PR

X

Keyword Search

▼キーワード検索

Comments

私はイスラム教徒です@ Re:アイルランド・ロンドンへの旅(その131): ロンドン散策記・アルバート記念碑(Albert Memorial)-2(11/06)

神神は言った: コーランで 『 (21) 人々…

私はイスラム教徒です@ Re:アイルランド・ロンドンへの旅(その122): ロンドン散策記・Victoria and Albert Museum・ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館-5(10/28)

神神は言った: コーランで 『 (21) 人…

2025年版・岡山大学…

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

【時間が出来れば、… New!

Gママさん

New!

Gママさん

続日本100名城東北の… New! オジン0523さん

ムベの実を開くコツ… noahnoahnoahさん

noahnoahnoahさん

エコハウスにようこそ ecologicianさん

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん

New!

隠居人はせじぃさん【時間が出来れば、…

New!

Gママさん

New!

Gママさん続日本100名城東北の… New! オジン0523さん

ムベの実を開くコツ…

noahnoahnoahさん

noahnoahnoahさんエコハウスにようこそ ecologicianさん

Calendar

カテゴリ: 海外旅行

【

海外旅行 ブログリスト

】👈リンク

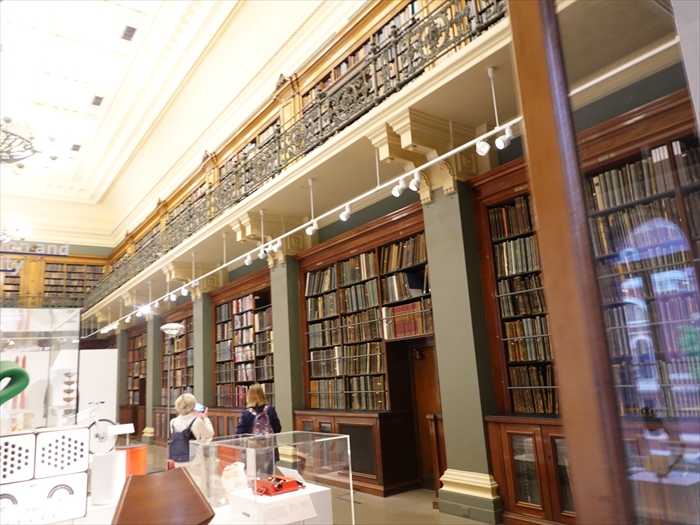

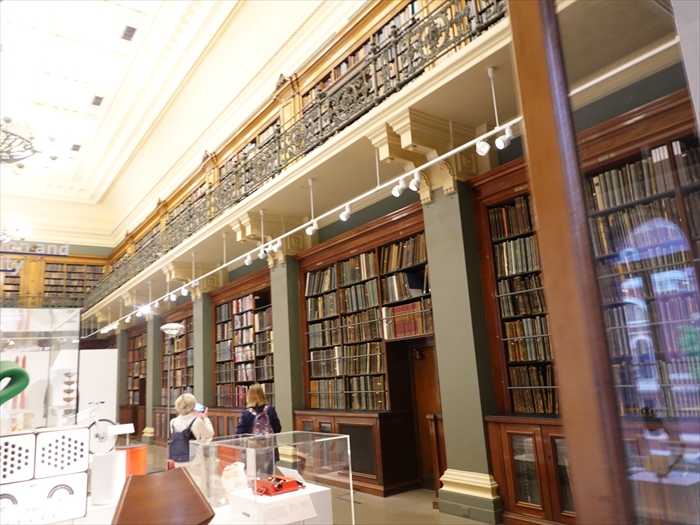

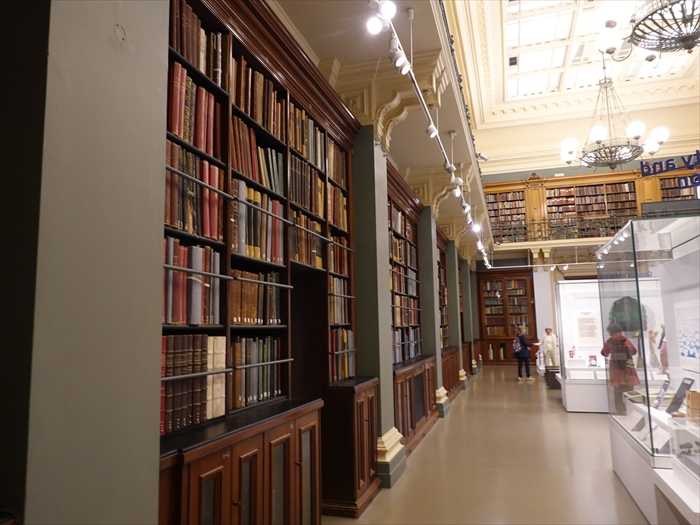

部屋の全景をネットの写真から。

Design 1900–Nowギャラリーの長い通路・Room NO 76 .

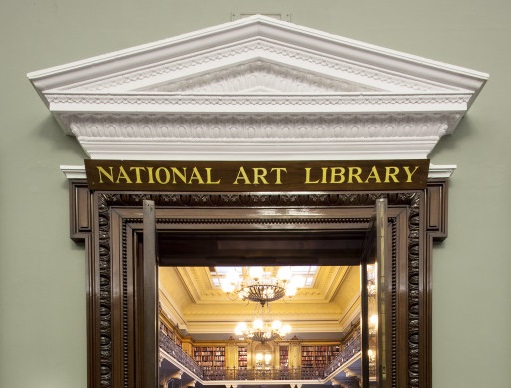

V&A の National Art Library(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー) の書庫 が見える

一角二層吹き抜けに鋳鉄の手すり、壁一面の木製書架、天窓からの採光という内装が決め手。

手前にあるプロダクトの展示ケースは、ギャラリー側の通路に置かれており、ガラス越しに

実際のライブラリーの本棚が見える構成になっていた。

中の書籍は本物で、閲覧は登録制 (閲覧室は別室) とのこと。

・英国随一の装飾美術・デザイン専門図書館。展覧会図録、装飾美術・建築・ファッション・

・書庫はクローズドスタック(直接は取れず、請求して閲覧)。閲覧室の参考棚のみ開架。

利用の基本(実務メモ)

・無料で利用可。ただし資料の閲覧は利用者登録(身分証)が必要。

・事前にオンラインで請求→来館時に閲覧、の流れが標準。

・閲覧室では通常鉛筆のみ使用、飲食不可。資料撮影は可否が分かれるので

係員の指示に従う。

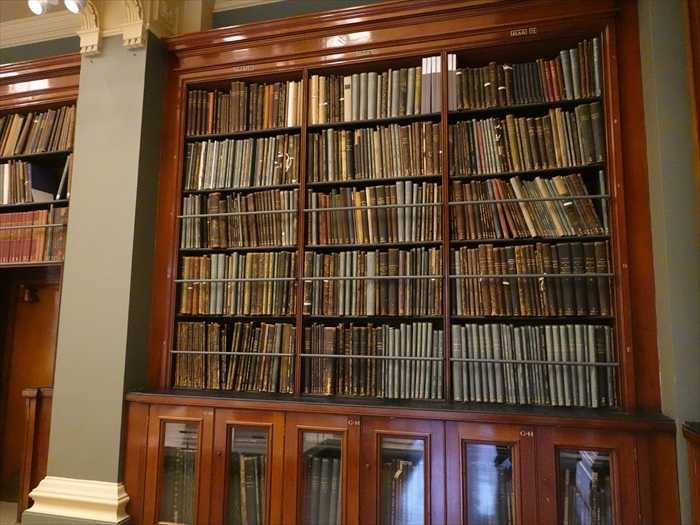

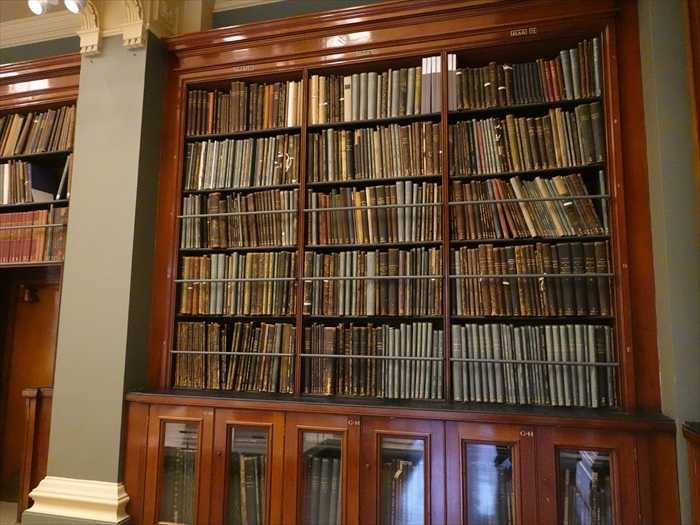

・ 落下防止バー: 各段の前面に通る金属バー。地震・人の動き・清掃時に閲覧ゾーン側への

落下防止&整列保持の役割。

必要に応じて上げ下げして本を出し入れしする と。

・下段のガラス扉 :大型判(フォリオサイズ)の画集・製図集・製本済み雑誌などを収納。

湿度や埃から守るためガラス扉付き と。

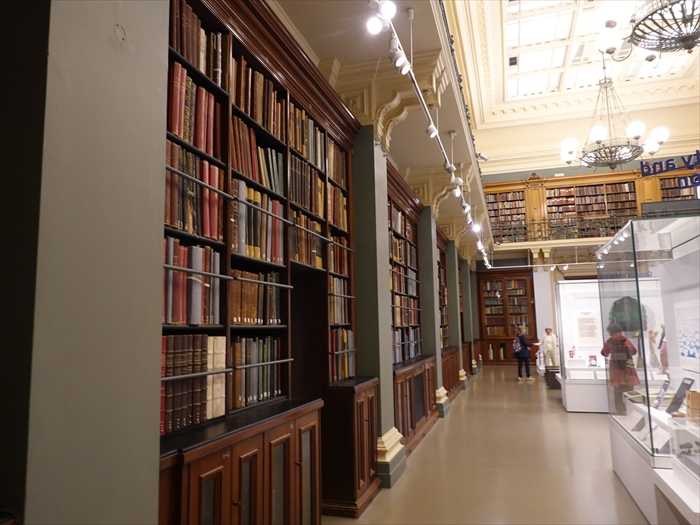

National Art Library(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー)書庫の外壁。

右手の背の高い木製書架は図書館の実物の書庫、左手の白い展示ケースと

“ Sustainability and Subversion ”のサインはデザイン・ギャラリーのテーマ展示の一部。

二層構成になっており、 上階は鋳鉄手すりの回廊、天井からシャンデリア

「Design 1900–Now」ギャラリー通路から見た、National Art Library

(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー)書庫の外壁。

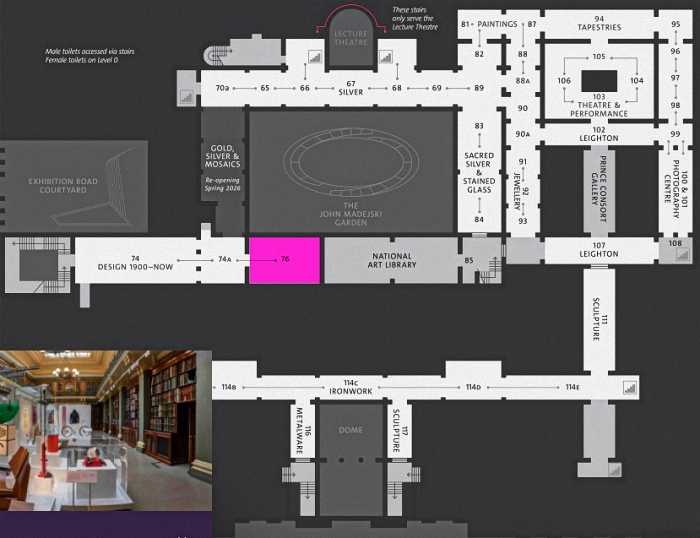

右側:John Madejski Garden

左側:National Art Library(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー)の入口

金文字「NATIONAL ART LIBRARY」扉はこの左壁沿い(写真フレーム外)にあった。

前方:西(Room 74 側)

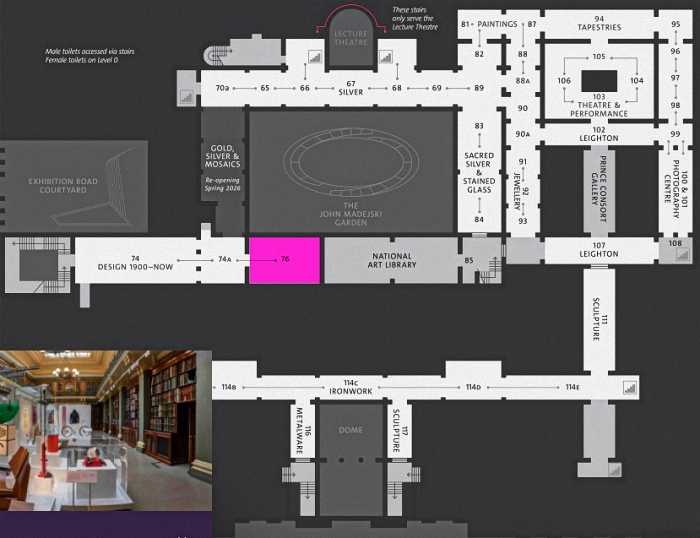

Level2 のMAP。 ■ がRoom NO 76

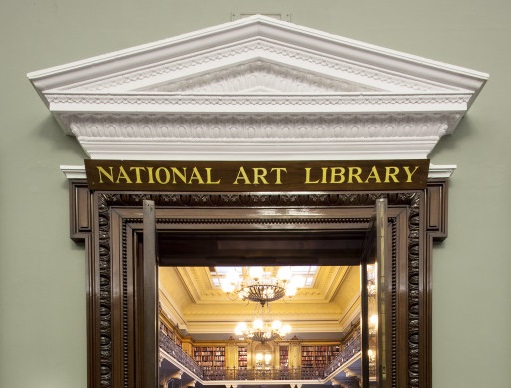

そしてこれが金文字「 NATIONAL ART LIBRARY 」の入口。

近づいて。

Art Library(閲覧室)への入口。

Art Library(閲覧室)内部の写真 。

ズームして。

中庭南辺の通路(Room 76)から東寄り(No.25 付近)の階段/エレベーターで Level 3 へ 上がり 、Rooms 118–125 の表示に従って進む。

V&A の “BRITAIN (1760–1900)”(British Galleries) への案内サイン。

表示の 118–…(~125c など) は該当する部屋番号を示す。

産業革命期からヴィクトリア時代までの英国の家具・銀器・陶磁・室内装飾などを展示。

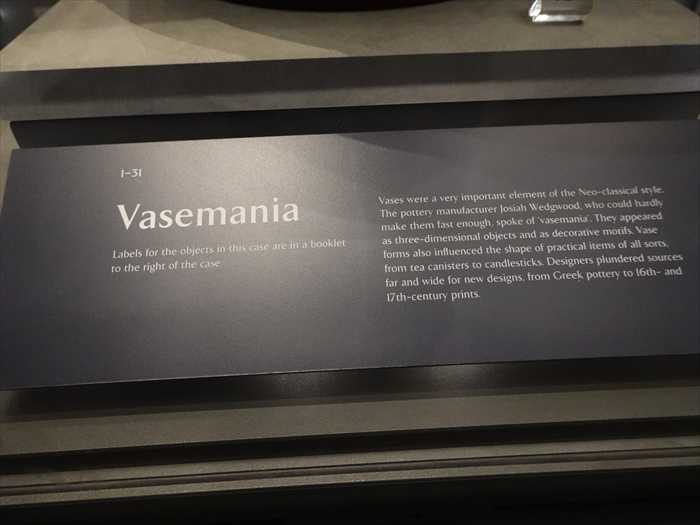

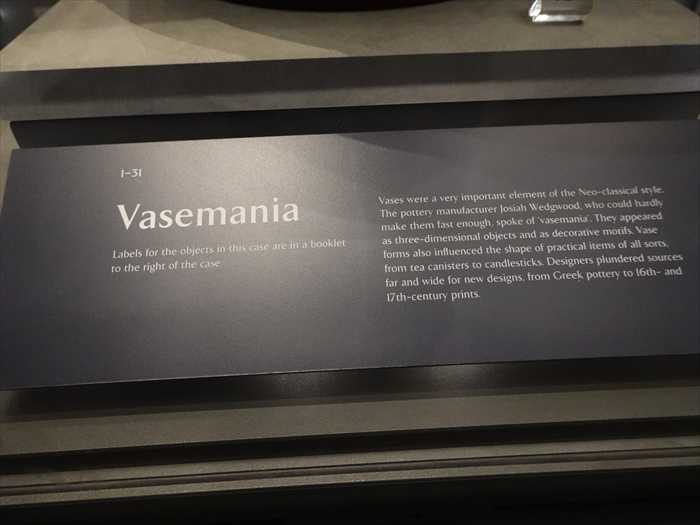

このケースは、V&Aの英国ギャラリーで紹介されている Vasemania(花瓶熱) を一望できる展示。

正面から。

18~19世紀の新古典主義期、古代ギリシャ・ローマの「壺(vase)」の形や装飾が大流行し、

実用品や室内装飾までをも壺風にしてしまった――という現象を、実物で示していたのだ。

「 Vasemania

The pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, who could hardly make them fast enough,

spoke of“vasemania”. They appeared as three-dimensional objects and as decorative

motifs. Vase forms also influenced the shape of practical items of all sorts, from tea

canistersto candlesticks. Designers plundered sources far and wide for new designs,

from Greekpottery to 16th- and 17th-century prints.」

【 ヴェーズマニア

このケース内の各作品ラベルは、ケース右手に置かれた冊子にあります。花瓶は新古典主義様式に

おいて非常に重要な要素でした。

陶磁器メーカーのジョサイア・ウェッジウッドは、需要に追いつけないほどで、この現象を

「ヴェーズマニア」と呼びました。花瓶は立体作品としてだけでなく、装飾モチーフ

としても登場しました。さらに花瓶の形は、茶葉用キャニスターから燭台に至るまで、実用品の

造形にも影響を与えました。デザイナーたちは新しい意匠を求め、ギリシャの陶器から

16~17世紀の版画にいたるまで、広範な資料を貪欲に参照しました。】

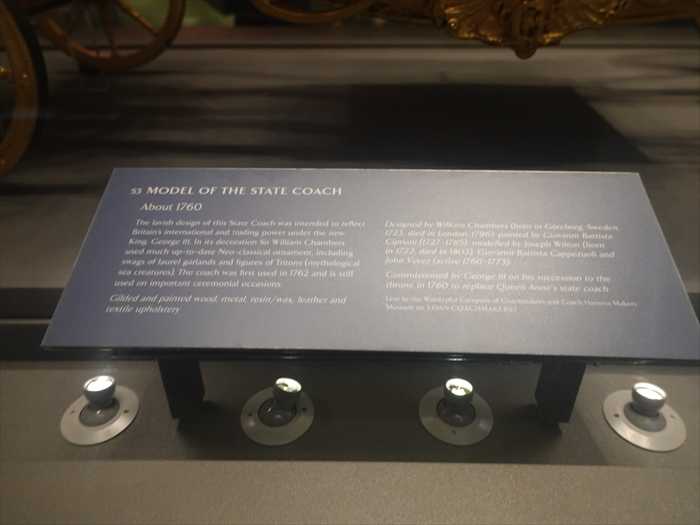

国王のゴールド・ステート・コーチの模型 。

「 53 MODEL OF THE STATE COACH

Museum no. [----]」

【 53 国王のゴールド・ステート・コーチの模型

イギリスの(海上)パワーを表す意図で作られました。建築家ウィリアム・チェンバースの

デザインにより、ジョヴァンニ・バッティスタ・チプリアーニの絵画パネルと、ジョゼフ・

ウィルトンの彫刻が施され、トリトン(海神)などの像が海軍力を象徴しています。

実物のコーチは1762年に完成し、以後も重要な国家儀礼で用いられてきました。】

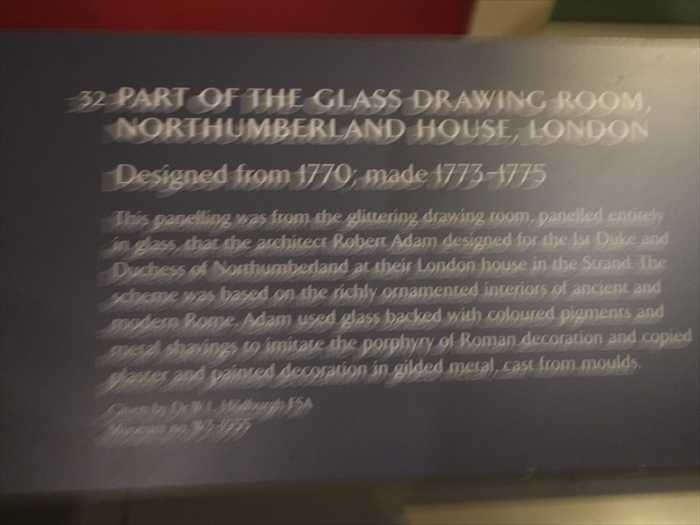

「Britain (1760–1900)」セクションに展示されている部屋の装飾の一部。壁面と扉を含む

豪華なインテリアで、19世紀の英国室内装飾様式を示していた。

「 32 PART OF THE GLASS DRAWING ROOM, NORTHUMBERLAND HOUSE, LONDON

【 32 ガラス張り応接室の一部 ノーサンバーランド・ハウス(ロンドン)

ピア・グラスに取り付けられた祭壇額。

・「ピア・グラス(pier glass)」とは、壁と壁の間(柱=pier の間)に置かれる大型の姿見鏡 を

意味します。しばしば家具調の装飾が施され、室内を豪華に見せる効果がありました。

・この鏡は、先ほどの案内板にあった「ノーサンバーランド・ハウスのガラス張り応接室」の

一連の装飾の一部であり、部屋の豪華さを象徴する重要な要素 と。

・フレームの左右に配置された人物像(天使や寓意像)は、当時流行したネオクラシカル装飾の

典型で、金箔仕上げによって室内照明の輝きをさらに増す役割を果たしました。

「 38 MIRROR

【 38 ピア・グラスに取り付けられた祭壇額

当時イギリスで最も人気のあった建築家の一人、ロバート・アダムのために作られました。

ロンドンのノーサンバーランド・ハウスにある「ガラス張り応接室(Glass Drawing Room)」

用に設計されたものです。】

イギリス・ギャラリー(1760–1900) の展示風景で、18世紀末から19世紀にかけての

「 ファッショナブルな暮らし(Fashionable Living) 」をテーマにした一角。

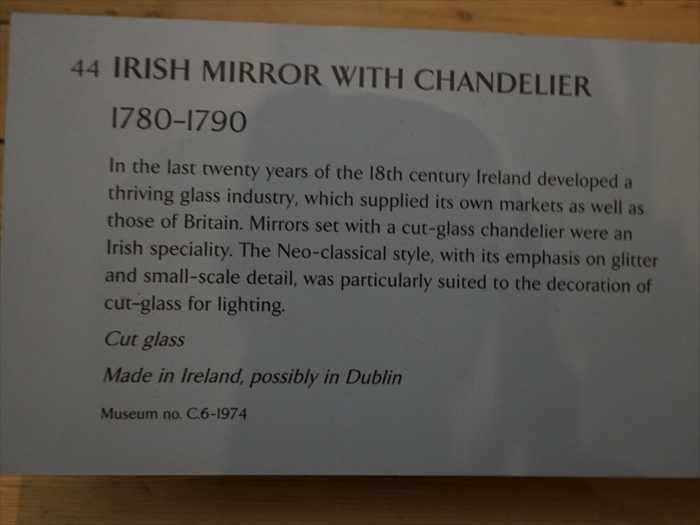

44 IRISH MIRROR WITH CHANDELIER・アイルランド製 鏡付きシャンデリア

「 44 IRISH MIRROR WITH CHANDELIER

Cut glass

【 44 シャンデリア付きアイルランド製鏡

V&A(ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館)「 THE WOLFSON GALLERIES(118) 」 の入口部分。

「 WHAT WAS NEW?

standard forms. These goods could then be exported and sold throughout the world.」

【 新しいものは何か?

ようになり、輸出され、世界中で販売されました。】

作品名:The Campbell Sisters dancing a Waltz

ワルツを踊るキャンベル姉妹 作家:Lorenzo Bartolini(1777–1850、イタリア) 。

「 FASHIONABLE LIVING

style, developed, aimed at the decoration of fashionable domestic interiors.

In Britain, the leading sculptor was Antonio Canova’s pupil, Antonio d’Este,

who produced idealised marble sculptures of mythological subjects.」

【 ファッショナブルな暮らし

V&A(ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館)の ブリティッシュ・ギャラリー の一室。

British Galleries 1500–1900 の「19世紀室内装飾」展示 の一部。

Spode(スポード窯)のディナーサービス (約1820年)。

「 PART OF A DINNER SERVICE

Porcelain

Made by the Spode Factory, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire」

【 ディナーサービスの一部

「The Wolfson Galleries(ウォルフソン・ギャラリー)」の一部で、18世紀末〜19世紀

初頭の室内装飾と家具 を再現するようなセクション。

写真中央には 大きな円形の凸面鏡(Convex Mirror, 約1790年) が掲げられています。

鏡は金箔仕上げの松材フレームに収められ、上下にアカンサスの葉飾りや鷲のモチーフが

加えられている。これは当時の流行で、家具デザイン集(George Smith, 1808年刊)でも

紹介された様式。

「 19 CONVEX MIRROR

【 19 凸面鏡

左側の肖像画

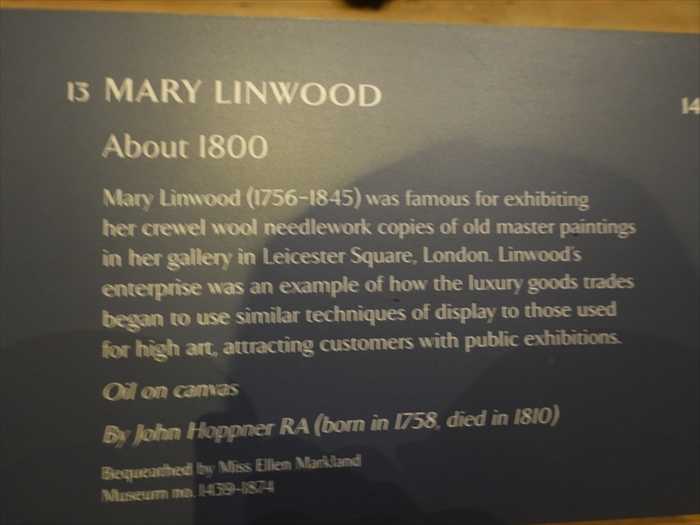

「 13 MARY LINWOOD

【 13 メアリー・リンウッド

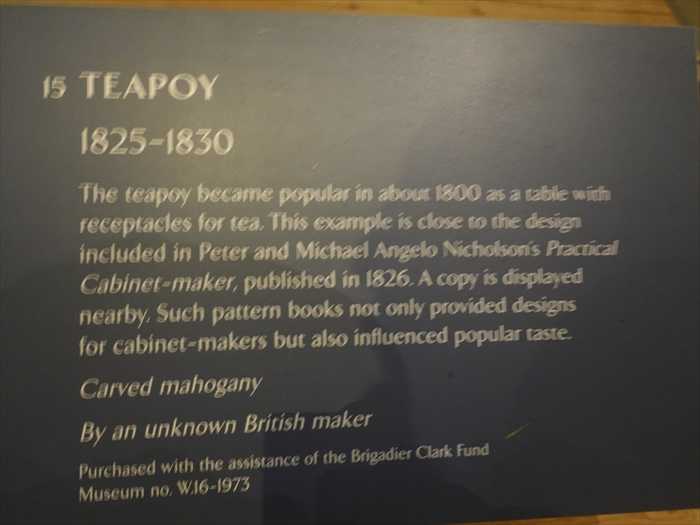

「TEAPOY

The teapoy became popular in about 1800 as a table with receptacles for tea.

This example is close to the design included in Peter and Michael Angelo Nicholson’s

Practical Cabinet-maker, published in 1826. A copy is displayed nearby. Such pattern

books not only provided designs for cabinet-makers but also influenced popular taste.

Carved mahogany

By an unknown British maker

Purchased with the assistance of the Brigadier Clark Fund

Museum no. W.16-1973」

【 15 ティーポイ(茶卓)

レディ・アン・ハミルトン ・ Lady Anne Hamilton (1766–1846) 👈️リンク。

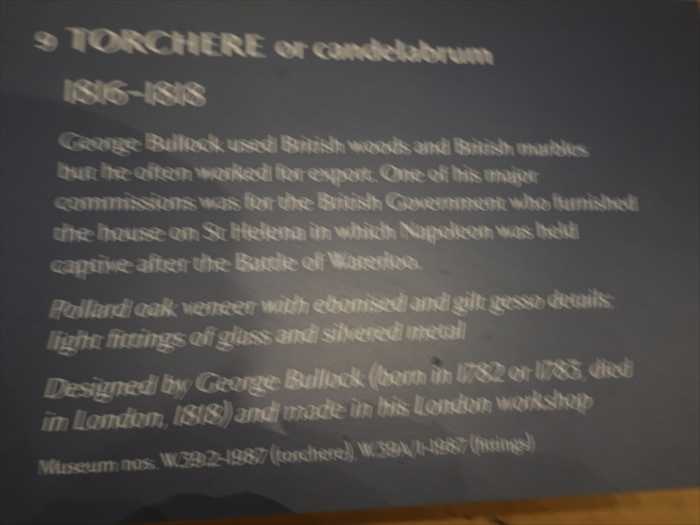

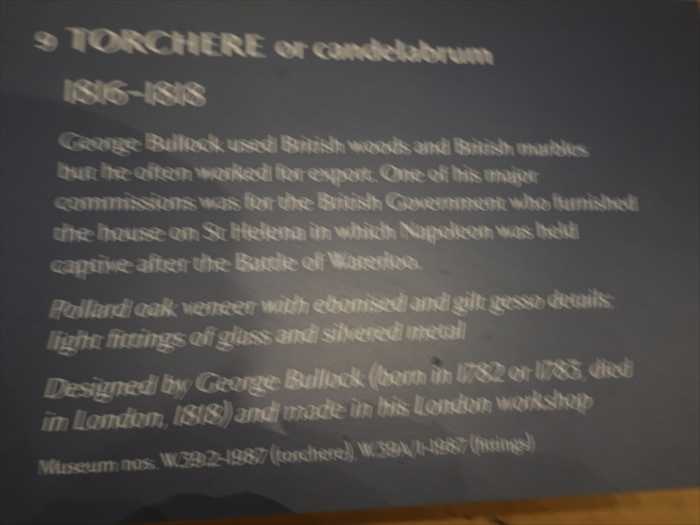

9 TORCHERE or candelabrum・ トーチャー(燭台)またはカンデラブラ

「 9 TORCHERE or candelabrum

【 9 トーチャー(燭台)またはカンデラブラ

V&A博物館(Victoria and Albert Museum, London)内の

「 CLORE STUDY AREA(クロア・スタディ・エリア)121室 」 の入口。

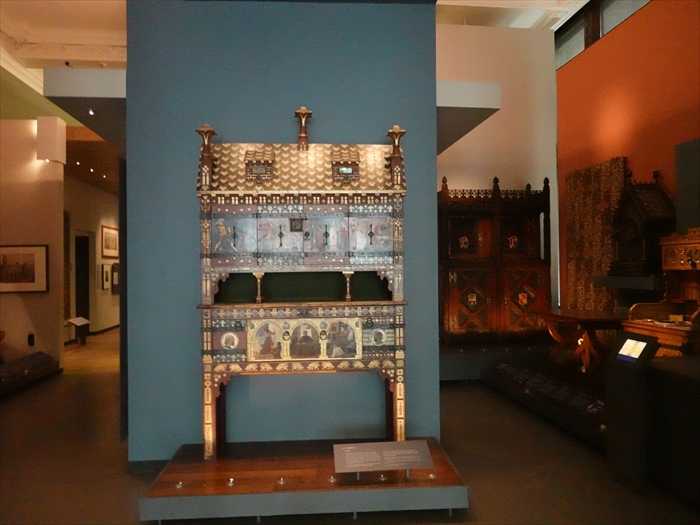

この展示はV&Aの Medieval & Renaissance Galleriesに置かれており、中世美術の実物に

囲まれながら「19世紀の中世趣味」を示す重要なコントラスト作品。

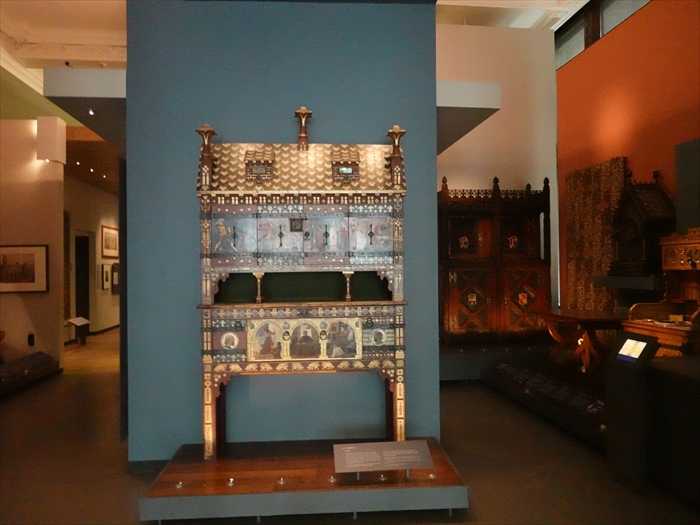

「 The Yatman Cabinet(ヤトマン・キャビネット) 」👈️リンク。

近づいて。

の一部。

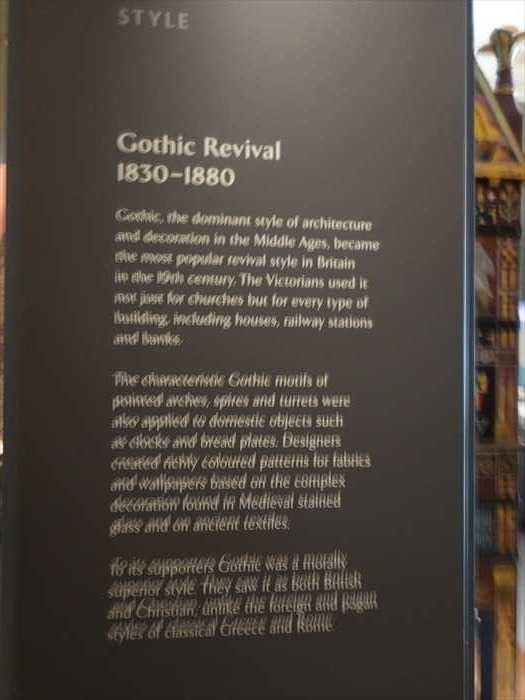

「Gothic Revival(ゴシック・リヴァイヴァル)」 の解説

「 STYLE

Christian, unlike the foreign and pagan styles of classical Greece and Rome.」

【 様式

支持者たちにとって、ゴシック様式は道徳的に優れた様式と見なされました。彼らはそれを

「外国的で異教的な古代ギリシャやローマの様式」とは異なり、「英国的かつキリスト教的」

なものと考えたのです。】

「 Gothic Revival(ゴシック・リヴァイヴァル) 」セクション に展示されている

教会祭具・聖具 の一式。

「 Religion in Britain 1800–1900

In 1800 the Church of England, the established church, exercised a unique power.

Methodists and other Protestants, Roman Catholics, members of other faiths and

atheists all faced obstacles to education, professional advancement and public office.

The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 is the best known of many changes in the law

that marked the development of religious freedom and led to the gradual removal of

bars to education or employment on religious grounds.Religion in 19th century Britain

was fiercely debated and different groups held stronglyopposing views. All religious

groups were active in building churches, chapels, meetinghouses or synagogues to

provide for the spiritual needs of existing communities and for those that were

developing in the expanding cities. Religion also became the spurto many programmes

of social care for the poor. Religious observance came to be seen as a mark of

respectability and individuals and communities spent large amounts on building and

decorating their places of worship.」

【 イギリスにおける宗教 1800–1900

すべての宗教団体は、既存の共同体や拡大しつつある都市の新しい共同体の精神的ニーズに

応えるため、教会・礼拝堂・集会所・シナゴーグの建設に力を注ぎました。また宗教は、

貧困層への多くの社会福祉プログラムの原動力にもなりました。宗教的な実践は

「社会的尊敬性の印」とみなされ、個人も共同体も礼拝所の建設や装飾に多額の資金を

投じるようになったのです。】

「 The Church 1840–1900

complete contents. As demand increased, specialist suppliers such as Cox & Sons

(established 1837) and Jones & Willis (established 1855) church furnishings could be

ordered from published catalogues.」

【 教会 1840–1900

設計しました。需要が高まるにつれて、Cox & Sons(1837年創業) や Jones & Willis

(1855年創業) などの専門業者が登場し、教会用の家具や調度品を出版されたカタログから

注文できるようになりました。】

・・・ もどる ・・・

・・・ つづく ・・・

部屋の全景をネットの写真から。

Design 1900–Nowギャラリーの長い通路・Room NO 76 .

V&A の National Art Library(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー) の書庫 が見える

一角二層吹き抜けに鋳鉄の手すり、壁一面の木製書架、天窓からの採光という内装が決め手。

手前にあるプロダクトの展示ケースは、ギャラリー側の通路に置かれており、ガラス越しに

実際のライブラリーの本棚が見える構成になっていた。

中の書籍は本物で、閲覧は登録制 (閲覧室は別室) とのこと。

・英国随一の装飾美術・デザイン専門図書館。展覧会図録、装飾美術・建築・ファッション・

・書庫はクローズドスタック(直接は取れず、請求して閲覧)。閲覧室の参考棚のみ開架。

利用の基本(実務メモ)

・無料で利用可。ただし資料の閲覧は利用者登録(身分証)が必要。

・事前にオンラインで請求→来館時に閲覧、の流れが標準。

・閲覧室では通常鉛筆のみ使用、飲食不可。資料撮影は可否が分かれるので

係員の指示に従う。

・ 落下防止バー: 各段の前面に通る金属バー。地震・人の動き・清掃時に閲覧ゾーン側への

落下防止&整列保持の役割。

必要に応じて上げ下げして本を出し入れしする と。

・下段のガラス扉 :大型判(フォリオサイズ)の画集・製図集・製本済み雑誌などを収納。

湿度や埃から守るためガラス扉付き と。

National Art Library(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー)書庫の外壁。

右手の背の高い木製書架は図書館の実物の書庫、左手の白い展示ケースと

“ Sustainability and Subversion ”のサインはデザイン・ギャラリーのテーマ展示の一部。

二層構成になっており、 上階は鋳鉄手すりの回廊、天井からシャンデリア

「Design 1900–Now」ギャラリー通路から見た、National Art Library

(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー)書庫の外壁。

右側:John Madejski Garden

左側:National Art Library(ナショナル・アート・ライブラリー)の入口

金文字「NATIONAL ART LIBRARY」扉はこの左壁沿い(写真フレーム外)にあった。

前方:西(Room 74 側)

Level2 のMAP。 ■ がRoom NO 76

そしてこれが金文字「 NATIONAL ART LIBRARY 」の入口。

近づいて。

Art Library(閲覧室)への入口。

Art Library(閲覧室)内部の写真 。

・まっすぐ先のガラスの両開き扉が、外の Design 1900–Now(Room 76)通路へ戻る出入口。

・右側のアーチ窓は 南側(外光が入る窓列)。

・左側の高い本棚の壁が 北面で、この壁の向こう側が先ほど歩かれた展示通路(Room 76)。

・机の並びや緑色シェードのスタンドは、閲覧室の標準レイアウト。

ズームして。

・机が整然と並び、緑のスタンドランプと胸像(バスト)が列状に配置されているのが

閲覧室の標準レイアウト。

閲覧室の標準レイアウト。

・画面一面に見える高い本棚の壁は、歩いた Design 1900–Now(Room 76)の通路と

背中合わせの“北面”。

背中合わせの“北面”。

・金文字「NATIONAL ART LIBRARY」の入口は、この本棚の並ぶ北面の中央付近

(写真の右奥方向にあたる位置)にあった。

扉を出ると、先ほどの展示通路(Room 76)に出た。

(写真の右奥方向にあたる位置)にあった。

扉を出ると、先ほどの展示通路(Room 76)に出た。

中庭南辺の通路(Room 76)から東寄り(No.25 付近)の階段/エレベーターで Level 3 へ 上がり 、Rooms 118–125 の表示に従って進む。

V&A の “BRITAIN (1760–1900)”(British Galleries) への案内サイン。

表示の 118–…(~125c など) は該当する部屋番号を示す。

産業革命期からヴィクトリア時代までの英国の家具・銀器・陶磁・室内装飾などを展示。

このケースは、V&Aの英国ギャラリーで紹介されている Vasemania(花瓶熱) を一望できる展示。

正面から。

18~19世紀の新古典主義期、古代ギリシャ・ローマの「壺(vase)」の形や装飾が大流行し、

実用品や室内装飾までをも壺風にしてしまった――という現象を、実物で示していたのだ。

・中央の大壺:

古代ギリシャのクラテル(混酒壺)型。黒地に赤い人物像の帯状画

(赤絵式”を思わせる意匠)で、18~19世紀の工房が古典壺を写したり

再解釈して作ったもの。

暖炉やコンソール上に飾る「ガーニチャー(壺飾りの組)」の主役であった。

(赤絵式”を思わせる意匠)で、18~19世紀の工房が古典壺を写したり

再解釈して作ったもの。

暖炉やコンソール上に飾る「ガーニチャー(壺飾りの組)」の主役であった。

・上段の小ぶりの壺群:

取っ手付きのアンフォラやオイノコエ型など、古典形のバリエーション。

素材は磁器・ストーンウェア・ガラスなどさまざま。

素材は磁器・ストーンウェア・ガラスなどさまざま。

・右下の金色の燭台:

よく見ると胴体が「壺の胴」形。花瓶のフォルムが燭台・茶筒・香水瓶

などの実用品にも転用されたことを示す好例です。

などの実用品にも転用されたことを示す好例です。

・左右に見える色ガラスの器:

多層ガラスを削って文様を出すカメオガラスや、色被せ

ガラスに金彩を施したものなど、壺モチーフがガラスにも波及

したことが分かります。

ガラスに金彩を施したものなど、壺モチーフがガラスにも波及

したことが分かります。

・背面の赤×金の額装パネル:

メダリオン(円形レリーフ)や古典主題の装飾で、壺と同じ

古代趣味を室内全体の意匠に広げた例。

・18世紀後半、ウェッジウッド(Josiah Wedgwood)が壺形の器を大量に生産し、彼自身が

この流行をvasemania(花瓶狂)と呼んだ。

古代趣味を室内全体の意匠に広げた例。

・18世紀後半、ウェッジウッド(Josiah Wedgwood)が壺形の器を大量に生産し、彼自身が

この流行をvasemania(花瓶狂)と呼んだ。

・ポンペイやヘルクラネウムの発掘、ギリシャ壺の版画集の出版(コレクターのハミルトン卿

など)がデザイン資料となり、陶磁器・金工・ガラス・家具の意匠にまで壺の語彙が

広がった。

など)がデザイン資料となり、陶磁器・金工・ガラス・家具の意匠にまで壺の語彙が

広がった。

「 Vasemania

Labels for the objects in this case are in a booklet to the right of the case.

Vases were a very important element of the Neo-classical style.The pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, who could hardly make them fast enough,

spoke of“vasemania”. They appeared as three-dimensional objects and as decorative

motifs. Vase forms also influenced the shape of practical items of all sorts, from tea

canistersto candlesticks. Designers plundered sources far and wide for new designs,

from Greekpottery to 16th- and 17th-century prints.」

【 ヴェーズマニア

このケース内の各作品ラベルは、ケース右手に置かれた冊子にあります。花瓶は新古典主義様式に

おいて非常に重要な要素でした。

陶磁器メーカーのジョサイア・ウェッジウッドは、需要に追いつけないほどで、この現象を

「ヴェーズマニア」と呼びました。花瓶は立体作品としてだけでなく、装飾モチーフ

としても登場しました。さらに花瓶の形は、茶葉用キャニスターから燭台に至るまで、実用品の

造形にも影響を与えました。デザイナーたちは新しい意匠を求め、ギリシャの陶器から

16~17世紀の版画にいたるまで、広範な資料を貪欲に参照しました。】

国王のゴールド・ステート・コーチの模型 。

・ロココ~新古典主義的な重厚な鍍金装飾に、四隅や側面にトリトンや海のモティーフが。

・実物のゴールド・ステート・コーチは戴冠式や大規模な儀礼で使われる王室馬車で、

ここでは展示用の縮尺模型として紹介されていた。

ここでは展示用の縮尺模型として紹介されていた。

・手前のパネルが下の説明板(オブジェクト番号 53)。

材質や設計者・装飾担当者の名がまとめられていた。

材質や設計者・装飾担当者の名がまとめられていた。

材質:

鍍金・彩色木、金属、絹、革、ビロード張り。

設計:

ウィリアム・チェンバース(1723–1796、スウェーデン生)

絵画:

G. B. チプリアーニ(1727–1785、イタリア)

彫刻:

ジョゼフ・ウィルトン(1722–1803、英国)

製作(車体):

サミュエル・バトラー(活動 1749–1798、英国)

発注:

王室(国王造営局)〔ジョージ三世の戴冠に関連して〕。

この模型は1760年ごろに作られた。

実物のゴールド・ステート・コーチは戴冠式や大規模な儀礼で使われる王室馬車 で、

ここでは展示用の縮尺模型として紹介されていた。

この模型は1760年ごろに作られた。

実物のゴールド・ステート・コーチは戴冠式や大規模な儀礼で使われる王室馬車 で、

ここでは展示用の縮尺模型として紹介されていた。

「 53 MODEL OF THE STATE COACH

About 1760

The basic design of this State Coach was intended to reflect Britain’s [power] underthe

new King George III. In the decoration by William Chambers, [painted] panels by

Giovanni Cipriani and carving by Joseph Wilton show [sea-gods] and figures of[Tritons] symbolising sea-power. The coach has been used since 1762 and is still used on

important ceremonial occasions.

new King George III. In the decoration by William Chambers, [painted] panels by

Giovanni Cipriani and carving by Joseph Wilton show [sea-gods] and figures of[Tritons] symbolising sea-power. The coach has been used since 1762 and is still used on

important ceremonial occasions.

Gilded and painted wood, metal, silk, leather and velvet upholstery

Designed by William Chambers (born in Gothenburg, Sweden, 1723–1796); painted by

Giovanni Battista Cipriani (Italian, 1727–1785); carving by Joseph Wilton(British,

1722–1803); coach built by Samuel Butler (British, active 1749–1798).

Commissioned for the Office of the [King’s/Works] for the [Coronation] of George III;

completed in 1762. This model was made c.1760.

Giovanni Battista Cipriani (Italian, 1727–1785); carving by Joseph Wilton(British,

1722–1803); coach built by Samuel Butler (British, active 1749–1798).

Commissioned for the Office of the [King’s/Works] for the [Coronation] of George III;

completed in 1762. This model was made c.1760.

Museum no. [----]」

【 53 国王のゴールド・ステート・コーチの模型

1760年ごろ

このステート・コーチ(王室儀礼用の馬車)の基本設計は、新王ジョージ三世のもとでのイギリスの(海上)パワーを表す意図で作られました。建築家ウィリアム・チェンバースの

デザインにより、ジョヴァンニ・バッティスタ・チプリアーニの絵画パネルと、ジョゼフ・

ウィルトンの彫刻が施され、トリトン(海神)などの像が海軍力を象徴しています。

実物のコーチは1762年に完成し、以後も重要な国家儀礼で用いられてきました。】

「Britain (1760–1900)」セクションに展示されている部屋の装飾の一部。壁面と扉を含む

豪華なインテリアで、19世紀の英国室内装飾様式を示していた。

・扉

緑色の地に金の装飾枠をあしらった両開きのドア。枠には古典的なアカンサス文様や

幾何学的パターンが施され、華やかな仕上がり。

幾何学的パターンが施され、華やかな仕上がり。

・壁面パネル

深紅の地に、金の植物文様・幾何装飾が浮き上がるデザイン。ネオクラシカルな

「シンメトリー」と「規則性」が強調されており、18世紀末から19世紀初頭に流行した様式。

「シンメトリー」と「規則性」が強調されており、18世紀末から19世紀初頭に流行した様式。

・円形メダリオン画

扉の上には円形画(メダリオン)が額装されており、古典風の人物群像が描かれている。

これは神話や寓意画を題材にしている可能性が高く、部屋全体のテーマ性を示す装飾の一部。

これは神話や寓意画を題材にしている可能性が高く、部屋全体のテーマ性を示す装飾の一部。

・装飾要素

周囲には丸いロゼット(花飾り)、蔓草文様、金の縁取りが連続しており、ルネサンス風・

古代ローマ風のモチーフを取り入れている。

古代ローマ風のモチーフを取り入れている。

「 32 PART OF THE GLASS DRAWING ROOM, NORTHUMBERLAND HOUSE, LONDON

Designed from 1770; made 1773–1775

This panelling was from the glittering drawing room, panelled entirely in glass, that the

architect Robert Adam designed for the 1st Duke and Duchess of Northumberland at

their London house in the Strand. The scheme was based on the richly ornamentedi

nteriors of ancient and modern Rome. Adam used glass backed with coloured pigments

and metal foils to imitate the porphyry of Roman decoration and copied plaster and

painted decoration in gilded metal, cast from moulds.

architect Robert Adam designed for the 1st Duke and Duchess of Northumberland at

their London house in the Strand. The scheme was based on the richly ornamentedi

nteriors of ancient and modern Rome. Adam used glass backed with coloured pigments

and metal foils to imitate the porphyry of Roman decoration and copied plaster and

painted decoration in gilded metal, cast from moulds.

Given by Dr. R. A. McIntosh FSA

Museum No. W.12-1972」【 32 ガラス張り応接室の一部 ノーサンバーランド・ハウス(ロンドン)

1770年に設計、1773~1775年制作

このパネル装飾は、ロンドンのストランド通りにあったノーサンバーランド公爵・公爵夫人邸の、

きらびやかな「ガラス張り応接室」から移されたものです。建築家ロバート・アダムが

設計しました。

きらびやかな「ガラス張り応接室」から移されたものです。建築家ロバート・アダムが

設計しました。

デザインの構想は、古代ローマと近代ローマの華麗な装飾的室内に基づいています。

アダムは、ガラスの裏に着色顔料や金属箔を貼り、ローマ装飾に見られる斑岩(ポルフィリー)を

模倣しました。また、石膏細工や彩色装飾を、鋳型で鋳造した金メッキ金属で再現しました。

アダムは、ガラスの裏に着色顔料や金属箔を貼り、ローマ装飾に見られる斑岩(ポルフィリー)を

模倣しました。また、石膏細工や彩色装飾を、鋳型で鋳造した金メッキ金属で再現しました。

寄贈者:R.A. マッキントッシュ博士(FSA会員)

収蔵番号:W.12-1972】

ピア・グラスに取り付けられた祭壇額。

・「ピア・グラス(pier glass)」とは、壁と壁の間(柱=pier の間)に置かれる大型の姿見鏡 を

意味します。しばしば家具調の装飾が施され、室内を豪華に見せる効果がありました。

・この鏡は、先ほどの案内板にあった「ノーサンバーランド・ハウスのガラス張り応接室」の

一連の装飾の一部であり、部屋の豪華さを象徴する重要な要素 と。

・フレームの左右に配置された人物像(天使や寓意像)は、当時流行したネオクラシカル装飾の

典型で、金箔仕上げによって室内照明の輝きをさらに増す役割を果たしました。

「 38 MIRROR

Mounted in a pier glass

1770–1771

This pier glass was made in Rome between 1770 and 1771 for Robert Adam, one of

the most fashionable architects in England. It was designed for the glass drawing

room at Northumberland House, London. The richly carved and gilded frame was

made by Seffer in Alken, one of the best carvers in London in the 18th century.

Carved and gilded wood frame」 the most fashionable architects in England. It was designed for the glass drawing

room at Northumberland House, London. The richly carved and gilded frame was

made by Seffer in Alken, one of the best carvers in London in the 18th century.

【 38 ピア・グラスに取り付けられた祭壇額

1770–1771年

このピア・グラス(大きな姿見鏡)は、1770年から1771年の間にローマで制作され、当時イギリスで最も人気のあった建築家の一人、ロバート・アダムのために作られました。

ロンドンのノーサンバーランド・ハウスにある「ガラス張り応接室(Glass Drawing Room)」

用に設計されたものです。】

イギリス・ギャラリー(1760–1900) の展示風景で、18世紀末から19世紀にかけての

「 ファッショナブルな暮らし(Fashionable Living) 」をテーマにした一角。

・中央の肖像画

中年の男性像で、イギリスの富裕層あるいは文化人を描いた肖像画。家具とともに展示され、

邸宅の室内装飾を再現。

邸宅の室内装飾を再現。

・左右の小型楕円画(オーバル絵画)

神話または寓意的な場面を描いた小型絵画。肖像と組み合わせて飾られており、当時の邸宅の

壁面装飾の一例を示している。

壁面装飾の一例を示している。

・家具類

中央の金彩のコンソール・テーブル:ロココから新古典主義へ移行期に流行した、壁際に置く

装飾的な半卓。

装飾的な半卓。

緑張りの椅子、透かし細工の背もたれ椅子など、デザインの異なる椅子が並べられ、

18世紀後半~19世紀前半の室内様式を比較できるようになっている。

18世紀後半~19世紀前半の室内様式を比較できるようになっている。

・左端の展示物

ガラスケース内にシャンデリア付きの楕円鏡(Irish Mirror with Chandelier, 1780–1790)

が見えており、アイルランドのカットグラス産業の発展を示す展示が隣接している。

が見えており、アイルランドのカットグラス産業の発展を示す展示が隣接している。

44 IRISH MIRROR WITH CHANDELIER・アイルランド製 鏡付きシャンデリア

1780–1790。

・楕円形の鏡の前に、 カット・グラスで作られたシャンデリア

が取り付けられています。

・鏡がシャンデリアの光と煌めきを反射し、室内をより豪華に演出する仕組み。

・細かくカットされたガラスのプリズムやドロップ(涙型パーツ)が光を乱反射させ、

ダイヤモンドのような輝きを放ちます。

ダイヤモンドのような輝きを放ちます。

・この構造は、 18世紀末のアイルランドで発展したガラス工芸の特色

をよく表している。

「 44 IRISH MIRROR WITH CHANDELIER

1780–1790

In the last twenty years of the 18th century Ireland developed a thriving glass industry,

which supplied its own markets as well as those of Britain. Mirrors set with a cut-glass

chandelier were an Irish speciality. The Neo-classical style, with its emphasis on glitter

and small-scale detail, was particularly suited to the decoration of cut-glass for lighting.

which supplied its own markets as well as those of Britain. Mirrors set with a cut-glass

chandelier were an Irish speciality. The Neo-classical style, with its emphasis on glitter

and small-scale detail, was particularly suited to the decoration of cut-glass for lighting.

Cut glass

Made in Ireland, possibly in Dublin

Museum no. C.6-1974」 【 44 シャンデリア付きアイルランド製鏡

1780–1790年

18世紀後半の20年間、アイルランドは活発なガラス産業を発展させ、自国市場だけでなく

英国市場にも供給していました。カット・グラス製のシャンデリアを組み込んだ鏡は、

アイルランド特有の製品でした。

英国市場にも供給していました。カット・グラス製のシャンデリアを組み込んだ鏡は、

アイルランド特有の製品でした。

きらめきと精緻な細部を強調する新古典主義様式は、照明用のカット・グラス装飾に特に

適していました。

適していました。

素材:カット・グラス

制作地:アイルランド(おそらくダブリン)】

V&A(ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館)「 THE WOLFSON GALLERIES(118) 」 の入口部分。

・The Wolfson Galleries(ウルフソン・ギャラリー) は、V&Aの中で18世紀から19世紀に

かけてのイギリス美術・工芸を集中的に展示しているエリア。

かけてのイギリス美術・工芸を集中的に展示しているエリア。

・ギャラリー番号 118 は、その中でも「産業革命期の工芸」「新素材・新技術」

「ファッショナブルな暮らし」といったテーマを取り扱う区画の一つです。

「ファッショナブルな暮らし」といったテーマを取り扱う区画の一つです。

・入り口横のパネルには「Developments in the Metal Trades 1740–1840(1740〜1840年の

金属産業の発展)」などの展示解説が掲示されており、産業革命期の英国を象徴する工芸品

(シェフィールド・プレート、カット・スティール、ブリタニア・メタルなど)が

紹介されていた。

金属産業の発展)」などの展示解説が掲示されており、産業革命期の英国を象徴する工芸品

(シェフィールド・プレート、カット・スティール、ブリタニア・メタルなど)が

紹介されていた。

「 WHAT WAS NEW?

Developments in the Metal Trades 1740–1840

Between 1740 and 1840 the metal trades expanded dramatically. New materials were energetically exploited and new techniques of manufacture and marketing were applied.

These advances resulted in a wide range of cheaper goods. The search for cheap

substitutes for silver led to the invention of Sheffield plate, made from copper with a

fine layer of silver. Alloys such as Britannia metal and Pakfong, a golden-coloured metal

from China, were also used. Japanning imitated lacquer with paint. Brittly goodsand

jewellery were decorated with cut steel that sparkled like diamonds.

The use of labour-saving machinery meant that goods could easily be made insubstitutes for silver led to the invention of Sheffield plate, made from copper with a

fine layer of silver. Alloys such as Britannia metal and Pakfong, a golden-coloured metal

from China, were also used. Japanning imitated lacquer with paint. Brittly goodsand

jewellery were decorated with cut steel that sparkled like diamonds.

standard forms. These goods could then be exported and sold throughout the world.」

【 新しいものは何か?

金属産業の発展 1740–1840

1740年から1840年の間、金属産業は飛躍的に拡大しました。新しい素材が積極的に利用され、

製造や販売の新しい技術が導入されました。

製造や販売の新しい技術が導入されました。

これらの進歩により、安価な製品が幅広く生産されるようになりました。銀の代用品を求めた

結果、シェフィールド・プレートが発明されました。これは銅に薄い銀の層をかぶせた

ものでした。

結果、シェフィールド・プレートが発明されました。これは銅に薄い銀の層をかぶせた

ものでした。

また、ブリタニア・メタルや、中国から伝わった金色合金の「パクフォン」も使用されました。

さらに「ジャパニング(Japanning)」と呼ばれる漆の模倣技法が塗料で施され、鋼を細かく

カットした装飾は宝石のように輝き、装飾品やジュエリーを飾りました。

労力を節約する機械の利用によって、製品は標準化された形で容易に大量生産されるさらに「ジャパニング(Japanning)」と呼ばれる漆の模倣技法が塗料で施され、鋼を細かく

カットした装飾は宝石のように輝き、装飾品やジュエリーを飾りました。

ようになり、輸出され、世界中で販売されました。】

作品名:The Campbell Sisters dancing a Waltz

ワルツを踊るキャンベル姉妹 作家:Lorenzo Bartolini(1777–1850、イタリア) 。

・特徴

・二人の若い女性・ キャンベル姉妹 Emma & Julia の二人

が寄り添って歩く姿。

・衣の表現は古代風のトーガ風で、流れるような薄布の表現はカノーヴァ派の特徴。

・台座には花綱(ガーランド)が飾られ、祝祭的な雰囲気を添えている。

・テーマ

・寓意像(友情 Friendship / 調和 Harmony / 優雅 Grace など)

・あるいは神話の二人の女性人物(ニンフや女神のペア)。

・新古典主義では、神話的題材を「理想化された女性像のペア」として表現することが多く、

この作品もその系統。

この作品もその系統。

「 FASHIONABLE LIVING

The Private Sculpture Gallery

Many British collectors developed a taste for classical sculpture during the Grand Tour

of the mid-18th through Europe as young men. On their return, the owners created

specially designed settings for the sculptures they had bought, either in their London

or their country houses.

of the mid-18th through Europe as young men. On their return, the owners created

specially designed settings for the sculptures they had bought, either in their London

or their country houses.

Such interiors could often be seen at Holkham Hall in Norfolk, where the Sculpture

Gallery was established in the 1750s. At Syon House, Robert Adam designed a

sculpture gallery during the 1760s.

In the early 19th century, a new interest in contemporary sculpture, in the classicalGallery was established in the 1750s. At Syon House, Robert Adam designed a

sculpture gallery during the 1760s.

style, developed, aimed at the decoration of fashionable domestic interiors.

In Britain, the leading sculptor was Antonio Canova’s pupil, Antonio d’Este,

who produced idealised marble sculptures of mythological subjects.」

【 ファッショナブルな暮らし

個人彫刻ギャラリー

18世紀中頃、多くのイギリス人コレクターは「グランド・ツアー」(ヨーロッパ大陸への

教養旅行)を通じて古典彫刻への嗜好を育みました。若者として大陸で学び、収集した彫刻を

持ち帰ると、彼らはそれを展示するための特別な空間を、自宅のロンドン邸宅や地方の館に

設けました。

教養旅行)を通じて古典彫刻への嗜好を育みました。若者として大陸で学び、収集した彫刻を

持ち帰ると、彼らはそれを展示するための特別な空間を、自宅のロンドン邸宅や地方の館に

設けました。

そのような室内装飾は、ノーフォークのホルカム・ホール(Holkham Hall、1750年代に

彫刻ギャラリーを設置)や、ロバート・アダムが1760年代に設計したサイオン・ハウス

(Syon House)の彫刻ギャラリーで見ることができます。

彫刻ギャラリーを設置)や、ロバート・アダムが1760年代に設計したサイオン・ハウス

(Syon House)の彫刻ギャラリーで見ることができます。

19世紀初頭には、新古典主義様式の現代彫刻への関心が高まり、流行の邸宅インテリア装飾に

用いられるようになりました。イギリスにおける代表的な彫刻家は、アントニオ・カノーヴァの

弟子アントニオ・デステ(Antonio d’Este)であり、彼は神話的主題を理想化した大理石像を

制作しました。】

用いられるようになりました。イギリスにおける代表的な彫刻家は、アントニオ・カノーヴァの

弟子アントニオ・デステ(Antonio d’Este)であり、彼は神話的主題を理想化した大理石像を

制作しました。】

V&A(ヴィクトリア&アルバート博物館)の ブリティッシュ・ギャラリー の一室。

・中央手前

黒い台座の上に大きな 犬の彫像(セント・バーナード犬のような姿) が置かれています。

白と黒のコントラストがあり、毛並みを強調した写実的な作品。

白と黒のコントラストがあり、毛並みを強調した写実的な作品。

・中央奥

大きなシャンデリアが天井から吊るされ、空間に豪華な雰囲気を与えている。

・右手の壁面(黄色)

18世紀後半から19世紀の英国家具・調度品が並んでいる。金装飾の椅子やソファ、

楕円形の額鏡(オーバル・ミラー)、さらに壁面には肖像画や小型絵画が掛けられている。

楕円形の額鏡(オーバル・ミラー)、さらに壁面には肖像画や小型絵画が掛けられている。

・左手の壁面(紫〜黒)

絵画や漆工芸品(日本や中国からの輸入品も含まれる)が飾られており、英国の室内装飾が

「東洋趣味(シノワズリー)」を取り込んでいた様子を反映している。

「東洋趣味(シノワズリー)」を取り込んでいた様子を反映している。

British Galleries 1500–1900 の「19世紀室内装飾」展示 の一部。

・このセクションは、19世紀イギリス上流階級の邸宅サロンを再現する構成。

・家具・肖像画・鏡・室内装飾を一体的に展示し、当時の「ファッショナブルな暮らし

(Fashionable Living)」の様子を伝えています。

・背景壁の黄色は、当時流行した室内色彩を意識した演出でもある。

中央

・楕円形の大きな鏡(オーバル・ミラー)

・豪華な金色の額縁に収められ、上部には羽根飾りのようなクラウン装飾。

・19世紀初頭、リージェンシー様式やロココ復興の影響を示す華麗な意匠。

左側

・赤い張り地の寝椅子(カウチ/シェーズロング)

・金のフレームに赤い織物張り。

・社交空間やサロンで使われた家具。

・大型の肖像画(女性像)

・豪華な金のフレームに収められた油彩画。

・この展示セクションでは、肖像画と家具を組み合わせて「邸宅のインテリア空間」を

再現しています。

再現しています。

右側

・緑の張り地の肘掛椅子

・ギリシャ風の脚部装飾があり、ネオクラシカル(新古典主義)の影響を示す。

・小型の黒いスタンド(読書台または譜面台のような家具

・二枚の肖像画

・左:白いドレスを着た女性像。

・右:黒衣をまとった男性像。

Spode(スポード窯)のディナーサービス (約1820年)。

上段

・小型丸皿 ×6

・長方形小皿 ×1

・中皿(楕円・八角形)×2

中段

・楕円大皿(ミートディッシュ)×2

・中型楕円皿(野菜皿またはサイドディッシュ)×2

・丸皿(スープ皿・デザート皿)×2

下段(左右の棚も含む)

・深鉢(サラダボウル、野菜ボウル)×2

・オーバル大鉢 ×1

・蓋付きスープチュリーン ×2

・ソースボート(片口小鉢)×1

最下段

・大型のサーヴィングプレート(中央に大花束文)×1

「 PART OF A DINNER SERVICE

About 1820; numbers 30–34, 1831

This large service is characteristic of the extensive and richly decorated porcelain

that was available to an increasingly wide range of buyers during this period.

Marketing through London showrooms played an important role in the selling of

such ensembles. Massed displays were a familiar sight to the visiting public as in the

Wedgwood showroom illustrated on the left.

that was available to an increasingly wide range of buyers during this period.

Marketing through London showrooms played an important role in the selling of

such ensembles. Massed displays were a familiar sight to the visiting public as in the

Wedgwood showroom illustrated on the left.

Porcelain

【 ディナーサービスの一部

約1820年(カタログ番号30–34, 1831年)

この大規模なディナーサービスは、19世紀初頭に広く出回った、装飾豊かで華やかな磁器を

代表しています。当時、ロンドンのショールームでの販売戦略が重要な役割を果たしました。

ウェッジウッドのショールーム展示に見られるように、大規模なディスプレイは訪問客に

とっておなじみの光景でした。

代表しています。当時、ロンドンのショールームでの販売戦略が重要な役割を果たしました。

ウェッジウッドのショールーム展示に見られるように、大規模なディスプレイは訪問客に

とっておなじみの光景でした。

素材:磁器

製造:スポード窯(Spode Factory)、ストーク=オン=トレント(Staffordshire州)】

「The Wolfson Galleries(ウォルフソン・ギャラリー)」の一部で、18世紀末〜19世紀

初頭の室内装飾と家具 を再現するようなセクション。

写真中央には 大きな円形の凸面鏡(Convex Mirror, 約1790年) が掲げられています。

鏡は金箔仕上げの松材フレームに収められ、上下にアカンサスの葉飾りや鷲のモチーフが

加えられている。これは当時の流行で、家具デザイン集(George Smith, 1808年刊)でも

紹介された様式。

1.凸面鏡(Convex Mirror, c.1790)

・松材、金箔仕上げ、凸面ガラス。

・装飾には鷲(eagle)、アカンサスの葉が使われ、クラシカルな権威を象徴。

・所蔵番号:W.25-1922。

2.肖像画(右壁)

・女性の肖像(白いドレス、赤い背景)。

・男性の肖像(軍服を思わせる装い)。

→ いずれも19世紀初頭の貴族・上流階級を描いた作品。鏡と共に飾られることで、

当時の邸宅の「ファッション性」を表現。

当時の邸宅の「ファッション性」を表現。

3.家具(下部)

・赤い張地の寝椅子(シェーズ・ロング)。

・緑の布座面の椅子(ギリシャ風装飾)。

・小型テーブル(木製、彫刻装飾)。

→ ナポレオン時代からジョージアン期にかけての「新古典主義スタイル」を示す。

「 19 CONVEX MIRROR

About 1790

Mirror of this type became popular in about 1790. Various examples were illustrated

in George Smith's Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, published in 1808. This example shows how various details such as the eagle and the

acanthus leaf were added to a basic circular mirror.

in George Smith's Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, published in 1808. This example shows how various details such as the eagle and the

acanthus leaf were added to a basic circular mirror.

Pinewood, gilded with convex glass

Museum no. W.25-1922」 【 19 凸面鏡

約1790年

この種の鏡は 1790年頃 に流行しました。さまざまな例が、1808年に出版されたジョージ・

スミスの 『家庭用家具と室内装飾のデザイン集』 に図示されています。本作は、基本的な

円形の鏡に、鷲(イーグル) や アカンサスの葉 などの細部装飾が加えられた様子を

示しています。

スミスの 『家庭用家具と室内装飾のデザイン集』 に図示されています。本作は、基本的な

円形の鏡に、鷲(イーグル) や アカンサスの葉 などの細部装飾が加えられた様子を

示しています。

素材: 松材、金箔仕上げ、凸面ガラス

所蔵番号: W.25-1922】

左側の肖像画

・タイトル: Mary Linwood

・画家: ジョン・ホップナー(John Hoppner, RA, 1758–1810)

・制作時期: 約1800年

・技法: 油彩・カンヴァス

この肖像画は、羊毛刺繍による巨匠絵画の模写作品で知られた

メアリー・リンウッド (1756–1845) を描いた もの。

メアリー・リンウッド (1756–1845) を描いた もの。

彼女はレスター・スクエア(ロンドン)でギャラリーを運営し、刺繍芸術を

「高級芸術の展示形式」と結びつける先駆者であった。

「高級芸術の展示形式」と結びつける先駆者であった。

ジョン・ホップナーは当時のイギリスを代表する肖像画家の一人で、リンウッドを優雅な白い

ドレス姿で描き、彼女の文化的な地位と知的活動を示している。

右側の肖像画 。

・油彩画ではなく、メアリー・リンウッド(Mary Linwood)による毛糸刺繍の

ナポレオン・ボナパルト像(19世紀初頭のイギリス肖像画) であろう。

ドレス姿で描き、彼女の文化的な地位と知的活動を示している。

右側の肖像画 。

・油彩画ではなく、メアリー・リンウッド(Mary Linwood)による毛糸刺繍の

ナポレオン・ボナパルト像(19世紀初頭のイギリス肖像画) であろう。

・作品:Portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte(刺繍)

・作者:Mary Linwood(1756–1845)

・年代:18世紀末〜19世紀初頭

・技法:クルーエル刺繍(coloured worsteds)

・サイズ:およそ 2 ft 7 in × 2 ft 2 in(資料記載)

・所蔵:Victoria and Albert Museum(収蔵番号 1438-1874)

「 13 MARY LINWOOD

About 1800

Mary Linwood (1756–1845) was famous for exhibiting her crewel wool needlework

copies of old master paintings in her gallery in Leicester Square, London. Linwood's

enterprise was an example of how the luxury goods trades began to use similar

techniques of display to those used for high art, attracting customers with public

exhibitions.

copies of old master paintings in her gallery in Leicester Square, London. Linwood's

enterprise was an example of how the luxury goods trades began to use similar

techniques of display to those used for high art, attracting customers with public

exhibitions.

Oil on canvas

By John Hoppner RA (born in 1758, died in 1810)

Bequeathed by Miss Ellen Markland

Museum no. 1439-1874」 【 13 メアリー・リンウッド

1800年頃

メアリー・リンウッド(1756–1845)は、ロンドンのレスター・スクエアにある自身の

ギャラリーで、オールド・マスター(巨匠画家)の作品を羊毛刺繍(クルーエル刺繍)で

再現した作品を展示したことで有名でした。

ギャラリーで、オールド・マスター(巨匠画家)の作品を羊毛刺繍(クルーエル刺繍)で

再現した作品を展示したことで有名でした。

リンウッドの事業は、高級品の取引が「美術作品の展示」で用いられるのと同じような

展示手法を取り入れ、公開展示によって顧客を惹きつけるようになった一例です。

展示手法を取り入れ、公開展示によって顧客を惹きつけるようになった一例です。

油彩・カンヴァス

画家:ジョン・ホップナー RA(1758年生 – 1810年没)

エレン・マークランド嬢の遺贈

美術館番号:1439-1874】

「TEAPOY

The teapoy became popular in about 1800 as a table with receptacles for tea.

This example is close to the design included in Peter and Michael Angelo Nicholson’s

Practical Cabinet-maker, published in 1826. A copy is displayed nearby. Such pattern

books not only provided designs for cabinet-makers but also influenced popular taste.

Carved mahogany

By an unknown British maker

Purchased with the assistance of the Brigadier Clark Fund

Museum no. W.16-1973」

【 15 ティーポイ(茶卓)

1825–1830年

ティーポイは、1800年頃にお茶用の容器を収める小卓として人気を博しました。

この作品は、ピーターとマイケル・アンジェロ・ニコルソンの著書『実用家具製作者 (Practical

Cabinet-maker)』(1826年刊行)に掲載されたデザインに近いものです。その本の一部が

近くに展示されています。このような「パターン・ブック」は、家具職人にデザインを

提供しただけでなく、大衆の嗜好にも影響を与えました。

この作品は、ピーターとマイケル・アンジェロ・ニコルソンの著書『実用家具製作者 (Practical

Cabinet-maker)』(1826年刊行)に掲載されたデザインに近いものです。その本の一部が

近くに展示されています。このような「パターン・ブック」は、家具職人にデザインを

提供しただけでなく、大衆の嗜好にも影響を与えました。

素材:マホガニー材の彫刻

作者:不詳(イギリスの製作者)

ブリガディア・クラーク基金の援助により購入

所蔵番号:W.16-1973】

レディ・アン・ハミルトン ・ Lady Anne Hamilton (1766–1846) 👈️リンク。

・レディ・アン・ハミルトン は、王族に仕えた著名な宮廷女性で、特に キャロライン王妃

(ジョージ4世妃)の侍女・側近 として知られています。

(ジョージ4世妃)の侍女・側近 として知られています。

・彼女は王妃キャロラインがロンドンに帰国した際の「議会審問(離婚裁判のような性質)」に

同席し、その忠誠心から政治的にも注目されました。

同席し、その忠誠心から政治的にも注目されました。

・絵画では、黒いドレスと大きな帽子(当時の宮廷・社交界での正装) を身につけ、威厳のある

姿で表されています。背後の赤いカーテンや椅子にかけられた毛皮付きマント

(アーミン=白テンの毛皮)は、貴族的な地位や儀礼を象徴している。

姿で表されています。背後の赤いカーテンや椅子にかけられた毛皮付きマント

(アーミン=白テンの毛皮)は、貴族的な地位や儀礼を象徴している。

9 TORCHERE or candelabrum・ トーチャー(燭台)またはカンデラブラ

「 9 TORCHERE or candelabrum

1816–1818

George Bullock used British woods and British marbles, but he often worked for export.

One of his major commissions was for the British Government who furnished the house

on St Helena in which Napoleon was held captive after the Battle of Waterloo.

One of his major commissions was for the British Government who furnished the house

on St Helena in which Napoleon was held captive after the Battle of Waterloo.

Pollard oak veneer with ebonised and gilt gesso details; light fittings of glass and

silvered metal

silvered metal

Designed by George Bullock (born in 1782 or 1783, died in London, 1818) and

made in his London workshop

Museum nos. W.62A-1887 (torchere), W.62B-1887 (sconce)」made in his London workshop

【 9 トーチャー(燭台)またはカンデラブラ

1816–1818年

ジョージ・ブロックはイギリス産の木材や大理石を用いたが、しばしば輸出向けの仕事も行った。

彼の主要な仕事のひとつは、ワーテルローの戦い後にナポレオンが幽閉されたセント・ヘレナ

島の邸宅を、イギリス政府の依頼で家具調度したことである。

彼の主要な仕事のひとつは、ワーテルローの戦い後にナポレオンが幽閉されたセント・ヘレナ

島の邸宅を、イギリス政府の依頼で家具調度したことである。

素材:斑木(ポラード・オーク)の化粧張り、黒色仕上げと金色ジェッソ装飾、ガラスおよび

銀メッキ金属の照明器具

銀メッキ金属の照明器具

デザイン:ジョージ・ブロック(1782年または1783年生、1818年ロンドン没)

製作:彼のロンドン工房

所蔵番号:W.62A-1887(燭台)、W.62B-1887(ブラケット燭台)】

V&A博物館(Victoria and Albert Museum, London)内の

「 CLORE STUDY AREA(クロア・スタディ・エリア)121室 」 の入口。

この展示はV&Aの Medieval & Renaissance Galleriesに置かれており、中世美術の実物に

囲まれながら「19世紀の中世趣味」を示す重要なコントラスト作品。

「 The Yatman Cabinet(ヤトマン・キャビネット) 」👈️リンク。

・このキャビネットは、Charles Francis B. Yatman(1823–1902) の依頼で作られた

豪奢な家具で、彼の名前から「Yatman Cabinet」と呼ばれています。

豪奢な家具で、彼の名前から「Yatman Cabinet」と呼ばれています。

・外観はあたかも中世の聖遺物箱(Reliquary Shrine)のようにデザインされ、宗教画風の

パネル装飾やアーチ構造が特徴。

パネル装飾やアーチ構造が特徴。

・実際には19世紀の「ネオ・ゴシック様式(Gothic Revival)」の産物で、当時のイギリスで

流行した「中世趣味」を反映している。

流行した「中世趣味」を反映している。

近づいて。

キャビネットの扉や引き出しには、寓意的なパネル画がはめ込まれており、

テーマは 「知識と文明の発展」 。

テーマは 「知識と文明の発展」 。

・左の場面:古代における知識の口伝・写本伝達

・中央の場面:学者(もしくは詩人・哲学者)が机に向かって記録

・右の場面:印刷機による本の大量生産(グーテンベルクの活版印刷を象徴)

つまり、知の継承 → 記録 → 普及 という人類文化の進展を順に表したもの。

の一部。

1.左側の大きな展示布

・中世の文様を模した複雑なパターンの織物または壁紙。

・「ゴシック・リヴァイヴァル」期のデザイナーたちが、ステンドグラスや古代織物に

基づいて色彩豊かなパターンを創作したことを示す典型例。

基づいて色彩豊かなパターンを創作したことを示す典型例。

2.中央〜右側の壁面

・壁掛け時計(木製ケース入り):19世紀らしい直線的で重厚なデザイン。

・文様図版(3点):ゴシック様式のパターンやアーチ形の装飾デザイン。

建築や家具、織物デザインに用いられたサンプル。

建築や家具、織物デザインに用いられたサンプル。

・建築画(右端額装):ゴシック風建築の立面図。19世紀に流行した教会・公共建築の

設計案を反映している可能性が高い。

設計案を反映している可能性が高い。

3.下部の椅子群

・赤い張地に金糸刺繍で「王冠」や「紋章」をあしらった椅子。

・おそらく 英国議会のチェア またはそれを模したデザイン。ネオ・ゴシック様式の家具として

権威や伝統を示す役割を持つ。

権威や伝統を示す役割を持つ。

「Gothic Revival(ゴシック・リヴァイヴァル)」 の解説

「 STYLE

Gothic Revival

1830–1880

1830–1880

Gothic, the dominant style of architecture and decoration in the Middle Ages, became

the most popular revival style in Britain in the 19th century. The Victorians used it not

just for churches but for every type of building, including houses, railway stationsand

banks.

the most popular revival style in Britain in the 19th century. The Victorians used it not

just for churches but for every type of building, including houses, railway stationsand

banks.

The characteristic Gothic motifs of pointed arches, spires and turrets were also applied

to domestic objects such as clocks and jewel plates. Designers created richly coloured

patterns for fabrics and wallpapers based on the complex decoration found in

Medieval stained glass and on ancient textiles.

To its supporters Gothic was a morally superior style. They saw it as both British andto domestic objects such as clocks and jewel plates. Designers created richly coloured

patterns for fabrics and wallpapers based on the complex decoration found in

Medieval stained glass and on ancient textiles.

Christian, unlike the foreign and pagan styles of classical Greece and Rome.」

【 様式

ゴシック・リヴァイヴァル

1830–1880

1830–1880

中世において建築と装飾の主要な様式であったゴシックは、19世紀のイギリスで最も人気のある

復興様式となりました。ヴィクトリア朝の人々は、それを教会に限らず、住宅、鉄道駅、

銀行などあらゆる建物に用いました。

復興様式となりました。ヴィクトリア朝の人々は、それを教会に限らず、住宅、鉄道駅、

銀行などあらゆる建物に用いました。

特徴的なゴシックのモチーフ――尖頭アーチ、尖塔、塔など――は、時計や宝飾品の台座と

いった日用品にも応用されました。デザイナーたちは、中世ステンドグラスや古代の織物に

見られる複雑な装飾に基づいて、豊かな色彩の布地や壁紙の模様を創り出しました。

いった日用品にも応用されました。デザイナーたちは、中世ステンドグラスや古代の織物に

見られる複雑な装飾に基づいて、豊かな色彩の布地や壁紙の模様を創り出しました。

支持者たちにとって、ゴシック様式は道徳的に優れた様式と見なされました。彼らはそれを

「外国的で異教的な古代ギリシャやローマの様式」とは異なり、「英国的かつキリスト教的」

なものと考えたのです。】

「 Gothic Revival(ゴシック・リヴァイヴァル) 」セクション に展示されている

教会祭具・聖具 の一式。

1.聖体顕示用クロス(大十字架)

・左:銀製の大きなクロス(浮彫装飾あり)。典礼用の祭壇十字架。

・中央:金色のクロス。下部は釣鐘形の台座に載っており、典礼で視覚的に荘厳さを演出。

2.聖杯と典礼器具

・中央下:金と銀で装飾された複数の聖杯(chalices)。

・右下:装飾写本や典礼書(豪華な装丁)。

・左下:銀製のピクシス(聖体容器)やカラフなど、聖体やワインを扱う容器。

3.司祭祭服(Chasuble, カズラ)

・右:深紅の織物に金糸刺繍が施されたカズラ(ミサ用外衣)。

・背面には大きな円形の装飾(オーフリース/orfray)に、十字架や聖体シンボルが刺繍されている。

4.背景の装飾布とステンドグラス

・上部:赤地に金糸刺繍の祭壇前掛け(antependium)。

中世風の唐草文様とキリスト教シンボルを表現。

中世風の唐草文様とキリスト教シンボルを表現。

・右端:小さなステンドグラス断片(キリストの受難を描いた場面の一部)。

「 Religion in Britain 1800–1900

In 1800 the Church of England, the established church, exercised a unique power.

Methodists and other Protestants, Roman Catholics, members of other faiths and

atheists all faced obstacles to education, professional advancement and public office.

The Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 is the best known of many changes in the law

that marked the development of religious freedom and led to the gradual removal of

bars to education or employment on religious grounds.Religion in 19th century Britain

was fiercely debated and different groups held stronglyopposing views. All religious

groups were active in building churches, chapels, meetinghouses or synagogues to

provide for the spiritual needs of existing communities and for those that were

developing in the expanding cities. Religion also became the spurto many programmes

of social care for the poor. Religious observance came to be seen as a mark of

respectability and individuals and communities spent large amounts on building and

decorating their places of worship.」

【 イギリスにおける宗教 1800–1900

1800年当時、イングランド国教会(国教会)は特別な権力を有していました。メソジスト派や

その他のプロテスタント、ローマ・カトリック、他宗教の信徒、そして無神論者たちは、

教育・職業的昇進・公職就任において数々の障害に直面していました。1829年のカトリック

解放法(Catholic Emancipation Act)は、宗教的自由の発展を示す数多くの法改正の中でも

最も有名なものであり、宗教を理由とした教育や雇用の制限を徐々に撤廃する道を開きました。

19世紀のイギリスにおいて宗教は激しく論争され、各派は強い対立的見解を持っていました。その他のプロテスタント、ローマ・カトリック、他宗教の信徒、そして無神論者たちは、

教育・職業的昇進・公職就任において数々の障害に直面していました。1829年のカトリック

解放法(Catholic Emancipation Act)は、宗教的自由の発展を示す数多くの法改正の中でも

最も有名なものであり、宗教を理由とした教育や雇用の制限を徐々に撤廃する道を開きました。

すべての宗教団体は、既存の共同体や拡大しつつある都市の新しい共同体の精神的ニーズに

応えるため、教会・礼拝堂・集会所・シナゴーグの建設に力を注ぎました。また宗教は、

貧困層への多くの社会福祉プログラムの原動力にもなりました。宗教的な実践は

「社会的尊敬性の印」とみなされ、個人も共同体も礼拝所の建設や装飾に多額の資金を

投じるようになったのです。】

「 The Church 1840–1900

During the 19th century there was a powerful religious revival in Britain and many

churches were built. As new laws increasingly guaranteed religious freedom, all

Christian denominations took up the challenge of producing new churches for a

population that was growing rapidly, particularly in the cities.

churches were built. As new laws increasingly guaranteed religious freedom, all

Christian denominations took up the challenge of producing new churches for a

population that was growing rapidly, particularly in the cities.

Different groups held strongly opposed views on what was appropriate for the

architecture and decoration of churches. Roman Catholics and some Anglicans saw

rich decoration and furnishings as important elements of worship.Other denominations

favoured plainness both in buildings and services.

Artists, architects, and in particular A.W.N. Pugin designed both churches and theirarchitecture and decoration of churches. Roman Catholics and some Anglicans saw

rich decoration and furnishings as important elements of worship.Other denominations

favoured plainness both in buildings and services.

complete contents. As demand increased, specialist suppliers such as Cox & Sons

(established 1837) and Jones & Willis (established 1855) church furnishings could be

ordered from published catalogues.」

【 教会 1840–1900

19世紀のイギリスでは、力強い宗教復興があり、多くの教会が建設されました。新しい法律が

宗教の自由を次第に保障するようになると、すべてのキリスト教宗派は、急速に増加する人口、

特に都市部における新しい教会建設の課題に取り組みました。

宗教の自由を次第に保障するようになると、すべてのキリスト教宗派は、急速に増加する人口、

特に都市部における新しい教会建設の課題に取り組みました。

異なる宗派は、教会の建築や装飾において何が適切かについて強く対立した意見を持って

いました。ローマ・カトリックや一部の英国国教会信徒は、豊かな装飾や調度品を礼拝の重要な

要素と考えました。一方、他の宗派は建築や礼拝において簡素さを好みました。

芸術家や建築家、とりわけ A.W.N. ピュージン は、教会そのものとその内部装飾のすべてをいました。ローマ・カトリックや一部の英国国教会信徒は、豊かな装飾や調度品を礼拝の重要な

要素と考えました。一方、他の宗派は建築や礼拝において簡素さを好みました。

設計しました。需要が高まるにつれて、Cox & Sons(1837年創業) や Jones & Willis

(1855年創業) などの専門業者が登場し、教会用の家具や調度品を出版されたカタログから

注文できるようになりました。】

・・・ もどる ・・・

・・・ つづく ・・・

お気に入りの記事を「いいね!」で応援しよう

【毎日開催】

15記事にいいね!で1ポイント

10秒滞在

いいね!

--

/

--

© Rakuten Group, Inc.