Crafts

【 スタジオ工芸

「1. 'Memory'2017Kumai Kyoko is an internationally recognised fibre artist.

She created this work in remembrance of the Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami of

2011, which caused over 15,000 deaths. Kumai works mainly with stainless steel wire.

Here she has shapedthe wire into a bundle of organic forms. These represent people’s

feelings about the unforgettable disaster that has had a lasting impact in Japan.

Kumai Kyoko (born 1943)

Tokyo

Stainless steel wire

Given anonymously

Museum no. FE.57-2023」

【1. メモリー2017年熊井恭子は国際的に認められたファイバー・アーティストです。

彼女は2011年の東北大震災と津波(死者15,000人以上)を追悼して、この作品を

制作しました。熊井は主にステンレススチールワイヤーを用いて制作を行います。

ここではワイヤーを有機的な形態の束に組み上げ、それを通じて日本に長く影響を残した

忘れがたい災害に対する人々の感情を表現しています。

熊井恭子(1943年生まれ)

東京

素材:ステンレススチールワイヤー

寄贈:匿名寄贈

館蔵番号:FE.57-2023】

「民芸・復興(Discovery and Revival)」セクションの一部で、柳宗悦の民芸運動の文脈で

紹介されている作品群。

藍染の幕(のれん/幔幕の類) で、流水に菊の花、さらに上部に家紋が配された文様 。

「 Discovery and Revival

An interest in folk crafts arose in Japan in the early 20th century as a reaction to rapid industrialisation and urbanisation. Still active today, the Japanese Folk Craftmovement

was established in 1926 by the critic and theorist Yanagi Soetsu. He and his followers

collected historical folk crafts and founded museums in whichto show them.

They also encouraged the preservation of traditional craft techniquesand the making of contemporary work in the style and spirit of historical models.」

【 発見と復興

20世紀初頭、日本では急速な工業化と都市化への反動として、民芸(フォーククラフト)への

関心が高まりました。現在も活動が続いている日本民芸運動は、1926年に批評家で理論家の

柳宗悦によって設立されました。柳とその仲間たちは歴史的な民芸品を収集し、それらを

展示するための博物館を設立しました。また、伝統的な工芸技術の保存と、歴史的な様式と

精神に基づいた現代作品の制作を奨励しました。】

「 5. Bedding cover

【 5. 布団カバー

伊万里焼・柿右衛門様式を中心とした日本磁器(17~18世紀) 。

特に ヨーロッパに輸出された伊万里焼や柿右衛門様式のコレクションが多く展示 されている と。

「 Porcelain for Europe

Porcelain was first made in Japan in the early 17th century at kilns in and around

the town of Arita. The earliest pieces were designed for the domestic market.

In 1644,following the fall of the Ming dynasty, Chinese porcelain became temporarily

unavailable and the Dutch turned to Japan as an alternative source for this

highlysought-after commodity. Japan increased its output of porcelain, with much of

it being aimed at the export market and often made in shapes copying

Europeanceramics.」

【 ヨーロッパ向けの磁器 日本で磁器が初めて作られたのは17世紀初頭、有田の町およびその

周辺の窯においてでした。最初の作品は国内市場向けにデザインされていました。

1644年、明王朝の滅亡に伴い、中国磁器が一時的に入手できなくなると、オランダ人はこの

需要の高い商品を得るために日本を代替供給地としました。日本は磁器の生産量を増加させ、

その多くを輸出市場に向け、しばしばヨーロッパの陶磁器の形を模した作品を作りました。】

「 Europe in Japan The first Europeans to reach Japan were the Portuguese. Arriving in

the early 1540s, they brought with them guns and Christianity. The latter ultimately

proved unwelcome. Christianity was banned and the Portuguese were expelled.

From 1639 the Dutch were the only Europeans permitted to trade with Japan.

They were kept under close scrutinyon Dejima, an artificial island in Nagasaki Bay.

Despite the restrictions placed on the Dutch, the goods and scientific knowledge

they brought with them werethe subject of both scholarly enquiry and popular interest.」

【 日本におけるヨーロッパ 日本に最初に到達したヨーロッパ人はポルトガル人でした。

1540年代初頭に到来し、鉄砲とキリスト教をもたらしました。しかし後者(キリスト教)は

最終的に歓迎されず、禁教とともにポルトガル人は追放されました。1639年以降、日本と交易を

許された唯一のヨーロッパ人はオランダ人だけとなりました。彼らは長崎湾の人工島・出島に

厳重な監視のもとで滞在しました。制限が課されていたにもかかわらず、オランダ人が

もたらした商品や科学的知識は、学問的探求や一般の関心の対象となりました。】

これは「南蛮漆器(Nanban lacquerware)」の 代表的な輸出用大型箱(coffer / chest) 。「 Kamaboko(蒲鉾型) 」のドーム状蓋をもつ大型キャビネット。

「 Lacquer for Europe

When the Europeans came to Japan in the mid-1500s, they were immediately

by the lustre and decorative brilliance of objects made from lacquer (urushi).

The Japanese soon began to produce lacquer items for export copying European

shapes. Early pieces were decorated in mother-of-pearl using techniques similar

to those found in China, Korea and India. Export lacquer from the 1600s onwards

was decorated primarily in gold on black, and featured elaborate pictorial schemes.」

【 ヨーロッパ向けの漆器

1500年代半ばにヨーロッパ人が日本に来航したとき、彼らはすぐに漆(うるし)で作られた

器物の光沢と装飾的な華やかさに魅了されました。やがて日本人はヨーロッパの器物の形を

写した輸出用漆器を生産するようになります。初期の作品は螺鈿(らでん)で装飾され、

中国・朝鮮・インドで見られる技法と類似していました。1600年代以降の輸出漆器は、

黒地に金を主体とした装飾が施され、精緻な絵画的意匠が特徴となりました。】

「 1. The Mazarin Chest

【 1. マザラン・チェスト(Mazarin Chest)

・・・ もどる ・・・

・・・ つづく ・・・

V&A(ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館/ロンドン) 日本展示室に掛けられている 浮世絵(木版画) 。

額装されているのは主に 歌舞伎や武者絵を題材にした錦絵で、江戸末期〜明治期の作品 。

「 Legendary Women in Japanese Prints

Woodblock prints were an affordable art that could be enjoyed by people of all ages,

genders and social classes. In the 19th century printed images of illustrious and

notorious women found new popularity in Japan. Going beyond conventional images

of female beauty, government directives to improve social morality encouraged the

portrayal of women of exemplary strength and skill, while literature and drama

delighted in villains who were ready to bewitch and betray.

These prints show not only the creativity of Japan’s printmakers, but also the manygenders and social classes. In the 19th century printed images of illustrious and

notorious women found new popularity in Japan. Going beyond conventional images

of female beauty, government directives to improve social morality encouraged the

portrayal of women of exemplary strength and skill, while literature and drama

delighted in villains who were ready to bewitch and betray.

ways in which women came to be depicted: dangerous, talented and powerful.」

浮世絵に描かれた伝説的な女性たち

木版画は、あらゆる年齢・性別・社会階層の人々が楽しめる手頃な芸術であった。

19世紀になると、日本では高名な女性や悪名高い女性の姿を描いた版画が新たな

人気を博した。従来の美人画の枠を超え、社会道徳を向上させるための幕府の指導は、

優れた力と技を備えた女性像の描写を奨励した。一方で文学や演劇は、人を惑わし裏切る

妖しい悪女像を喜んで描いた。

19世紀になると、日本では高名な女性や悪名高い女性の姿を描いた版画が新たな

人気を博した。従来の美人画の枠を超え、社会道徳を向上させるための幕府の指導は、

優れた力と技を備えた女性像の描写を奨励した。一方で文学や演劇は、人を惑わし裏切る

妖しい悪女像を喜んで描いた。

これらの版画は、日本の版画師たちの創造力を示すだけでなく、女性がいかに危険で、

才能に満ち、力強い存在として描かれてきたかを物語っている。】

左上: 1.小野小町 《女三十六歌仙》シリーズより 団扇絵

右上: 2.巴御前、武蔵三郎衛門有国と戦う図

下 : 3.安倍泰成、妖狐を退治する図

1.小野小町 《女三十六歌仙》シリーズより 団扇絵

2.巴御前、武蔵三郎衛門有国と戦う図 をネットから。

3.安倍泰成、妖狐を退治する図 をネットから。

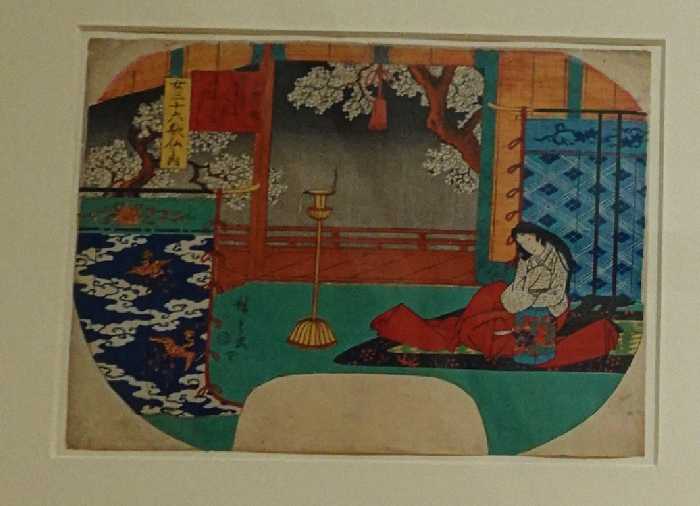

「 1. Ono no Komachi, from the series The Thirty-six Immortal Women Poets

1843–47

Ono no Komachi, who lived during the 9th century, is one of Japan’s most celebrated

poets. Her unparalleled beauty is upheld as a feminine ideal, and her work conveys

passionate intensity. The poem in the cartouche translates to:

poets. Her unparalleled beauty is upheld as a feminine ideal, and her work conveys

passionate intensity. The poem in the cartouche translates to:

‘It must have been because I fell asleep tormented by longing that my lover

appeared to me. Had I known it was a dream, I should never have awakened.’

appeared to me. Had I known it was a dream, I should never have awakened.’

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

Edo (Tokyo)

Woodblock print

Museum no. E.2933-1913」 1.小野小町

《女三十六歌仙》シリーズより

1843–47年

9世紀に生きた小野小町は、日本で最も著名な歌人の一人である。比類なき美しさは女性の

理想像として称えられ、その和歌は情熱的な切実さを伝えている。画中の詞書に記された

歌の現代語訳は次の通り:

理想像として称えられ、その和歌は情熱的な切実さを伝えている。画中の詞書に記された

歌の現代語訳は次の通り:

『 思ひつつ寝ればや人の見えつらむ 夢と知りせば覚めざらましを

』

「恋い焦がれて眠りに落ちたために、夢にあなたが現れたのだろう。夢と知っていたなら、

決して目覚めたりはしなかったのに。」

決して目覚めたりはしなかったのに。」

作者:歌川広重(1797–1858)

制作地:江戸(東京)

技法:木版画

所蔵番号:E.2933-1913】「 2. Tomoe Gozen fighting Musashi Saburōemon Arikuni

1815–20

Tomoe Gozen is Japan’s most famous female warrior. While her historical existence is

debated, chronicles of the 12th-century Genpei War describe her commanding troops

and highlight her skill in archery, sword fighting and horse riding. Here, Tomoe is shown preparing to behead her opponent Musashi Saburōemon Arikuni. Prints of famous

warriors became increasingly popular in the early 19th century.

debated, chronicles of the 12th-century Genpei War describe her commanding troops

and highlight her skill in archery, sword fighting and horse riding. Here, Tomoe is shown preparing to behead her opponent Musashi Saburōemon Arikuni. Prints of famous

warriors became increasingly popular in the early 19th century.

Katsukawa Shuntei (1770–1820)

Edo (Tokyo)

Woodblock print

Museum no. E.12602-1886」【 2.巴御前、武蔵三郎衛門有国と戦う図

1815–20年

巴御前は、日本でもっとも有名な女武者である。史実性については議論があるが、12世紀の

源平合戦の記録には、彼女が軍勢を指揮し、弓術・剣術・馬術に優れていたことが描かれている。

本作では、巴御前が敵将武蔵三郎衛門有国を斬首しようとする場面が表されている。

19世紀初頭、有名武将を描いた浮世絵はますます人気を高めていった。

源平合戦の記録には、彼女が軍勢を指揮し、弓術・剣術・馬術に優れていたことが描かれている。

本作では、巴御前が敵将武蔵三郎衛門有国を斬首しようとする場面が表されている。

19世紀初頭、有名武将を描いた浮世絵はますます人気を高めていった。

作者:勝川春亭(1770–1820)

制作地:江戸(東京)

技法:木版画

所蔵番号:E.12602-1886】3. Abe no Yasunari exorcises a demon

1847–48

In Japanese folklore, foxes are shapeshifters with supernatural powers.

The mythical Tamamo no Mae was a cruel and ambitious nine-tailed fox. Disguised as a beautifulwoman, she became the mistress of the emperor and caused him to fall ill.

When exorcist Abe no Yasunari exposed her true nature with a magic mirror, she was

defeated and turned to stone.

The mythical Tamamo no Mae was a cruel and ambitious nine-tailed fox. Disguised as a beautifulwoman, she became the mistress of the emperor and caused him to fall ill.

When exorcist Abe no Yasunari exposed her true nature with a magic mirror, she was

defeated and turned to stone.

Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865)

Edo (Tokyo)

Woodblock print

Museum no. E.5558-1886」【 3.安倍泰成、妖狐を退治する図

1847–48年

日本の伝承において、狐は超自然的な力を持つ変化の存在とされてきた。伝説の玉藻前

(たまものまえ)は、残酷で野心的な九尾の狐であり、美しい女性に姿を変えて帝の寵姫となり、

病に陥らせた。陰陽師・安倍泰成は、魔法の鏡によってその正体を暴き、彼女は敗北して

石に変じたと伝えられる。

(たまものまえ)は、残酷で野心的な九尾の狐であり、美しい女性に姿を変えて帝の寵姫となり、

病に陥らせた。陰陽師・安倍泰成は、魔法の鏡によってその正体を暴き、彼女は敗北して

石に変じたと伝えられる。

作者:歌川国貞(1786–1865)

制作地:江戸(東京)

技法:木版画

所蔵番号:E.5558-1886】

左:4.神功皇后と武内宿禰(たけうちのすくね)

中央左:5.二代目 岩井粂三郎の揚巻役

中央右:6.木曽のお六の櫛

右下:7.厳島における弁才天の顕現が平清盛を圧倒する図

「 4. Empress Jingû and Minister Takeuchi,

from the series Banners as Interior Decoration

1844–62

Before the Imperial Household Law of 1889 prevented female succession, eight of

Japan’s historical rulers were women. Empress Jingû is a mythical figure said to

have led an army into the Korean peninsula in the 3rd century. A shaman and

powerful warrior, she is often portrayed carrying a sword, a bow and a quiver of arrows.

Japan’s historical rulers were women. Empress Jingû is a mythical figure said to

have led an army into the Korean peninsula in the 3rd century. A shaman and

powerful warrior, she is often portrayed carrying a sword, a bow and a quiver of arrows.

Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865)

Edo (Tokyo)

Woodblock print

Museum no. E.1373-1899」

【 神功皇后と武内宿禰(たけうちのすくね)

《室内装飾の旗(バナー)》シリーズより

1844–62年

1889年の皇室典範が女性の皇位継承を禁じる以前、日本の歴代統治者のうち8名は女性であった。

神功皇后は3世紀に朝鮮半島へ軍を率いたと伝えられる伝説上の人物で、巫女的性格を持つ

強力な女武者として、しばしば剣・弓・矢筒を携えた姿で描かれる。

神功皇后は3世紀に朝鮮半島へ軍を率いたと伝えられる伝説上の人物で、巫女的性格を持つ

強力な女武者として、しばしば剣・弓・矢筒を携えた姿で描かれる。

作者:歌川国貞(1786–1865)

制作地:江戸(東京)

技法:木版画(錦絵)

所蔵番号:E.1373-1899】 「 5. The Actor Iwai Kumesaburō II as Agemaki

1824–25

Beautiful women from the brothel district were a mainstay of prints, drama and

literature; in reality, they worked under exploitative contracts. In the kabuki theatre,

female roles were played by male actors known as onnagata. Here, actorIwai

Kumesaburō II plays the formidable Agemaki of the Miura brothel. Perfecting the

performance of femininity, onnagata set new standards for female beauty.

Some onnagata are recorded as living as women off-stage.

literature; in reality, they worked under exploitative contracts. In the kabuki theatre,

female roles were played by male actors known as onnagata. Here, actorIwai

Kumesaburō II plays the formidable Agemaki of the Miura brothel. Perfecting the

performance of femininity, onnagata set new standards for female beauty.

Some onnagata are recorded as living as women off-stage.

Utagawa Toyoshige (1777–1835)

Edo (Tokyo)

Woodblock Print

Museum no. E.12645-1886」 【 5.二代目 岩井粂三郎の揚巻役

1824–25年

遊郭の美しい女性たちは、版画・演劇・文学において主要な題材となったが、実際には搾取的な

契約の下で働かされていた。歌舞伎では、女性役は女形(おんながた)と呼ばれる男性俳優に

よって演じられた。ここでは、二代目 岩井粂三郎が三浦屋の花魁揚巻を演じている。女形は

女性らしさの演技を完成させることで、新しい「女性美」の基準を作り上げた。中には、舞台を

離れても女性として生活したと記録されている俳優もいた。

契約の下で働かされていた。歌舞伎では、女性役は女形(おんながた)と呼ばれる男性俳優に

よって演じられた。ここでは、二代目 岩井粂三郎が三浦屋の花魁揚巻を演じている。女形は

女性らしさの演技を完成させることで、新しい「女性美」の基準を作り上げた。中には、舞台を

離れても女性として生活したと記録されている俳優もいた。

作者:歌川豊重(1777–1835)

制作地:江戸(東京)

技法:木版画

所蔵番号:E.12645-1886】「 6.Kiso no Oroku Combs, from the series A Compendium of Famous Artisans

1843–47

The story of Oroku of Kiso is an example of filial piety and inventiveness.

Oroku’s familywas poor, but she supported them by making combs out of

a fine-grained local woodwhich, legend says, could cure headaches.

In the Edo period (1615–1868), women from working households often contributed

to the family business. Handmade combs from the Nagano area are still

named after Oroku.

Oroku’s familywas poor, but she supported them by making combs out of

a fine-grained local woodwhich, legend says, could cure headaches.

In the Edo period (1615–1868), women from working households often contributed

to the family business. Handmade combs from the Nagano area are still

named after Oroku.

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858)

Edo (Tokyo)

Woodblock print

Museum no. E.2918-1913」【 6.木曽のお六の櫛

《諸職人尽(しょしょくにんづくし)》シリーズより

1843–47年

木曽のお六の物語は、孝行心と工夫の好例である。お六の家は貧しかったが、彼女は地元産の

きめ細かな木材を用いて櫛を作り、家族を支えた。その櫛は「頭痛を治す」との伝説もあった。

江戸時代(1615–1868)には、働く家庭の女性が家業に従事することも多かった。長野地方の

手作り櫛の中には、今も「お六櫛」と呼ばれるものがある。

きめ細かな木材を用いて櫛を作り、家族を支えた。その櫛は「頭痛を治す」との伝説もあった。

江戸時代(1615–1868)には、働く家庭の女性が家業に従事することも多かった。長野地方の

手作り櫛の中には、今も「お六櫛」と呼ばれるものがある。

作者:歌川広重(1797–1858)

制作地:江戸(東京)

技法:木版画

所蔵番号:E.2918-1913】「 7. The manifestation of Benzaiten overwhelming Taira no Kiyomori at Miyajima

1862

Japan’s two major religions, Shintō and Buddhism, incorporate several female deities.

Benzaiten is associated with water, music and eloquence, and is one of the Seven

Godsof Good Fortune. This print shows her appearing to the 12th-century military

leader Taira no Kiyomori. Kiyomori attributed his success in battle to Benzaiten and

built a temple in her honour.

Benzaiten is associated with water, music and eloquence, and is one of the Seven

Godsof Good Fortune. This print shows her appearing to the 12th-century military

leader Taira no Kiyomori. Kiyomori attributed his success in battle to Benzaiten and

built a temple in her honour.

Utagawa Yoshitora (active 1830–80)

Edo (Tokyo)

Woodblock print

Museum no. E.13975-1886」【 7.厳島における弁才天の顕現が平清盛を圧倒する図

1862年

日本の二大宗教である神道と仏教には、複数の女神が取り込まれている。弁才天(弁財天)は

水・音楽・弁舌に結びつけられ、七福神の一柱でもある。この版画は、12世紀の軍事的指導者

平清盛の前に弁才天が現れる場面を描く。清盛は戦での勝利を弁才天の加護と信じ、彼女を

祀るために寺を建立した。

水・音楽・弁舌に結びつけられ、七福神の一柱でもある。この版画は、12世紀の軍事的指導者

平清盛の前に弁才天が現れる場面を描く。清盛は戦での勝利を弁才天の加護と信じ、彼女を

祀るために寺を建立した。

作者:歌川芳虎(1830–80年頃 活動)

制作地:江戸(東京)

技法:木版画

所蔵番号:E.13975-1886】

7.厳島における弁才天の顕現が平清盛を圧倒する図

V&A日本展示室(Room 45, Toshiba Gallery of Japanese Art) の一角、浮世絵コーナー

とは別のガラスケースを振り返って。

左側 上段

・蒔絵の小箪笥(黒漆に金蒔絵)

・兜(武具の一部、脇に十字架が見えるため「南蛮兜」=キリスト教受容期の影響を示す可能性)

左側 下段

・蒔絵の箱(文箱か手箱)

・日本刀(鞘入り、拵え付)

中央〜右側 上段

・染付磁器の壺(有田・伊万里焼様式、藍色と赤絵の彩色)

・大皿(色絵磁器で人物図)

中央 下段

・壺型の磁器(肥前磁器)

・小型の磁器人形(狛犬のような形)

・小皿類

「日本の陶磁器・漆工芸の国際交流」 をテーマにした展示で、江戸期の肥前磁器

(伊万里焼・柿右衛門様式など)を中心に、西洋輸出向けの豪華な大皿・壺を紹介。

・中央

・大きな色絵大皿(鮮やかな瑠璃地に金彩、中央に人物図、周囲に唐草や花文様)

→ 有田や伊万里の大皿で、17世紀後半~18世紀輸出磁器の典型。ヨーロッパ向けの

華やかな装飾様式。

華やかな装飾様式。

・左側

・染付や色絵の壺類

・着物(黄色地に文様)もケース内に一部展示されているように見えます。

・右側

・青地に赤・金で装飾された壺(花瓶)数点

・その下には小さな器群

ウォーターフォール・オン・カラーズ(水の色彩滝) 千住博 。

・千住博の代名詞である「滝」シリーズのひとつ。

・通常の墨色や単色の滝図とは異なり、多彩な縦色帯が滝となって流れ落ちるように描かれている。

・ラベル解説にあったように、コロナ禍の隔離生活中、庭に刻々と変化する色彩を希望の象徴

として捉えた経験が反映されている。

として捉えた経験が反映されている。

・滝の裏側から外を眺めたような感覚を意図しており、自然の力強さと人間の内的感情が

重ね合わされている。

重ね合わされている。

・江戸時代の浮世絵・工芸と並べて展示されることで、日本美術が古代から現代まで「自然」を

核心に据え続けてきたことを強調している。

核心に据え続けてきたことを強調している。

「 Waterfall on Colors

2023

Often monumental in scale, Hiroshi Senju’s paintings embrace the overwhelming power

of nature. During the Covid-19 pandemic, when Senju was in isolation at his home

in New York, he found hope in the constantly changing colours of his garden.

The vibrant hues in this work represent a landscape as seen from behind a waterfall.

of nature. During the Covid-19 pandemic, when Senju was in isolation at his home

in New York, he found hope in the constantly changing colours of his garden.

The vibrant hues in this work represent a landscape as seen from behind a waterfall.

Hiroshi Senju (born 1958)

New York, United States

Colours on paper

Museum no. FE.69-2023」 【 ウォーターフォール・オン・カラーズ(水の色彩滝)

2023年

平面でありながらしばしば記念碑的な規模を持つ千住博の絵画は、自然の圧倒的な力を抱擁する

ものである。新型コロナウイルスのパンデミックの際、ニューヨークの自宅で隔離生活を

送っていた千住は、庭に絶えず変化する色彩に希望を見いだした。本作における鮮やかな色彩は、

滝の裏側から眺めた風景を表現している。

ものである。新型コロナウイルスのパンデミックの際、ニューヨークの自宅で隔離生活を

送っていた千住は、庭に絶えず変化する色彩に希望を見いだした。本作における鮮やかな色彩は、

滝の裏側から眺めた風景を表現している。

作家:千住博(1958年生)

制作地:アメリカ合衆国 ニューヨーク

技法:紙に彩色

所蔵番号:FE.69-2023】

再び 「根付(netsuke)、印籠(inrō)、小型漆器」などの展示コーナー を。

展示内容の特徴

・左側の棚

・小型の根付(netsuke)が多数並んでいる。材質は象牙・木・漆・磁器など多様で、

江戸時代の装身具として作られたもの。

江戸時代の装身具として作られたもの。

・中央の展示台

・印籠(inrō)と緒締め(ojime)、それに付属する根付が組み合わせて展示されている。

・中央下には大型の漆工芸品(蒔絵の箱)が見える。

・右側の棚

・さらに数多くの根付コレクションが並ぶ。動物・人物・神話モチーフなど。

根付 (netsuke) コレクション に近づいて。

・材質:象牙、木彫、漆塗り、陶磁器など多様。

・形態:

・動物(犬・鼠・兎・鳥など)

・人物(七福神風、力士や僧形)

・神話・民話モチーフ(鬼、霊獣)

・抽象的な小形意匠

根付は 印籠や煙草入れを帯から吊るすための留め具

として17世紀から発展。江戸時代後期には、

実用品であると同時に 高度な彫刻芸術に進化し、武士から町人まで愛好された。

実用品であると同時に 高度な彫刻芸術に進化し、武士から町人まで愛好された。

19世紀後半、ヨーロッパやアメリカでも「小さな彫刻」として収集熱が高まり、

V&Aにも 多数が収蔵 された。

V&Aにも 多数が収蔵 された。

V&Aの所蔵点数は数百点規模

におよび、代表的な作例がこのようにまとめて展示されている と。

「 Netsuke

Traditional forms of Japanese dress such as the kimono did not have pockets. A man would carry everyday items in containers suspended on silk cords fromthe sash (obi) around his waist. The arrangement was held in place by a toggle known as a netsuke. Netsuke were an ideal medium for inventive decoration and developed into miniature works of art. Most of the netsuke displayed here weremade between 1700 and 1870.」

【 根付(ねつけ)

着物などの伝統的な日本の衣服には、ポケットがなかった。そのため男性は日用品を容器に入れ、

腰に巻いた帯(おび)から絹の紐で吊り下げて持ち歩いた。この吊り下げの仕組みを支えた

留め具が根付である。

根付は創造的な装飾表現の媒体として理想的であり、やがて小さな美術作品へと発展した。腰に巻いた帯(おび)から絹の紐で吊り下げて持ち歩いた。この吊り下げの仕組みを支えた

留め具が根付である。

ここに展示されている根付の大半は、1700年から1870年の間に制作されたものである。】

なんとか解読できました。

根付と一緒に展示される 印籠(inrō)とその付属品(緒締め・根付) 👈️リンク のコーナー。

「 Smoking

Tobacco was introduced to Japan by the Portuguese in the late 16th century.

Despite attempts to ban it, smoking became popular among both men and women.

Men carried personal smoking sets consisting of a tobacco container, a pipe and

a pipe-holder. These were hung from the waist and held in place by toggles called

netsuke. Both men and women used communal smoking cabinets, which were usually

made from decorated lacquer. These incorporated small braziersfor burning charcoal

with which to light the pipe.」

【 喫煙

たばこは16世紀後期、ポルトガル人によって日本にもたらされた。禁止の試みがあったにも

かかわらず、喫煙は男女ともに広まった。

かかわらず、喫煙は男女ともに広まった。

男性は、たばこ入れ・煙管(きせる)・煙管筒からなる個人用喫煙具を持ち歩いた。これらは

腰から吊り下げられ、根付(netsuke)と呼ばれる留め具で固定された。

また男女ともに、漆塗りで装飾された共用の喫煙棚(喫煙キャビネット)を使用した。腰から吊り下げられ、根付(netsuke)と呼ばれる留め具で固定された。

そこには小型の火鉢が組み込まれており、炭を焚いて煙管に火を点けることができた。】

根付(netsuke)展示ケース の全景。

・4段の棚に配置され、合計30点以上の根付が並んでいる。

・素材は象牙・木彫・漆など多彩。

・上段には細密な象牙彫刻(群像・龍など)や動物形。

・下段には黒っぽい木彫の人物や面形。

「 Netsuke

Traditional forms of Japanese dress such as the kimono did not have pockets.

A man would carry everyday items in containers suspended on silk cords from

the sash (obi) around his waist. The arrangement was held in place by a toggle known

as a netsuke. Netsuke were an ideal medium for inventive decoration anddeveloped into miniature works of art. Most of the netsuke displayed here weremade between

1700 and 1870.」

A man would carry everyday items in containers suspended on silk cords from

the sash (obi) around his waist. The arrangement was held in place by a toggle known

as a netsuke. Netsuke were an ideal medium for inventive decoration anddeveloped into miniature works of art. Most of the netsuke displayed here weremade between

1700 and 1870.」

【 根付(ねつけ)

着物など日本の伝統的な衣服にはポケットがなかった。男性は日用品を容器に入れ、

帯(おび)から絹の紐で吊るして持ち歩いた。この仕組みを支える留め具が「根付」である。

根付は創意工夫を凝らした装飾の媒体として理想的であり、やがて小さな美術品として発展した。帯(おび)から絹の紐で吊るして持ち歩いた。この仕組みを支える留め具が「根付」である。

ここに展示されている根付の大部分は 1700年から1870年の間に制作されたものである。】

着物・衣装コーナー を再び。

・左:

・現代的な意匠の浴衣/着物。大きなドットや幾何学模様をパッチワーク的に配置した

デザイン。おそらく戦後以降の「モダン着物」か現代アーティストによる作品。

デザイン。おそらく戦後以降の「モダン着物」か現代アーティストによる作品。

・中央:

・黒または濃茶色の羽織/外套。絹地に無地あるいは渋い文様。実用的な装いか、儀礼用。

・右:

・茶系の地に虎の刺繍(または友禅染)が大きく入った豪華な打掛または能装束。

力強い図柄から、武家や芝居に関わる衣裳である可能性。

力強い図柄から、武家や芝居に関わる衣裳である可能性。

「 Kimono for Men

The kimono is a garment worn by both men and women. Although sleeve length varies,

the basic shape is the same. From the 17th century, male dress was characterised

by dark colours and subdued patterns. Yet restrained exteriors often hid flamboyant

linings and under-kimono, a fashion that continued into the 20th century.

Today, few men in Japan wear kimono, but in recent years there has been a revival.

More and more designers cater for this growing market, giving kimono for men

renewed style and panache.」

【 男性用の着物

the basic shape is the same. From the 17th century, male dress was characterised

by dark colours and subdued patterns. Yet restrained exteriors often hid flamboyant

linings and under-kimono, a fashion that continued into the 20th century.

Today, few men in Japan wear kimono, but in recent years there has been a revival.

More and more designers cater for this growing market, giving kimono for men

renewed style and panache.」

【 男性用の着物

着物は男女ともに着用する衣服である。袖の長さには違いがあるが、基本的な形は同じである。

17世紀以降、男性の着物は暗い色調や落ち着いた文様が特徴となった。だが、その控えめな

外観の下には、華やかな裏地や襦袢(下着の着物)を隠すことが多く、このファッションは

20世紀まで続いた。

外観の下には、華やかな裏地や襦袢(下着の着物)を隠すことが多く、このファッションは

20世紀まで続いた。

現代では着物を着る男性は日本では少なくなったが、近年は復興の兆しが見られる。ますます

多くのデザイナーがこの成長市場に注目し、男性用の着物に新たなスタイルと華やかさを

与えている。】

多くのデザイナーがこの成長市場に注目し、男性用の着物に新たなスタイルと華やかさを

与えている。】

「 MODERN & CONTEMPORARY(現代日本美術) 」展示コーナー。

極彩色の現代陶芸作品 をアップで。 Heart on Wave 川合 一仁。

「 Studio Crafts

Today, many Japanese makers use traditional craft media to create unique works of art.

They are supported by an extensive system of art colleges and a well-developed art

market in Japan. Numerous craft associations also encourage their activities, as do

regular competitive exhibitions. All the objects have been made since 2010, many of

them very recently.」

【スタジオ・クラフト(現代工芸)

今日、多くの日本の作り手は、伝統的な工芸の素材や技法を用いて、独自の芸術作品を創り

出している。彼らの活動は、日本の充実した美術大学の制度や発達した美術市場によって

支えられている。また、数多くの工芸団体がその活動を奨励しており、定期的に行われる

公募展や競技的な展覧会も後押しとなっている。ここに展示されている作品はすべて

2010年以降に制作されたもので、多くはごく最近のものである。】

「 1. ‘Heart on Wave’

2023

Kawai Kazuhito uses clay to express his nostalgia for 1980s Japan. After an initial

biscuit firing, he painstakingly applies dots of glaze to his sculptures to blurthe

boundaries between reality and illusion. The porcelain figurine of Ariel from

The Little Mermaid at the top refers to Tokyo Disneyland’s opening in 1983.

It was the first Disneyland outside the United States and symbolises Japan’s economic prominence during Kawai’s childhood.

biscuit firing, he painstakingly applies dots of glaze to his sculptures to blurthe

boundaries between reality and illusion. The porcelain figurine of Ariel from

The Little Mermaid at the top refers to Tokyo Disneyland’s opening in 1983.

It was the first Disneyland outside the United States and symbolises Japan’s economic prominence during Kawai’s childhood.

Kawai Kazuhito (born 1984)

Kasama, Ibaraki prefecture

Glazed stoneware, with a porcelain figure

Given by Hiroyuki Maki / Buffalo Inc.

Museum no. FE.61-2024」 【1. Heart on Wave(波の上の心)

2023年

川合一仁(かわい かずひと)は、1980年代日本への郷愁を粘土で表現している。素焼きの後、

彼は現実と幻想の境界を曖昧にするために、丹念に釉薬の点を彫刻表面に施す。作品上部

にある『リトル・マーメイド』のアリエルの磁器人形は、1983年に開園した

東京ディズニーランドを示唆している。それは米国以外で初めてのディズニーランドであり、

川合の幼少期における日本の経済的繁栄を象徴している。

川合 一仁(1984年生)

茨城県笠間市

釉薬を施した炻器、

磁器製人形付き寄贈:牧浩之/Buffalo Inc.

所蔵番号:FE.61-2024】

こちらも「MODERN & CONTEMPORARY(現代・現代美術)」セクション。

木工によるデザイン作品(おそらく屏風風の木製パネルや円形構造物) コーナー。

中央に展示されているのは、木工によるデザイン作品(おそらく屏風風の木製パネルや

円形構造物)で、横には椅子や織物、籠などが並んでいた。

・中央の作品:格子状の木製パネルと円形の木工フレーム。伝統的な木工技法を使いながら、

現代的な抽象オブジェとして再構成されたもの。

現代的な抽象オブジェとして再構成されたもの。

・右側:シンプルな椅子や織物(黒布)など、生活とアートの境界を意識した現代工芸。

・左側:陶器・籠・白い紙造形など、素材ごとにまとめられた展示。

メモリー 熊井恭子 。

「 Studio Crafts

Today, many Japanese makers use traditional craft media to create unique works of art.

They are supported by an extensive system of art colleges and a well-developed art

market in Japan. Numerous craft associations also encourage their activities,

as do regular competitive exhibitions.」

They are supported by an extensive system of art colleges and a well-developed art

market in Japan. Numerous craft associations also encourage their activities,

as do regular competitive exhibitions.」

【 スタジオ工芸

今日、多くの日本の作家たちは、伝統的な工芸の媒体を用いて独自の美術作品を制作しています。

彼らは、日本における広範な美術大学の制度や発達した美術市場によって支えられています。

多くの工芸協会もまたその活動を奨励しており、定期的な競技的展覧会もそれを後押しして

います。】

彼らは、日本における広範な美術大学の制度や発達した美術市場によって支えられています。

多くの工芸協会もまたその活動を奨励しており、定期的な競技的展覧会もそれを後押しして

います。】

「1. 'Memory'2017Kumai Kyoko is an internationally recognised fibre artist.

She created this work in remembrance of the Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami of

2011, which caused over 15,000 deaths. Kumai works mainly with stainless steel wire.

Here she has shapedthe wire into a bundle of organic forms. These represent people’s

feelings about the unforgettable disaster that has had a lasting impact in Japan.

Kumai Kyoko (born 1943)

Tokyo

Stainless steel wire

Given anonymously

Museum no. FE.57-2023」

【1. メモリー2017年熊井恭子は国際的に認められたファイバー・アーティストです。

彼女は2011年の東北大震災と津波(死者15,000人以上)を追悼して、この作品を

制作しました。熊井は主にステンレススチールワイヤーを用いて制作を行います。

ここではワイヤーを有機的な形態の束に組み上げ、それを通じて日本に長く影響を残した

忘れがたい災害に対する人々の感情を表現しています。

熊井恭子(1943年生まれ)

東京

素材:ステンレススチールワイヤー

寄贈:匿名寄贈

館蔵番号:FE.57-2023】

「民芸・復興(Discovery and Revival)」セクションの一部で、柳宗悦の民芸運動の文脈で

紹介されている作品群。

手前の陶磁器・漆器

・左:漆塗りの小箪笥(収納箱)

・中央:緑釉鉢・黒釉壺

・右:青磁花瓶・染付小壺

・これらはいずれも江戸~近代にかけての実用品で、民芸運動では「無名の職人による

日常の器こそ美しい」と再評価されました。

日常の器こそ美しい」と再評価されました。

藍染の幕(のれん/幔幕の類) で、流水に菊の花、さらに上部に家紋が配された文様 。

「 Discovery and Revival

An interest in folk crafts arose in Japan in the early 20th century as a reaction to rapid industrialisation and urbanisation. Still active today, the Japanese Folk Craftmovement

was established in 1926 by the critic and theorist Yanagi Soetsu. He and his followers

collected historical folk crafts and founded museums in whichto show them.

They also encouraged the preservation of traditional craft techniquesand the making of contemporary work in the style and spirit of historical models.」

【 発見と復興

20世紀初頭、日本では急速な工業化と都市化への反動として、民芸(フォーククラフト)への

関心が高まりました。現在も活動が続いている日本民芸運動は、1926年に批評家で理論家の

柳宗悦によって設立されました。柳とその仲間たちは歴史的な民芸品を収集し、それらを

展示するための博物館を設立しました。また、伝統的な工芸技術の保存と、歴史的な様式と

精神に基づいた現代作品の制作を奨励しました。】

「 5. Bedding cover

1850–1900

The traditional Japanese form of bedding is the futon, which comprises a mattressand

a cover laid out on the floor. The cover is often decorated. This boldly patterned

example was probably part of a bride’s trousseau. It reveals how subtle shading

canbe achieved using only one colour. Careful mending is evidence of how greatly

suchtextiles were treasured.

a cover laid out on the floor. The cover is often decorated. This boldly patterned

example was probably part of a bride’s trousseau. It reveals how subtle shading

canbe achieved using only one colour. Careful mending is evidence of how greatly

suchtextiles were treasured.

Cotton with freehand paste-resist dyeing (tsutsugaki)

Museum no. T.331-1960」【 5. 布団カバー

1850~1900年

日本の伝統的な寝具の形は布団であり、床の上に敷かれる敷布団と掛け布団から構成されて

います。掛け布団のカバーはしばしば装飾が施されます。この大胆な文様の例は、おそらく

花嫁の嫁入り道具の一部であったと考えられます。ここでは、1色だけを用いても微妙な

濃淡表現が可能であることが示されています。丁寧に施された繕いは、このような織物が

どれほど大切に扱われていたかを物語っています。

います。掛け布団のカバーはしばしば装飾が施されます。この大胆な文様の例は、おそらく

花嫁の嫁入り道具の一部であったと考えられます。ここでは、1色だけを用いても微妙な

濃淡表現が可能であることが示されています。丁寧に施された繕いは、このような織物が

どれほど大切に扱われていたかを物語っています。

素材:木綿、筒描きによる防染染色

館蔵番号:T.331-1960】

伊万里焼・柿右衛門様式を中心とした日本磁器(17~18世紀) 。

特に ヨーロッパに輸出された伊万里焼や柿右衛門様式のコレクションが多く展示 されている と。

・上段中央の壺:

色絵(赤・緑・青)で花鳥が描かれた柿右衛門様式の磁器。ヨーロッパで

特に人気が高かったスタイル。

特に人気が高かったスタイル。

・上段左右の壺:

藍一色で描かれた染付(sometsuke)、竹や花などの文様。

・中段中央の大皿:

色絵伊万里。赤・青・金を用いた豪華な意匠で、オランダ東インド会社を

通じてヨーロッパへ輸出されたもの。

通じてヨーロッパへ輸出されたもの。

・中段右の像:

獅子または象の置物(伊万里の輸出向け磁器)。ヨーロッパで装飾品として

人気を博した。

人気を博した。

・下段の皿類:

いずれも染付や色絵の伊万里磁器。文様は唐草や人物図、風景など。

「 Porcelain for Europe

Porcelain was first made in Japan in the early 17th century at kilns in and around

the town of Arita. The earliest pieces were designed for the domestic market.

In 1644,following the fall of the Ming dynasty, Chinese porcelain became temporarily

unavailable and the Dutch turned to Japan as an alternative source for this

highlysought-after commodity. Japan increased its output of porcelain, with much of

it being aimed at the export market and often made in shapes copying

Europeanceramics.」

【 ヨーロッパ向けの磁器 日本で磁器が初めて作られたのは17世紀初頭、有田の町およびその

周辺の窯においてでした。最初の作品は国内市場向けにデザインされていました。

1644年、明王朝の滅亡に伴い、中国磁器が一時的に入手できなくなると、オランダ人はこの

需要の高い商品を得るために日本を代替供給地としました。日本は磁器の生産量を増加させ、

その多くを輸出市場に向け、しばしばヨーロッパの陶磁器の形を模した作品を作りました。】

「 南蛮貿易・キリシタン関連展示

」の一部。

展示内容(上段)

1.螺鈿細工の小箪笥(cabinet with drawers)

漆塗りに螺鈿や金粉を施した豪華な小型箪笥。ヨーロッパへの輸出品として特に人気が

ありました。

ありました。

2.十字架(Christian cross)

キリスト教が16世紀に日本へ伝来した証拠の一つ。隠れキリシタンが所持していた可能性が

あります。

あります。

3.南蛮兜(nanban kabuto)

ヨーロッパの兜を模した日本製の甲冑。安土桃山時代に西洋甲冑の影響を受けて制作

されました。

されました。

展示内容(下段)

4.蒔絵の箱(lacquer chest/box)

蒔絵技法による装飾箱。西洋の修道院や貴族の館でも保存され、装飾芸術として高く評価

されました。

されました。

5.火縄銃(hinawajū / matchlock gun)

1543年、ポルトガル人によって種子島に伝来。日本で大量生産され戦国時代の戦術を変革

しました。

しました。

6.刀剣(sword with European-style hilt)

柄や鍔に西洋風の装飾が施された刀。南蛮貿易期にヨーロッパとの交流を示す作品。】

「 Europe in Japan The first Europeans to reach Japan were the Portuguese. Arriving in

the early 1540s, they brought with them guns and Christianity. The latter ultimately

proved unwelcome. Christianity was banned and the Portuguese were expelled.

From 1639 the Dutch were the only Europeans permitted to trade with Japan.

They were kept under close scrutinyon Dejima, an artificial island in Nagasaki Bay.

Despite the restrictions placed on the Dutch, the goods and scientific knowledge

they brought with them werethe subject of both scholarly enquiry and popular interest.」

【 日本におけるヨーロッパ 日本に最初に到達したヨーロッパ人はポルトガル人でした。

1540年代初頭に到来し、鉄砲とキリスト教をもたらしました。しかし後者(キリスト教)は

最終的に歓迎されず、禁教とともにポルトガル人は追放されました。1639年以降、日本と交易を

許された唯一のヨーロッパ人はオランダ人だけとなりました。彼らは長崎湾の人工島・出島に

厳重な監視のもとで滞在しました。制限が課されていたにもかかわらず、オランダ人が

もたらした商品や科学的知識は、学問的探求や一般の関心の対象となりました。】

これは「南蛮漆器(Nanban lacquerware)」の 代表的な輸出用大型箱(coffer / chest) 。「 Kamaboko(蒲鉾型) 」のドーム状蓋をもつ大型キャビネット。

・南蛮漆器は16〜17世紀、日本で欧州輸出を目的として作られた漆工芸品。「Nanban」または 「Namban」と呼ばれます。

・輸出先に欧州貴族や宣教師が含まれ、キリスト教用具(十字架箱など)や豪華な装飾箱として

使われた例も多い。

使われた例も多い。

・技法としては、漆(urushi)を塗った上で蒔絵(maki-e:金銀粉などを散らす技法)、

螺鈿(raden:貝殻象嵌)、金銀装飾を組み合わせたもの。

螺鈿(raden:貝殻象嵌)、金銀装飾を組み合わせたもの。

・形状として、「ドーム状/丸みを帯びた蓋」「箱体」「金属の金具・鍵・取っ手」などを

備えているものが多い。壁掛けではなく、家具・収納箱としての用途。

備えているものが多い。壁掛けではなく、家具・収納箱としての用途。

「 Lacquer for Europe

When the Europeans came to Japan in the mid-1500s, they were immediately

by the lustre and decorative brilliance of objects made from lacquer (urushi).

The Japanese soon began to produce lacquer items for export copying European

shapes. Early pieces were decorated in mother-of-pearl using techniques similar

to those found in China, Korea and India. Export lacquer from the 1600s onwards

was decorated primarily in gold on black, and featured elaborate pictorial schemes.」

【 ヨーロッパ向けの漆器

1500年代半ばにヨーロッパ人が日本に来航したとき、彼らはすぐに漆(うるし)で作られた

器物の光沢と装飾的な華やかさに魅了されました。やがて日本人はヨーロッパの器物の形を

写した輸出用漆器を生産するようになります。初期の作品は螺鈿(らでん)で装飾され、

中国・朝鮮・インドで見られる技法と類似していました。1600年代以降の輸出漆器は、

黒地に金を主体とした装飾が施され、精緻な絵画的意匠が特徴となりました。】

「 1. The Mazarin Chest

1640–43

This extremely high-quality lacquer chest is one of the most important pieces of Japanese export lacquer ever made. It is recorded as having been shipped toEurope by the Dutch East India Company in 1643. Its first owner was the French statesman and Catholic cardinal Jules Mazarin. The scenes on the front and sides allude to episodes from classical Japanese literature. The landscape on the lid featurestemple buildings and a castle complex.

Probably Kōami workshop

Kyoto

Kyoto

Wood covered in black lacquer with decoration in gold and silver lacquer; silver foil

and mother-of-pearl inlay; details in gold, silver and shibuichi alloy; gilded and

lacqueredmetal fittings; French steel key

Museum no. 412-1882」and mother-of-pearl inlay; details in gold, silver and shibuichi alloy; gilded and

lacqueredmetal fittings; French steel key

【 1. マザラン・チェスト(Mazarin Chest)

1640–43年

この極めて高品質な漆塗りの大形収納箱は、日本の輸出漆器の中でも最も重要な作品の

ひとつです。1643年にオランダ東インド会社によってヨーロッパへ輸送された記録が

残っています。最初の所有者はフランスの政治家でありカトリック枢機卿であったジュール・

マザランでした。前面と側面の場面は日本古典文学のエピソードを示唆しており、蓋の風景

には寺院建築や城郭群が描かれています。

ひとつです。1643年にオランダ東インド会社によってヨーロッパへ輸送された記録が

残っています。最初の所有者はフランスの政治家でありカトリック枢機卿であったジュール・

マザランでした。前面と側面の場面は日本古典文学のエピソードを示唆しており、蓋の風景

には寺院建築や城郭群が描かれています。

おそらく高阿弥(こうあみ)派工房

京都

黒漆塗木地に、金・銀漆による加飾、銀箔・螺鈿象嵌を施す。細部は金・銀・四分一合金

(しぶいち)を使用。金銀蒔絵の金具を付属し、フランス製鉄鍵を伴う。

館蔵番号:412-1882】(しぶいち)を使用。金銀蒔絵の金具を付属し、フランス製鉄鍵を伴う。

・・・ もどる ・・・

・・・ つづく ・・・

お気に入りの記事を「いいね!」で応援しよう

【毎日開催】

15記事にいいね!で1ポイント

10秒滞在

いいね!

--

/

--

© Rakuten Group, Inc.