カテゴリ: エッセイ

■ご先祖探し~その1

■ご先祖探し~その2

■ご先祖探し~その3

■ご先祖探し~その4

■ご先祖探し〜その5(完結篇1)

■ご先祖探し~その6(完結編2)

■ご先祖探し〜その7(完結篇3)

享保年間に徒として彦根藩に召し抱えられ、藩主の家族の世話や賄いなどをしながら、5世代かけて70石とはいえ知行取りとなり、幕末の頃は田舎村の代官を勤めた私の先祖ですが、明治4年に廃藩置県の実施によって生活基盤を失い、他の彦根藩士たちとともに北海道にわたりました。維新軍の功労者たちは、国や自治体の役職につけたのかもしれませんが、(最終的に維新側についたとはいえ)譜代である彦根藩の、まして下級藩士となれば、実態はこのような厳しいものでした。

このあたりのくだりは「 ご先祖探し〜その4 」に詳しく書きましたが、それまでひとつひとつ積み上げてきた実績や信用、人脈などの多くが何の意味もなさなくなってしまうというのは、さぞ辛い経験だったことでしょう。5代目の重右衛門さんがなくなったのは明治5年、53歳の若さだったそうです

さて、このように日本史の表舞台には決して出てない我がご先祖ですが、日本史の重要な局面にはいくつか立ち会っていたようです。

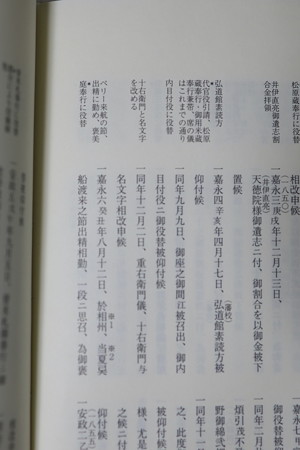

ひとつはこれ。左上の注釈をみると、「ペリー来航の節、出精に勤め、褒美 庭奉行に役替」とあります。なぜペリーがここに出てくるのかというと、彦根藩は弘化4年2月相模国の海岸護衛を命じられ、嘉永6年11月までその任にあったとのことなのです。ペリーが来航したのは、同年6月3日。警備の一員としてとはいえ、ペリーの来航を目の当たりにしていたというのはちょっと驚きです。というか、本人たちもさぞ大騒ぎだったことでしょうねぇ。

もうひとつあります。

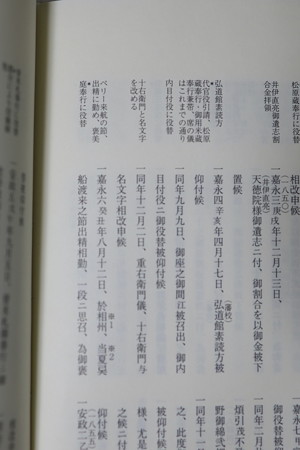

注釈真ん中あたりに、「倅要次、禁門の変の節出張、幕府下賜割合金拝領」とあります。

禁門の変(蛤御門の変)に参加したというのは、「 ご先祖探し〜その4 」にも書きましたが、それと符合します。

>嘉永元年(1848年)出生。16歳の時、初陣で蛤御門の変に参加したものの、幕軍に利なく、槍一>本を担いで逃げ帰ってきたというエピソードがメモに書かれています。

なお、この「倅要次」は別の注釈で、「御舎弟様方御伽頭に雇」という表記も見られます。若い頃、藩主の弟の「御学友」のようなことをしていたのでしょうか?

ちなみにこの方は、私の曽祖父の兄にあたります。前述のとおり、明治5年に父親が亡くなったのを機に、家族とともに北海道の釧路に移住、小学校の教師などを勤め、大正2年に62歳で亡くなったとのことです。

こんな記録もあります。

四代目重右衛門はお城の「中藪口門番頭」を勤めていましたが、配下の筧某への仕置き筋吟味方に不届あり、御叱、差控となった記録が残されています。隠蔽しようとしたのか、部下を庇ったのか知りませんが、いずれにしても配下の不始末の監督不行届ということで、懲戒を食らったようです。こういうところは、なんだか親近感を覚えます。私も会社で同じような痛い思いをしたので…。

さて、そんなこんなで、私の先祖が決してサラブレッドな家柄でないことは、これまでの調査でわかっていましたが、今回、「侍中由緒帳」を読んでみると、あらためて藩士と言っても、末端に近い身分からのスタートだったことが判明しました。

若い頃なら、それを知ってがっかりしていたかもしれません。

しかし、齢60に近づいた今、こうして読むと、全く異なった感慨が湧いてきます。

彼らの日常の断片からは、宮仕えのさまざまな困難や苦労、そして自分たちの持分の中で精一杯頑張って生きていたであろう姿が偲ばれます。歴史上語りつがれるような偉業はなにひとつなし得なかったにしても、そうした幾星霜の苦楽の積み重ねの先に、こうして今の私たちが生きている、その重みを改めて感じずにはいられません。

私自身、大した実績も残せず現役生活を終えようとしていることに、無力感や寂寥感を感じていましたが、くよくよしている場合かという気にもなりますし、まだまだこれからやるべきことやれることはあると自らを鼓舞する気にもなります。

また、どんな形にせよ、文章にして残しておくことで、ご先祖の話などにはとんと興味を示さないウチの子供たちの目にいつか留まることもあるのではないかとも思います。

ご先祖の姿は決して武勇伝に飾られたカッコイイものでありませんが、彼らがその時代時代を一生懸命生きてきた、その重みをわかってもらえるといいなと思います。まあそれは、子供たちがある程度の年齢になってからでないと難しいかもしれませんが。

***********************************

My ancestor was recruited by the Hikone Domain as a foot soldier (to) during the Kyōhō era, serving the domain lord’s family and managing household affairs. Over five generations, though only reaching the status of a stipended retainer with 70 koku, he eventually served as a rural magistrate around the end of the Edo period. However, in 1871 with the abolition of the han system, he lost his livelihood and, along with other Hikone samurai, migrated to Hokkaido. While those who had distinguished themselves with the imperial loyalists may have secured government or local official posts, for a hereditary vassal of Hikone Domain—especially a lower-ranking samurai like my ancestor—the reality was much harsher.

I wrote in detail about this part in "Tracing My Ancestors — Part 4", but it must have been a painful experience to see all the achievements, trust, and connections they had built up over generations suddenly rendered meaningless. The fifth generation Jūemon passed away young at age 53 in 1872 (Meiji 5).

Although my ancestors never appeared on the grand stage of Japanese history, it seems they witnessed several important historical moments firsthand.

Here is one example:

Another example:

In the middle annotation, it says, "Son Yōji dispatched during the Kinmon Incident, awarded a monetary gift by the shogunate." I also wrote about my ancestor’s participation in the Kinmon Incident (the Hamaguri Gate Rebellion) in "Tracing My Ancestors — Part 4".

“The eldest son of Jūemon, named Kihira, was born in 1848. At 16, he fought in the Kinmon Incident but retreated carrying only a spear.”

Although he fled with just a spear, he seems to have been rewarded. The name differs in records because he later changed it from Yōji to Kihira. Another annotation mentions “son Yōji was employed as a playmate to the lord’s younger brothers,” suggesting that in his youth, he might have been a companion or playmate to the domain lord’s siblings. This person was my great-grandfather’s elder brother. After their father died in 1872, he moved with his family to Kushiro, Hokkaido, worked as an elementary school teacher, and died in 1923 at age 62.

Here is another record:

The fourth generation Jūemon served as the gatekeeper at Nakayabu Gate of the castle. However, there is a record of reprimand regarding his supervision of a subordinate named Kakei, who committed some misconduct. Whether he tried to cover it up or protect his subordinate is unclear, but he was disciplined for neglecting proper oversight. I feel a certain closeness to this, having experienced similar troubles at work myself.

So, through my research I had already known my ancestors were far from a blue-blooded family, but reading the “Samurai Retainers’ Genealogical Register” anew confirmed they started from the very bottom ranks of the domain’s retainers. When I was younger, this might have disappointed me. But now, approaching 60, a very different feeling arises.

From the fragments of their daily lives, I sense the various hardships and challenges of serving a feudal lord, and their sincere efforts to live honorably within their limited means. They never achieved heroic deeds recorded in history, but through their centuries of struggle and endurance, here we are today. This weight of legacy moves me deeply.

I myself have felt powerless and lonely nearing the end of my own career without great accomplishments, but dwelling on that won’t help. I am motivated to keep moving forward, knowing there is still much to do and achieve.

Moreover, by putting these stories into writing, perhaps someday my children—who show little interest in our family history—might come across them. My ancestors’ lives were not adorned with tales of valor, but I hope my children will understand the weight of their sincere lives lived through difficult times. Though, that may be something only possible when they are older.

I have grown sentimental here at the end. For now, I will conclude my “Tracing My Ancestors” series, but should new stories arise, I might resume someday.

■ご先祖探し~その2

■ご先祖探し~その3

■ご先祖探し~その4

■ご先祖探し〜その5(完結篇1)

■ご先祖探し~その6(完結編2)

■ご先祖探し〜その7(完結篇3)

享保年間に徒として彦根藩に召し抱えられ、藩主の家族の世話や賄いなどをしながら、5世代かけて70石とはいえ知行取りとなり、幕末の頃は田舎村の代官を勤めた私の先祖ですが、明治4年に廃藩置県の実施によって生活基盤を失い、他の彦根藩士たちとともに北海道にわたりました。維新軍の功労者たちは、国や自治体の役職につけたのかもしれませんが、(最終的に維新側についたとはいえ)譜代である彦根藩の、まして下級藩士となれば、実態はこのような厳しいものでした。

このあたりのくだりは「 ご先祖探し〜その4 」に詳しく書きましたが、それまでひとつひとつ積み上げてきた実績や信用、人脈などの多くが何の意味もなさなくなってしまうというのは、さぞ辛い経験だったことでしょう。5代目の重右衛門さんがなくなったのは明治5年、53歳の若さだったそうです

さて、このように日本史の表舞台には決して出てない我がご先祖ですが、日本史の重要な局面にはいくつか立ち会っていたようです。

ひとつはこれ。左上の注釈をみると、「ペリー来航の節、出精に勤め、褒美 庭奉行に役替」とあります。なぜペリーがここに出てくるのかというと、彦根藩は弘化4年2月相模国の海岸護衛を命じられ、嘉永6年11月までその任にあったとのことなのです。ペリーが来航したのは、同年6月3日。警備の一員としてとはいえ、ペリーの来航を目の当たりにしていたというのはちょっと驚きです。というか、本人たちもさぞ大騒ぎだったことでしょうねぇ。

もうひとつあります。

注釈真ん中あたりに、「倅要次、禁門の変の節出張、幕府下賜割合金拝領」とあります。

禁門の変(蛤御門の変)に参加したというのは、「 ご先祖探し〜その4 」にも書きましたが、それと符合します。

>嘉永元年(1848年)出生。16歳の時、初陣で蛤御門の変に参加したものの、幕軍に利なく、槍一>本を担いで逃げ帰ってきたというエピソードがメモに書かれています。

なお、この「倅要次」は別の注釈で、「御舎弟様方御伽頭に雇」という表記も見られます。若い頃、藩主の弟の「御学友」のようなことをしていたのでしょうか?

ちなみにこの方は、私の曽祖父の兄にあたります。前述のとおり、明治5年に父親が亡くなったのを機に、家族とともに北海道の釧路に移住、小学校の教師などを勤め、大正2年に62歳で亡くなったとのことです。

こんな記録もあります。

四代目重右衛門はお城の「中藪口門番頭」を勤めていましたが、配下の筧某への仕置き筋吟味方に不届あり、御叱、差控となった記録が残されています。隠蔽しようとしたのか、部下を庇ったのか知りませんが、いずれにしても配下の不始末の監督不行届ということで、懲戒を食らったようです。こういうところは、なんだか親近感を覚えます。私も会社で同じような痛い思いをしたので…。

さて、そんなこんなで、私の先祖が決してサラブレッドな家柄でないことは、これまでの調査でわかっていましたが、今回、「侍中由緒帳」を読んでみると、あらためて藩士と言っても、末端に近い身分からのスタートだったことが判明しました。

若い頃なら、それを知ってがっかりしていたかもしれません。

しかし、齢60に近づいた今、こうして読むと、全く異なった感慨が湧いてきます。

彼らの日常の断片からは、宮仕えのさまざまな困難や苦労、そして自分たちの持分の中で精一杯頑張って生きていたであろう姿が偲ばれます。歴史上語りつがれるような偉業はなにひとつなし得なかったにしても、そうした幾星霜の苦楽の積み重ねの先に、こうして今の私たちが生きている、その重みを改めて感じずにはいられません。

私自身、大した実績も残せず現役生活を終えようとしていることに、無力感や寂寥感を感じていましたが、くよくよしている場合かという気にもなりますし、まだまだこれからやるべきことやれることはあると自らを鼓舞する気にもなります。

また、どんな形にせよ、文章にして残しておくことで、ご先祖の話などにはとんと興味を示さないウチの子供たちの目にいつか留まることもあるのではないかとも思います。

ご先祖の姿は決して武勇伝に飾られたカッコイイものでありませんが、彼らがその時代時代を一生懸命生きてきた、その重みをわかってもらえるといいなと思います。まあそれは、子供たちがある程度の年齢になってからでないと難しいかもしれませんが。

***********************************

My ancestor was recruited by the Hikone Domain as a foot soldier (to) during the Kyōhō era, serving the domain lord’s family and managing household affairs. Over five generations, though only reaching the status of a stipended retainer with 70 koku, he eventually served as a rural magistrate around the end of the Edo period. However, in 1871 with the abolition of the han system, he lost his livelihood and, along with other Hikone samurai, migrated to Hokkaido. While those who had distinguished themselves with the imperial loyalists may have secured government or local official posts, for a hereditary vassal of Hikone Domain—especially a lower-ranking samurai like my ancestor—the reality was much harsher.

I wrote in detail about this part in "Tracing My Ancestors — Part 4", but it must have been a painful experience to see all the achievements, trust, and connections they had built up over generations suddenly rendered meaningless. The fifth generation Jūemon passed away young at age 53 in 1872 (Meiji 5).

Although my ancestors never appeared on the grand stage of Japanese history, it seems they witnessed several important historical moments firsthand.

Here is one example:

Another example:

In the middle annotation, it says, "Son Yōji dispatched during the Kinmon Incident, awarded a monetary gift by the shogunate." I also wrote about my ancestor’s participation in the Kinmon Incident (the Hamaguri Gate Rebellion) in "Tracing My Ancestors — Part 4".

“The eldest son of Jūemon, named Kihira, was born in 1848. At 16, he fought in the Kinmon Incident but retreated carrying only a spear.”

Although he fled with just a spear, he seems to have been rewarded. The name differs in records because he later changed it from Yōji to Kihira. Another annotation mentions “son Yōji was employed as a playmate to the lord’s younger brothers,” suggesting that in his youth, he might have been a companion or playmate to the domain lord’s siblings. This person was my great-grandfather’s elder brother. After their father died in 1872, he moved with his family to Kushiro, Hokkaido, worked as an elementary school teacher, and died in 1923 at age 62.

Here is another record:

The fourth generation Jūemon served as the gatekeeper at Nakayabu Gate of the castle. However, there is a record of reprimand regarding his supervision of a subordinate named Kakei, who committed some misconduct. Whether he tried to cover it up or protect his subordinate is unclear, but he was disciplined for neglecting proper oversight. I feel a certain closeness to this, having experienced similar troubles at work myself.

So, through my research I had already known my ancestors were far from a blue-blooded family, but reading the “Samurai Retainers’ Genealogical Register” anew confirmed they started from the very bottom ranks of the domain’s retainers. When I was younger, this might have disappointed me. But now, approaching 60, a very different feeling arises.

From the fragments of their daily lives, I sense the various hardships and challenges of serving a feudal lord, and their sincere efforts to live honorably within their limited means. They never achieved heroic deeds recorded in history, but through their centuries of struggle and endurance, here we are today. This weight of legacy moves me deeply.

I myself have felt powerless and lonely nearing the end of my own career without great accomplishments, but dwelling on that won’t help. I am motivated to keep moving forward, knowing there is still much to do and achieve.

Moreover, by putting these stories into writing, perhaps someday my children—who show little interest in our family history—might come across them. My ancestors’ lives were not adorned with tales of valor, but I hope my children will understand the weight of their sincere lives lived through difficult times. Though, that may be something only possible when they are older.

I have grown sentimental here at the end. For now, I will conclude my “Tracing My Ancestors” series, but should new stories arise, I might resume someday.

お気に入りの記事を「いいね!」で応援しよう

[エッセイ] カテゴリの最新記事

-

「ABCブック」とタイトルを思い出せない昔… 2025年08月15日

-

ショック!「暇人速報」閉鎖か?【まとめ… 2025年08月07日

-

「テル子女神像」はなくなりました 2025年04月21日

【毎日開催】

15記事にいいね!で1ポイント

10秒滞在

いいね!

--

/

--

PR

X

Comments

shuz1127

@ Re[1]:モーリス・ユトリロ展@SOMPO美術館~その1 Maurice Utrillo Exhibition at the SOMPO Museum — Part 1(11/10)

Henryさん おお、西山美術館に行かれたの…

Henry@ Re:モーリス・ユトリロ展@SOMPO美術館~その1 Maurice Utrillo Exhibition at the SOMPO Museum — Part 1(11/10)

西山美術館、メルカリで無料招待券をお安…

shuz1127

@ Re[1]:ほどよく均整の取れたベリーA~マスカットベリーA2023(白百合醸造) Well-Balanced Berry A – Muscat Bailey A 2023 (Shirayuri Winery)(10/10)

noir-funさんへ 熊本ワインファーム、例…

noir-fun

@ Re:ほどよく均整の取れたベリーA~マスカットベリーA2023(白百合醸造) Well-Balanced Berry A – Muscat Bailey A 2023 (Shirayuri Winery)(10/10)

機会があれば是非、熊本ワインファームの…

shuz@ Re[1]:悪くはないのだけど…エラスリス MAX・カベルネソーヴィニヨン2020 “Not bad, but not quite…” — Errazuriz MAX Cabernet Sauvignon 2020(09/24)

noir-funさん ご無沙汰していますが、お…

Category

カテゴリ未分類

(10)お知らせ・リンク集

(29)ワイン新着情報

(515)ワインコラム

(343)ワインコラム2(話飲徒然草拾遺集)

(75)ワインコラム3(RWGコラム拾遺集)

(28)都内近郊散策

(281)こんな店に行った

(326)B級グルメ・カフェ

(248)健康

(219)エッセイ

(76)ひとりごと・備忘録

(541)カミサン推薦ネタ

(28)語学・資格・学び直し

(95)山歩き・ハイキング

(123)アクアリウム・ガーデニング

(339)育児・教育

(88)PCネット時計カメラ

(129)音楽・オーディオ

(70)リフォーム引越し

(50)こんなワイン買った

(129)ボルドー

(99)ブルゴーニュ・ジュブレシャンベルタン

(90)ブルゴーニュ・モレサンドニ

(40)ブルゴーニュ・シャンボールミュジニー

(45)ブルゴーニュ・ヴォーヌロマネ・ヴジョ

(56)ブルゴーニュ・NSG

(58)ブルゴーニュ・その他コートドニュイ

(63)ブルゴーニュ・コルトン・ポマール・ヴォルネイ

(30)ブルゴーニュ・ボーヌ周辺

(56)ブル・ピュリニー・シャサーニュ・ムルソー

(21)ブルゴーニュ・その他コートドボーヌ

(27)ブルゴーニュ・裾モノイッキ飲み!

(221)ブルゴーニュ・その他地域

(37)ボジョレー再発見プロジェクト

(32)シャンパーニュ

(195)ロワール・アルザス・ローヌ

(54)その他フランス

(16)イタリア

(80)スペイン・ポルトガル

(37)ニュージーランド・オーストラリア

(49)USA

(40)安泡道場(シャンパーニュ以外)

(37)その他地域・甘口など

(43)日本ワイン

(64)ワイン会・有料試飲

(173) セシル・トランブレ…

New!

mache2007さん

New!

mache2007さん

【wine】アルザスシ… ささだあきらさん

ささだあきらさん

貝殻亭でランチ zzz.santaさん

zzz.santaさん

EF210-328 EF510-3… musigny0209さん

グラムノン yonemuさん

yonemuさん

ジャン・ルイ・シャ… hirozeauxさん

hirozeauxさん

実南 月一会 ミユウミリウさん

ミユウミリウさん

ワイン&ジョギング … Char@diaryさん

道草日記 旅・釣… 道草.さん

鴨がワインしょって… うまいーちさん

New!

mache2007さん

New!

mache2007さん【wine】アルザスシ…

ささだあきらさん

ささだあきらさん貝殻亭でランチ

zzz.santaさん

zzz.santaさんEF210-328 EF510-3… musigny0209さん

グラムノン

yonemuさん

yonemuさんジャン・ルイ・シャ…

hirozeauxさん

hirozeauxさん実南 月一会

ミユウミリウさん

ミユウミリウさんワイン&ジョギング … Char@diaryさん

道草日記 旅・釣… 道草.さん

鴨がワインしょって… うまいーちさん

Keyword Search

▼キーワード検索

Calendar

© Rakuten Group, Inc.